There is an old saying that goes, “If you are not making progress, you are standing still.” For legendary English guitarist Steve Hackett, that concept has defined his prominent career in which he has tested the waters in Pop, Rock, Jazz, Blues, Classical and everything in between. A key component to the success of the Progressive Rock band Genesis, Hackett’s guitar styling helped build the foundation of the band’s storied career over the course of the six studio albums he contributed to. Parting ways with the band back in 1977, Hackett devoted his talents to an array of musical themes with a solo career spanning over three decades and a slew of albums to his name. Now exploring a new concept in 2015, he released his latest masterpiece, Wolflight, released in Europe on March 30, 2015 and in the US on April 7, 2015. Recently, we sat down with the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer for a introspective look into his past with Genesis, his enthusiasm for crafting music, inspirations, and much more.

CrypticRock.com – You have been involved in music for nearly five decades now. In that time, you have celebrated a strong solo career as well as being a member of Genesis for six studio albums and three live albums. First, tell us what was it like when you first joined up with Genesis?

Steve Hackett – Well, I was much younger then and I think my priorities were slightly different. Although I advertised myself as a guitarist and writer, it was a little bit like when you decide from one day to the next that is what you’re going to be. The most important thing that a master chef can do is decide one day he’s going to become a master chef. He hasn’t got any idea about how to cook a meal, where to start or even how to peel a potato, but with just a little bit of chutzpah and a dream… It seems to me that all things are possible. I set my sights in a different way. I wanted to work with a band that had a mellotron. I wanted to be able to work with a band that would be able to sound like an orchestra at the drop of a hat or possibly like a facsimile of one, and when I first joined Genesis, the keyboard arsenal needed expanding. I managed to get my own way despite some opposition. Therefore, within the first six months, we acquired a mellotron and indeed we did start sounding a little bit like how I thought the band could sound; that four or five guys could indeed sound like an orchestra and a choir.

- Charisma

- Charisma

CrypticRock.com – In your time with Genesis you indeed had a strong influence in the band’s direction. It was in 1977 when you decided to depart from Genesis to pursue your solo career. Were you at all apprehensive about leaving the band at the time?

Steve Hackett – Well, I was really tired of band politics by then. I felt that the politics were also standing in the way of a very good idea. I think so many good ideas were rejected by the band. I’m not just talking about my own, but several ideas by other people. I felt that, in a way, one’s got to serve the best interest of the music and ultimately your allegiance has to be to music and not any one or a bunch of individuals. Even though they might be the greatest band in the world, at the end of the day if it is standing in the way of the music, you’ve got to nail your colors to the mast. Yes, of course I was apprehensive. I think the euphoria lasted probably through morning and then by the time I had lunch, I had quite some way to go to catch up with the magnificent brainchild that we’d all given birth to. Genesis was everyone’s brainchild. Some people screwed on the arms and legs and other people pulled them off at times, but nonetheless it was a high achieving band and I was very proud of it. Although there is that thing, “You can’t keep a good Hackett down.” Certain things will come out and material is bursting to be done, but you know that the band was not going to do it. I was not prepared to have still born brainchildren and that’s it at the end of the day. Of course this was many, many years later. I could’ve become father to the young guy that I was twice over since. It is a very long time ago.

- Charisma

- Charisma

CrypticRock.com – Yes, it has been a long time now. The decision certainly worked out for you, as you have had a very great career solo releasing many records. You have also reunited with Genesis on numerous occasions through the years. All musicians want to have the ability to grow and explore. In your solo career you have explored a broad range of elements, from Progressive Rock to Classic guitar to Pop as well. What inspired this exploration in sound for you?

Steve Hackett – Well, my first inspiration as a very young child was my father, who was gifted enough to be able to play a number of different musical instruments. He was a very talented man. He was also a very sweet, polite man and I learned harmonica from him. I was trying to copy him from the age of two onward. I was trying to play tunes on the harmonica. That was my first influence. Then, over the years, I realized that I was interested in lots of different kinds of music and they weren’t all coming from the same school. The Rock and Pop music that I thought were absolute masterpieces that were appearing in the late 1950’s and the early 1960’s that were, in hindsight, very simple ideas, but they were also very well done by great singers, usually from America. I’m thinking of the Everly Brothers, Roy Orbison, Elvis Presley, and many of the great singers that were over there.

At the same time that I listened to that, I became aware of Classical music; Bach, Tchaikovsky, and Chopin. I thought that perhaps as an untrained musician, I would probably end up doing something closer to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, then I was exploring anything that Bach, Tchaikovsky, and Chopin had done. I then discovered that people were starting to fuse the two elements, the African-American influence and the European chord exploration. I think that Progressive rock was born from those very disparate and separate schools of thought. It was kind of an Anglo-American, or even a Euro-American school that was coming out of those very separate styles.

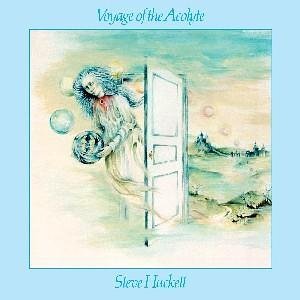

- Chrysalis Records

- Chrysalis Records

CrypticRock.com – Those styles bleed through on the records you have put out as well.

Steve Hackett – Well, I think that when I was doing my second solo record, which was called Please Don’t Touch (1978), I remember the record company head, Tony Stratton-Smith, who was a very perceptive man said, “Its diversity is its strength and its weakness.” I was aware of what he was saying. I had many different performers on it and many different styles of music, and it was to become a style in itself. Sometimes I was to pay heavily and dearly for that. People were always telling me to narrow it down and to think commercially, but I felt that the kind of music that I was doing was really designed for people who get bored very easily and want music to develop in the same way an epic film develops. Like a musical continuum and a kind of journey. All of this is a kind of voyage, which echoed my first album, Voyage of the Acolyte (1975). The idea of a voyage through different times, places, and climes was really what I was all about. My musical roots would stretch back like a time machine, and be also like a travel log, where I could travel around the world and do what I do today, which is with one man from Azerbaijan and a girl from Hungary playing the didgeridoo from Australia, and in tow I’ve got the influence of Morocco playing an Arabian oud. All of those things make up the whole and I’m determined to do constructions that shouldn’t really work. So I’m very non-formula except I have the Pan-genre approach, which means I mix up many different things that I find; anything from a washboard to a violin. I think that it all ought to be possible.

There are very interesting things going on in music today and I think that people have come around to this way of thinking. People have gotten very tired of formula throbbing bass drum thumping away endlessly through songs that have no real statements, but great singers embellishing on non-statements and non-senses. The other thing of course is there’s too much punctuation and rhythmic work, but over a nonexistent basic idea. If people would just serve the best interest of the song, you don’t need massive equipment, you just sit down with one guitar and one drum, or, it can even become the same thing I believe. I was recently watching a band on YouTube called Walked the Earth. Interesting that they were sitting around playing the same guitar and singing and doing harmonies and I thought, “Well, you know that’s not expensive, but very expressive and very, very good.”

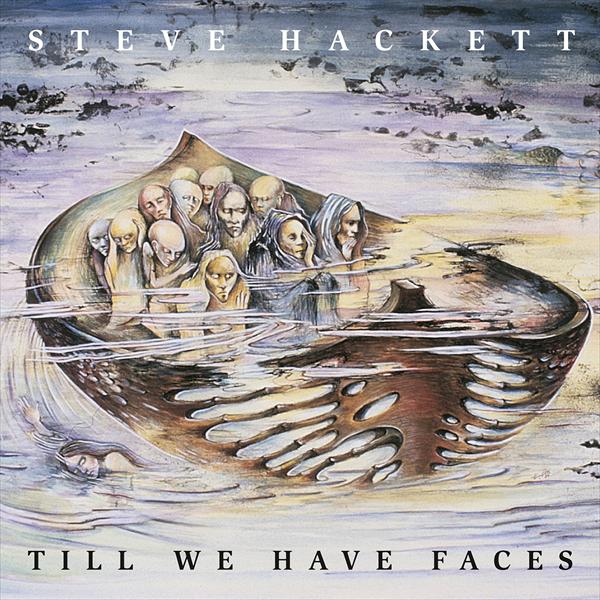

- Lamborghini Records

- Inside Out Music

CrypticRock.com – Speaking of musical journeys, your latest album, Wolflight (2015), has a clear theme throughout and is a very cohesive piece of work that needs to be listened to from start to finish. What was the writing and recording process like for this record?

Steve Hackett – Much of it was done on paper because I was doing so many shows that I had to plan out the recording sessions. Most of it took place in the imagination long before it was recorded; much like storyboarding a film. I recently read a book, a very interesting one about Alfred Hitchcock by a British writer called Peter Ackroyd, and he very perceptively noticed that Hitchcock almost got bored with the process of filming and he ran out of patience with directing actors. He just wanted what he drew up to be in the frame to then take place in the movie sense. I’m not saying that my process of recording is exactly the same. It’s not. I’m very hands on and I do play the instruments and I enjoy that for its detail and the virtuosity, but I’m motivated by more than that. It’s the idea that something can be planned out when you don’t have much time and you haven’t got a lot of time to experiment.

Nonetheless, I think that the human brain is marvelous recording studio within itself. We are recording studios and we are walking cameras, aren’t we? So much can be done in the imagination. It’s just a case of applying yourself and dreaming up the ideas, such as wouldn’t it be nice to have a didgeridoo twinned with a stringed drone and auto-tune the one to fit the other? Also, have a Tar from Azerbaijan being played and twinning the two. I had to perform with Malik Mansurov which was done entirely A cappella and I wanted to give him a sort of root note. We thought didgeridoo might be a good way of doing that instead of having the usual string drone underneath it.

- Inside Out Music

CrypticRock.com – It works very well on the record.While the album is heavily instrumental, there are also some really warm and full vocals as well. When you work primarily from an instrumental standpoint, is it at all difficult finding where to place the vocal parts or do they fall into place naturally?

Steve Hackett – I don’t think there’s any formula for writing a song except that I think the world is full of triggers. It might a painting you see, something you heard on TV, a news story, something that’s heard when somebody speaks that you thought you heard it a certain way but your interpretation might be more poetic or even myopic. Any of those things can act as a spur to take you further. Of course, the Beatles were marvelous at writing love songs and then having looked at all of those boy-girl scenarios, Bob Dylan’s influence upon them to expand their horizons was a very interesting one. Then they’d be doing stuff like “Eleanor Rigby,” where you have this supremely compassionate song written by young guys. They had the maturity to down their own instruments, put them aside and let the age old instrument take over in order to paint the character portrait so thoroughly. All of that I take as several role models for doing things, but that’s only one trigger. Another way, of course, is sitting down and strumming away with three chords and that’s all it takes to write a tune, or sometimes even less. Take Indian music; there are no chords. There are scales, but strictly speaking there are no chords as we know it. Then with the Blues, there are three chords in the main as an expanded arsenal right there and there.

It all depends what’s the intention of the song. Is the intention of the song to prioritize the lyrics, as in Dylan’s approach, or will it be to prioritize the guitar and the harmonica, in the case of Paul Butterfield? Indeed, if you’re Buddy Rich and you’ve got a big band, the accent is on the rhythm. It all depends, it is horses to courses. What are you aiming at and what are you trying to do? Or are you aware of the very simple but straight from the heart appeal of an act like Peter, Paul and Mary, who sounded wonderful with three great voices and two very basic guitar approaches? That’s all you need. You don’t need tons; you don’t need a pantechnicon to make great music. You don’t actually even need fabulous technique. You do have self-conviction and love for it, I think. It takes time and hopefully you’ll feel passionate enough about it that it will take a lifetime because the song is never finished; the song of you and everything you experience.

CrypticRock.com – The Progressive Rock scene really has blossomed through the years and you certainly are a pioneer guitarist of the genre. With that said, what is your opinion of the present Progressive Rock world in 2015?

Steve Hackett – I think what was interesting about the Progressive scene when I was starting out was that we weren’t aware that we were supposed to be Progressive, therefore I think we started out with less preconceptions. We didn’t feel we had to do long songs; it just worked out that way. Not all the songs were long. We were influenced by a mixture of Soul music, Motown, Blues and Classical music. From Ron Williams to Judy Collins to Joni Mitchell, and probably most importantly to Jimmy Webb, who came up with “MacArthur Park.” “MacArthur Park,” sung by Richard Harris, was chosen by four out of five of Genesis members, without conferring, when asked to choose their favorite single. I think it provided the template for many of the Genesis tunes. In other words, you had not just the first chorus but you had an extra verse, a bridge, and an instrumental work out in the middle. It gave time for the instruments to speak as well as the heartfelt lyrics.

Regarding the present Progressive scene, I think because so much is being done in this idiom, it’s hard for people not to sound a little bit like their preferences and their roots. All musicians have this problem. We are forced to be historians; it is just a case of where we apply the archeology. When I first heard of Progressive Rock, I became aware that free Jazz played a part in it as well. People were starting to base things on great Jazz men Ornette Coleman and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and that was part of the story too. It seems that Jazz aspects are marginalized in favor of the sort of haunting rhythms that accompany a track like “Watcher of The Skies” or “Schizoid Man” from King Crimson. I think it’s not the right way to go about it. I think the best thing is, if you’ve got an idea of a musical phrase, allow that to take you where it wants to take you. It can take you anywhere around the world and it could take you to any point in time. Don’t start off with too many rules.

CrypticRock.com – The ability to be liberated and try what you want to try in music is what makes it special.

Steve Hackett – I think you are right. Whatever it takes to liberate yourself musically. It often means avoiding a number of things that you would think would stalwart things. The usual props with which you might accompany yourself, such as the mainstay of Rock with electric guitars, bass, drums, keyboards. Yes, you could write a billion and one songs like that and many of them would be very good, but I think you should manage to do something, like raid the kitchen and get out the washboard or use the salt cellar for percussion. You might find when that’s recorded, it might sound just as good. Particularly these days when you’ve got a lot of ways of recording something and at one time we used a varied speed. Genesis, along with the Beatles, would vary the speed of the analog tape so that we might record at half speed in order for it to play back and have it sound more tingly and make a guitar sound like a music box.

These days there are many ways of doing that. You can instantly octave of something so that any instrument can sound far from its original source; you’ve got so many choices these days. You don’t really have to go to the obvious. I also think that is where it’s a complete shot in the dark sonically that often produces the strongest things. Songs built on slender threads often can be a real help by the time you’ve crafted something and finished it. The road less traveled has got so much to offer. You’re not competing in the same arena with everyone else. When everyone’s got a Mellotron and a Hammond organ, or facsimiles of both, it’s all going to end up sounding a certain way. Those instruments are wonderful of course and characterful in art, and I’m as guilty as anyone else of using them time and time again, but there are other things that you can do.

CrypticRock.com – The possibilities are endless and it is very exciting to explore them. My last question for you is pertaining to movies. CrypticRock.com covers music and Horror films. If you are a fan of Horror films, what are some of your favorites?

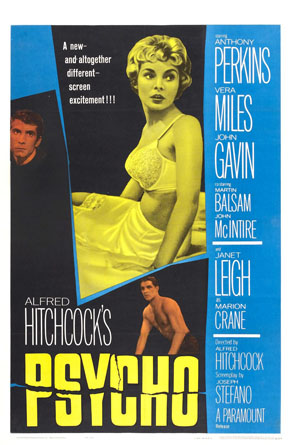

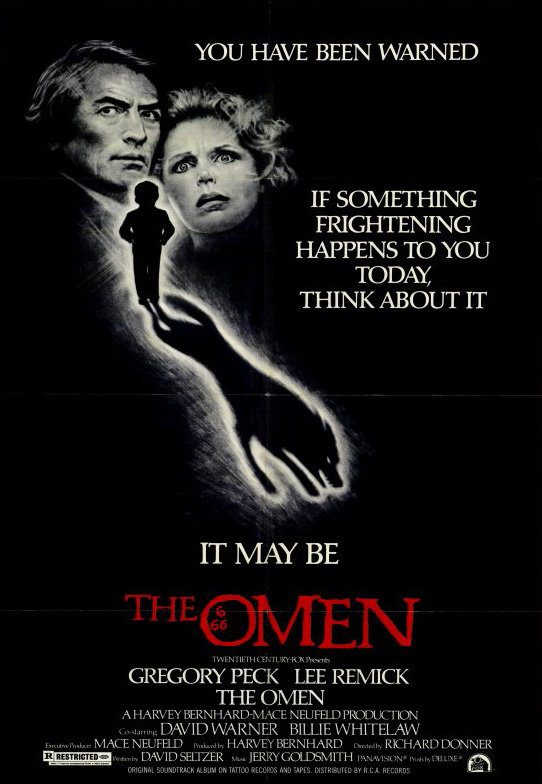

Steve Hackett – Funny enough I am. I love The Omen (1976). I love the score for Psycho (1960). It seems to be the most iconic of all of the Hitchcock soundtracks and of course, as you know, it influenced George Martin and influenced The Beatles. That percussive use of strings that I suspect everyone probably borrowed from Stravinsky from way back is there, but it is used uncharacteristically. Horror films often has very interesting orchestral scores, but I love films in general that have orchestral scores because then you get a sense of infinite depth. In the book I was reading about Hitchcock, he regarded music as the unspoken dialogue in a movie and the unspoken was very important to him. I often think films that have existed on an epic scale such as Ben-Hur (1959) and Gladiator (2000) even, those great Roman epics, have very large orchestral scores which seem to expand the frames. So even when you are watching it on TV at home or on the huge screen at the cinema, they still sound or look massive. That is because you’ve got that thing that the orchestra gives the film, a kind of infinite depth and imaginary sound fields filling in all the spaces. I particularly enjoyed Miklós Rózsa’s score to Ben-Hur. I still think it’s probably the best soundtrack of all time; it’s massive. I think the film would’ve been, although I think it’s a great movie, it would’ve been extremely wooden without that. I mean, it’s the glue that binds the whole thing together. It is a very emotional and militaristic score. It seems to combine the message that the various writers and directors were trying to convey with it

CrypticRock.com – Absolutely. A lot of films are like that, particularly in the Horror genre, such as Psycho and even The Exorcist (1973). These films are driven by the soundtracks.

Steve Hackett – I think many a time, a director could do worse than just let the music run. In the case of Hitchcock, during Vertigo (1958), there were many times where there was no dialogue, but it is not a silent film because you have the music. You have the music providing the tension and dictating the pace at times.

- Paramount Pictures

- 20th Century Fox

No comment