There are bands who provide their fans with the satisfaction of good music, but perhaps little else. There are bands who turn a witty phrase, or move a mosh pit, and many are here today and gone tomorrow. Once in a while comes a band that does not only provide unforgettable songs, but bolsters our spirits and gives us a soundtrack to the struggle and spirit of our lives.

Primordial, from Dublin, Ireland, falls into this latter category for the vast majority of its fans. This autumn, they released their tenth studio album, entitled How It Ends. A pièce de résistance and easily one of the best albums of 2023, Vocalist Alan Averill was kind enough to sit down to shed some light on the philosophies behind the latest Primordial album. Join us as we go in-depth on what drives the man behind the microphone.

Cryptic Rock – Primordial can look back across a career which spans more than 30 years. Most bands with that sort of lineage, including most of the ones we grew up with, tended to make their classic material early in their careers. In doing so, they were left with no other choice but to chase that standard of quality forever after. Whether it’s the mournful riffs of Ciáran MacUiliam, or your own strengthening voice and ever-widening vocal range, everything with Primordial seems to be growing stronger as the years pass. The older you guys get, the stronger the band sounds.

Do you think this has to do with the fact that you don’t do Primordial for a living, or that pressure from the outside world maybe isn’t as great as when bands were on record labels that constantly pressured them to put out new material?

Alan Averill – Don’t forget, when bands like Entombed and Dismember made their debut albums, they weren’t making a living, or professional, either. I think there’s a combination of things. I think one is the fact that, especially for aggressive music, because it’s about the impetuosity and recklessness of youth and it’s trying to capture the lightning in a bottle you had of all that reckless energy when you were 18 to 20, when you’re 50 it’s kind of very difficult. And because we never really set out our stall like that, Primordial was always a little bit different.

And we also weren’t orthodox Black Metal, which would’ve ended up pigeonholing us and disappointing maybe people in the long run because you either change, or move away, or do something different five, six, seven, eight albums later. We never really did that. I mean there’s songs like “All Against All” from the new album, that the riffs could be on the first album. And it’s not a big deal to us.

We sort of slipped underneath the radar for the first album or two. We had a smaller fan base, we didn’t explode out of the traps a la Left Hand Path, or whatever, first day aside. That wasn’t really, or for other Black Metal albums at the time. We weren’t really that band, which we grew quite slowly. But also sort of like plowing our own small furrow. And because our musical style wasn’t linked to aggression and testosterone, and we didn’t lay out our stall to only then retreat from the trenches, we were able to take a slightly different path. And I think now, yeah, you’re right, it stands to us that the most popular and the strongest albums are the last few. And of course I’ll meet somebody who goes, “Oh, I only like Journey’s End.” “Yeah, that’s okay.” Or Spirit the Earth Aflame.

I think sometimes that depends on what age you are, but I think kind of inarguably, Primordial’s richer vein of certainly the most popular albums are the last four or five, six. You know? And so, I’m very happy to not be tethered to having to play the debut album and that nobody cares about anything we’ve made for the last 10 years. So yeah, you’re right, we did it the other way around.

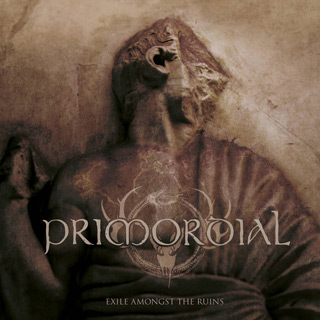

Cryptic Rock – That is so much better than perpetually chasing the magic of some distant early work. Examining the overall mood on How It Ends, compared with 2018’s Exile Amongst the Ruins, there is a noticeable shift. Even down to the album cover, where How It Ends features this dire man with pistol clutched in hand; Exile Amongst the Ruins had more wistfulness and a contemplative vibe to the lyrics, where with this album there appears to be a lot more of a call to arms going on.

A boiling rage is felt in places, with common men left to face insurmountable odds. The authoritarian panic, the government overreach, and the resulting attack on the music industry – all contributing to the feeling of being one small pawn against a grinding inevitable collapse. How much of the lyrical bent of How It Ends stems in some small part from what we all just went through in the past few years?

Alan Averill – Yeah, I mean, I think so. I didn’t want to make a pandemic lockdown “isn’t this terrible” kind of album. That’s not really my style. Of course, the pandemic and lockdown especially influenced the atmosphere of the album. And without a doubt we can see in society a lurch towards authoritarianism. I think what I wanted to do was, if you take an album like To the Nameless Dead, which is about the establishment of nations, the movement of borders, the movement of peoples, I was always obsessed with maps and cartography. And if you tie it with the special edition To the Nameless Dead, there’s all these old maps in it. And I was obsessed with what happened to this, what happened to the Limburgeans, what happened to all these Roman city-states? What happened to peoples that were eclipsed?

Well, this album is kind of, if you can imagine almost like the doomed resistance, the doomed historical, romantic, resistance, within all of these member states who resisted authority, who resisted colonialism, who resisted empire, who resisted, I suppose, authoritarian states throughout the last, I kind of set it maybe from the end of the 19th century up until now, so it would have echoes to the modern age. But it’s not not really about being Irish or those elements of the Irish Civil War in it. It could echo the Haitian Revolution. It could echo revolutionary states or revolutionary figures throughout the world. There’s a kind of doomed romance to the album.

The idea is that “liberty” is the most important word in any language, and that’s what the entire basis of the strife within our civilization is about is the pursuit of liberty either for the occupied nation state or the peoples within it resisting an authoritarian theocracy or a one-party state or a political ideology that oppresses the general people. It’s like a sort of outlaw album, like a rebel album, almost like, I’m not going to go as far as say like a working-class album, but it kind of is. It’s kind of got a sort of defiant “fuck you-ness” to the tone of it in a sense, “We’ll go down swinging, we’ll go down fighting,” but it asks a lot of questions to people. And one of those is, “Democracy is not the default setting of society.” And democracy is a thing that, like freedom of speech, needs to be tended to. And it feels like we’ve left it unattended for a long time, and that a lot of people were very happy to hand over their freedoms.

And I think that the implications of what happened during the last four or five years are, well, they are being felt now in a lawless world that lurches towards embracing a war-like state. And nobody can tell me that isn’t linked to some of the draconian inflationary financial measures of the last couple of years amongst other things, and also just disaster capitalism amongst other things. So it feels like we as a society are at the end of a period of reasonable upward mobility and stability, and now we’re being pushed towards what one could call a sort of element of modern day digital feudalism, perhaps. And so the question is for me, in my own small way through the lyrics, like, “How did it feel when they called your name for the last time or made you stand in line” – and so that’s the general impulse and because I believe it’s coming.

What remains to be seen, of course, we’re all privy to the excesses of our own algorithm. So, I’m not conspiracy-theory-mad or anything like this, but if somebody wants to argue with me about some of these things and whether democracy is the default setting of society, Western society, or all societies, it’s not the norm, it never has been. And if you want examples of the lurched war’s authoritarianism, I can give you 50 off the top of my head from the last however many, whatever country you want.

Listen to my podcast called, “Your Favorite 1970s Dictators.” And then you realize, “Oh, Salazar in Portugal, Franco in Spain.” This was the 1970s and onwards, and across the African continent. So I think we in the West have been, while we war with each other over classic divide and conquer measures, promulgated and propagated by institutions of state and governance who benefit from us tearing strips off each other, I think that we lurch towards a more authoritarian state. And so, the album’s not a modern-day historical kind of Thrash Metal ‘say what you see’ lyric, not really my style.

Cryptic Rock – The themes on How It Ends absolutely resonate with the world we find ourselves in today, while not marrying themselves to any particular place or event.

Alan Averill – Yeah, I mean say for example, you’ve got a song about Joseph Plunkett, who was a famous Irish nationalist, but a poet, kind of a romantic guy. And there’s a very famous Irish traditional song called “Grace,” because the night before he was shot by the English, he married his childhood sweetheart Grace, and that was the night before he was shot. If you go and check out the song “Grace,” it’s very famous in Ireland, and sort of heart-wrenching about their one night in prison together. But I examined the life of Joseph Plunkett and this young romantic nationalistic man who kind of knew what was on the cards for him. And so I took a part of his poem and put it in at the end of one of the songs.

It is a kind of little moment of living history, but also the question presented, who are the Joseph Plunkett’s that you have in your country or any country? We wanted to take a look at these sometimes doomed romantic figures. And so there is a doomed romance to the album. It’s not exactly political, you know? It can be understood from all sides. As I say, it’s kind of an album sort of like working class regular folk resisting against the yoke of authority kind of album.

Cryptic Rock – There is a lot of emotion on the album, that’s for sure. The title-track has already elicited some tears from this particular scribe. Clearly, composition is serious business for Primordial. When you sat down to write this music, did you carry any prior albums in your heads that you were feeling the echoes of? Or do you think each writing process, you try to cut yourself off from prior albums? How It Ends features some lovely callbacks to Spirit the Earth Aflame, Redemption at the Puritan’s Hand. Especially in the beautiful traditional song “Call to Cernunnos.” One could close one’s eyes and it’s as if “The Cruel Sea” got transformed into more of a rocker.

Alan Averill – I hear you, yeah. I mean, we don’t really pay that too much consideration. We kind of don’t care. So, you have a song like “All Against All”, which is like this swinging very simple, simplistic, almost Black Metal song. I said, “It could be on the first album.” Everybody goes, “Yeah, but we don’t have to progress from the first album. It doesn’t bother me. I liked the first album.” A song like “The Fires,” no big deal for me. We’re not really worried about progressing or evolving, even though we do, we don’t really think about it too much. And so I like callback bits. Ciáran doesn’t like them, but there’s often lyrical little elements where I call back to a song. And I try to sneak them by him. But sometimes there’s a riff and you go, “That sounds a bit like Children of the Harvest.” Everybody goes, “Well okay, but that’s our style.”

Like I said, we never had a weird electronic moment. We never had a remix album, a boring acoustic album. We just plowed our own furrow, our own niche, and we sort of never really second-guessed it too much. But a lot of Primordial, it’s kind of instinctual. You don’t second guess yourself and you think, “Oh, this sounds like it has meaning and purpose and energy and vitality, and does the riff sound like something maybe from another album?” Possibly. But it’s not an exact science and we try to be as instinctual as possible. We don’t spend too long worrying about the finer details.

Cryptic Rock – Primordial is a band that’s more about feeling than about striving for some kind of innovation, or technical supremacy.

Alan Averill – I will say if you take a song like “Sunken Lungs” from the previous album Exile Amongst The Ruins, you’ll find a very complicated time signature and a very complicated rhythm. And it’s quite complicated in a much more organic way to, like, then Tech Death, sweep things. And man the chords are strange, the tuning’s strange. If you want to look, it’s there to find some elements of complicated musicianship. Then again, sometimes a song just sounds like bare riffs, and that’s a cool song. And “Sunken Lungs” is a fucking hard song to sing.

Cryptic Rock – It is without a doubt one of the best songs Primordial has written. Returning to How It Ends, particularly the song “Nothing New Under the Sun” and the line “How we feared God, held a flame into the void and snuffed out the Creator, how we became death, the destroyer of worlds.” So obviously in that line, it’s loaded with the idea that our inquisitiveness about God, about cheating death in order to figure out all of creation, combined with a direct reference to nuclear war, which is our highest technological reach of destruction.

And it was almost like a duality, like maybe were you thinking all of that human inquisitiveness and quenchless desire to cheat death through maximum power, do you think that whether you’re pursuing that theologically, or technologically, it might just lead to the same path of human destruction, or arrogance? Sometimes the pursuit of science, or the discussion around it, can be cloaked in such religious language. For example, how the adage “follow the science” became a mantra not unlike fundamentalist religious dogma.

Alan Averill – Well, I wrote the song before the movie Oppenheimer, by the way. I was always fascinated with him, and I’d read some stuff about him. And I think what I’m trying to say is also in the title, that splitting the atom, so to speak, we did that with everything available to us under the sun. And under the sun as well were all our structures of religious belief, all the things that we tried to create to make sense of death. And in one moment we created something that could literally extinguish all life on earth. And so yes, it’s the kind of stark idea that even somebody like Oppenheimer invoked with that sentence, “I have become death, destroyer of worlds,” he’s taken that from some, was it the Diwali or something? I can’t remember some religious books from the Far East. And even in describing what is this sort of technological pursuit of a scientific pursuit, he’s using religious imagery or religious words, a religious text.

And I suppose I kind of had always wanted to write something about that ability that we have. It’s similar to what you hear at the moment, religious talk about climate change and about carbon, and we are all, the world is made of carbon. Like, it’s kryptonite or something. And you see how quickly our language can evolve into almost like a religious mantra that at the heart of it, some sort of scientific inquiry is still bound by lots of the same language. I suppose what I was trying to say is that we somehow created from everything we had under the sun, the ability to block out the sun.

Cryptic Rock – That is quite a poignant perspective. Speaking of the connection between religion and philosophy in terms of lyrics, I have always felt there was a connection between bands of a certain vintage coming from England and Ireland, such as yourselves, and particularly My Dying Bride and Anathema. Aaron Stainthorpe and the Cavanagh brothers, and yourself, appear to have dealt in your art with your relationship to the Christian culture which pervades your collective upbringing. I don’t think guys from the Scandinavian bands, despite all their odes to blasphemy, they don’t grow up under the same thumb of religious presence, influence, and instruction.

Alan Averill – Well, don’t forget, Scandinavians are Protestant or Presbyterian or whatever you want to say, and by and large have had a very different run in the 20th century than most countries in Europe. If you look at a country like Sweden, it never had communism or fascism connected to any religious institution. Whereas you look at Italy or something like that, or Spain, or Ireland, the complicated histories they had. I think one thing I might share with Aaron is that there’s a song in the new album called “Death Holy Death,” and this is kind of a song about the beauty or iconography of religious sacrament or something like this.

I was in Sicily and watching a religious parade and they were carrying all these huge wooden floats with virginal characters on them. And the walls of the old town were draped in all these old flags. And it’s a kind of fascinating religious pageantry. You’re an observer in this ancient custom. And I think maybe Aaron touches on some of that religious imagery as well. Anathema are from Liverpool, and I mean these are all people that we know and stuff as well. They’re all Irish families, the Cavanaghs, so I guess there’s a sort of element of Catholicism in their upbringing as well that I’m not sure My Dying Bride necessarily has. But there’s certainly an incredible deep religious history to the areas that they grew up in. If you go back 600 years, go back to Yorkshire and the Plantagenets or the Jacobites or whatever, this I think echoes through some of the music.

In Ireland it’s a little bit different. There are some songs I’ve written, “Ghosts of the Charnel House,” which sort of deal with Catholic abuse and try to make it a very visual song about the sacristy or the sort of barbaric elements, the treatment of people at the hands of the church after the state handed it over to them after the famine. But I think you’re always trying to do it with a certain amount of visualization and sort of trying to encapsulate it in something poetic, these grim things.

But yeah, I mean there’s certainly, if you were to sit in a room full of MDB artists, you’ll hear the same cultural references, same sense of humor, the same dark sense of humor, the same cultural things that you grew up with, same elements from the working-class societies and their relationship to religion and faith through your grandparents. And yeah, we’re intrinsically linked even though a lot of things are different. But Primordial has of course this deep-weighted sense of melancholy that’s part of our relationship to the dark nature of Irish history. Some anger, some sadness, some melancholy, some examinations of the terrible poverty or the terrible trials and struggles and tribulations of the people.

If somehow I’m able to raise a voice, sometimes I do that, I try to just raise a voice to these elements of this history, to speak through a song in my own small way. So you try to make sense of this very complicated, dark history. Maybe that’s what you hear. I don’t know. I don’t know if that’s possible for Swedes maybe, who never underwent the “isms” of the 20th century or First or Second World War on their lands or religious oppression like Ireland or Spain or Italy or Romania.

Cryptic Rock – That is an excellent insight into the underlying cultural factors present in Primordial’s music. Returning to the music itself, it seems that heavy metal’s different subgenres had far more ardent defenders than perhaps exists today in our saturated internet age. Subgenre no longer appears to be the dividing line, whereas now it seems like production divides the masses from the underground connoisseur. Ultra-modern, ultra-slick studio production turns a lot of the more discerning fans off. Do you think that this is the new dividing line in the early 2020’s?

Alan Averill – I think it is a dividing line, but I also think the existence of sub-genres is also still a dividing line. There are people who want black metal to have things attached to suffixes to it. They want shoegaze Black Metal, they want post-black metal, they want anarcho Black Metal, they want deviant Black Metal, they want whatever, pagan Black Metal. And there’s of course tons of divisions there were never the twain shall meet. Sometimes if you’re like this, you’ve decided you don’t like that. But it’s true. I mean, I’ve had discussions with kids at thrash shows and they’ve gone, “Oh, I don’t like anything by Exodus or Kreator from the ’80s, their sound is shit.” And I’m like, “You think that, let’s say Tempo of the Damned,” well, Tempo of the Damned is a record I really like a lot actually, so what’s the one I like after that? And I don’t know.

Cryptic Rock – What about Shovel Headed Kill Machine?

Alan Averill – Yes “Do you really think Shovel Headed Kill Machine sounds better than Bonded by Blood?” I’m like, “Never in a million years.” But they grew up in different times, they’re listening to music in a different way, if you’re listening digital through digital headphones. But I agree with you, the snappy drums and the whatever, you’re saying with Kreator, a kid who really loves Hordes of Chaos, maybe listens to Endless Pain and goes, “What the fuck is going on?”

But I only had the same conversation with somebody last weekend and they were going, “Yeah, I love those old bands and records, but they sound like shit.” I’m like, “No, they sound amazing.” Because what people are missing in this kind of translation is character and intent and the impetuosity of youth, and the tones and the playing and the fact that not everything is supposed to be quantized and moved.

And I mean, look, I don’t really know anything about Tech-Death, I prefer the Misfits and Venom. I mean, I love Gorguts. I don’t know if that counts. But I agree with you. I like old-school sounds, I like the old-school drum kits. I like old-school tones and everything. So yeah, it’s not for me. But every now and again something comes along and I’ll go, “All right,” you know. It depends. I think the genre thing is probably still a dividing line for lots of people. There’s certain things they just decided they won’t listen to because of the noise that surrounds whatever genre. I don’t know.

Cryptic Rock – Those are excellent points. Primordial has certainly had what I would call a “production consistency” over the years, because you can really feel Spirit the Earth Aflame when you listen to How It Ends, and you can feel Redemption at the Puritan’s Hand or even the first album Imrama, but in a way that’s familiar, like hanging out with an old friend who is familiar, has a familiar way of speaking to you, but they’re discussing something entirely new in that familiar voice.

Alan Averill – Well, I don’t think any of the albums have perfect sound or what I always envisaged, because I don’t want them to be perfect. I think flaws give you character. And I like the fact that sometimes there’s, you know, like The Gathering Wilderness was not our intention to sound like that. The mix was kind of a disaster zone at the time. A lot of problems, lots of things happening. But in the end, people love it and it’s got a strange claustrophobic feel that’s not what we imagined.

But you accept these things with grace and try to understand that, yeah, like I said, flaws give character, and I would rather have a record with massive character that was technically a three-out-of-10 production job, than seven-out-of-10. Forget it, either give me something amazing like Queens of the Stone Age, which sounds incredible, or give me something grim as fuck. Nothing more boring than, “Yeah, it’s okay.”

No comment