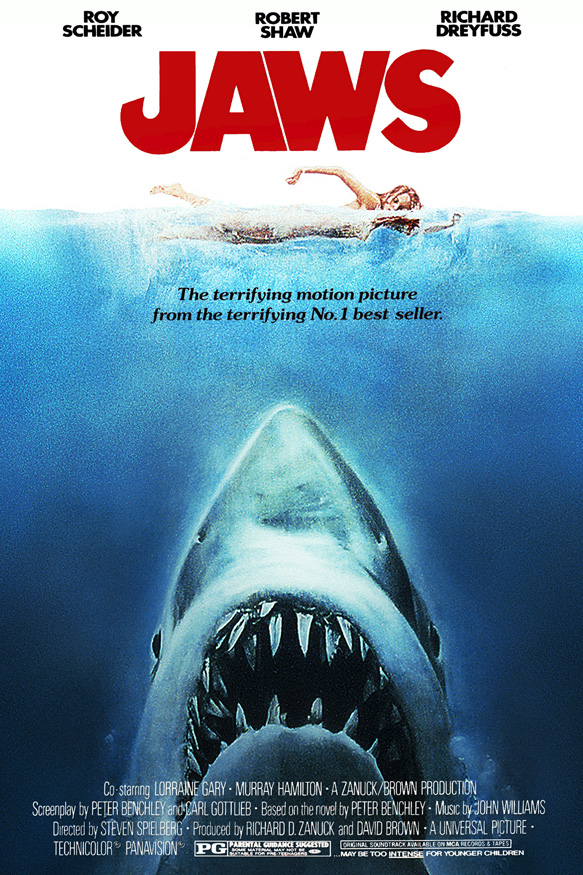

Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts has never been the same since the filming of Steven Spielberg’s killer shark movie, Jaws. Based on a true story from a series of 1916 shark attacks in New Jersey, the success of Jaws led to record breaking ticket sales for Universal Pictures and the beginning of a new genre of film – the summer blockbuster. Released forty years ago this week on June 20, 1975 through Universal and Zanuck/Brown Productions, Jaws took the world by storm, earning over $470 million, spawning three sequels and launching a line of accompanying merchandise, television ads and talk show circuit stops unrivalled by the studio up to that point. The movie was directed by a then relatively naïve Spielberg, who took the tiny $3.5 million budget, three well known actors – Roy Scheider (2010 1984, SeaQuest 2032 TV series), Richard Dreyfus (Close Encounters of the Third Kind 1977, What About Bob? 1991) and famed Shakespearian actor Robert Shaw (From Russia With Love 1963, The Sting 1973), who sadly passed away just three years after Jaws was released – and an Academy Award winning score by musical genius John Williams (E.T. the Extra Terrestrial 1982, Schindler’s List 1993) and constructed one of the most cinematically complete movies ever made. Jaws was produced by David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck (Cocoon 1985, Deep Impact 1998) while Peter Benchley, the author of the 1974 novel of the same name, collaborated with Carl Gottlieb (The Jerk 1979, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour TV series) to write a script that was peppered with adlibs and improvs added by both Spielberg and the actors themselves, providing some of the most oft repeated lines in cinematic history. Despite an elongated filming schedule, special effects heartaches, seasickness, a sinking boat and a doubling of the initial budget amount, the filmmaker took what he had and made it work, creating a masterpiece of terror.

- Still from Jaws

The island of Martha’s Vineyard was chosen because, even twelve miles out to sea, the ocean floor was only thirty feet down, allowing the finicky mechanical shark to function while also ensuring that land was not seen in any of the shots. Although the robotic fish, nicknamed Bruce after the director’s lawyer, broke down more often than it worked, this shark-shaped cloud had a silver lining, forcing Spielberg to imply the monster with underwater camera shots and that pile driving score, producing a terrifying experience that movie watchers had not experienced since Alfred Hitchcock’s peak twenty years previous. Spielberg had three separate sharks made by special effects designer Robert A. Mattey (Mary Poppins 1964, Eaten Alive 1977) – one showing on the right side, one the left side, and one fully skinned, each costing two-hundred fifty thousand dollars to build. Captured by overexcited fisherman thinking they had the real monster, the first shark caught in the film was real, although hooked off the coast of Florida rather than New England. Unfortunately, the trip up the coast was a warm one for the dead fish, and when it came time to film, the stink was atrocious. As the scene wrapped, the shark’s guts rotted through its body and dropped down into the back of its throat, delivering an even more noxious reek and sending both cast and crew scurrying. The shots of the shark attacking Hooper in the shark cage were of a real fish, although Dreyfus was replaced by a midget in a much smaller cage to make the shark itself look bigger. Initially, Hooper was set to die during this scene, but when the camera operators filmed the shark struggling in the ropes and breaking the cage, the entire script was rewritten to include this footage, letting Hooper escape and live. Hooper’s boat mate and antagonist, Quint, whose name means “fifth” in Latin, became the actual fifth person killed by the shark after Chrissie Watkins, Alex Kintner, Ben Gardner and Michael’s sailing instructor.

Spielberg paid locals sixty-four dollars a piece to run and scream on the beach, including Jeffrey Voorhees and Lee Fierro, who played Alex and Mrs. Kintner respectively. He even used his own dog, Elmer, to play Chief Brody’s sidekick. The real life animosity between Dreyfus and Shaw, combined with the tripled shooting time and constant, inclement weather, created an onscreen tension that worked perfectly for the characters of Hooper and Quint. Shaw’s drinking caused tension, as well as Dreyfus’ hubris and his belief that he did not belong on such an uncomfortable set after the success of his previous film, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974). This came to a head on the day Shaw wished out loud that he could quit drinking, so Dreyfus grabbed his glass and threw it in the ocean. The Orca itself sank to the bottom of the sea floor when ropes being used to rock the boat yanked a hole in the hull, sending cast, crew, equipment and film beneath the waves. On the last day of filming, the blowing up of the shark was scheduled to shoot, but Spielberg was nowhere to be found. Convinced that the crew would pull a prank on him to commemorate the last day of location photography, he hopped on a plane with Dreyfus before anyone realized he was gone. When the actor asked him how the final shot went, Spielberg answered, “They’re shooting it now,” sending Dreyfus into peals of hysterical laughter. This started a tradition for the director to be absent when the final scene of one of his films is being shot.

- Still from Jaws

The release of Jaws tripled Martha’s Vineyard’s tourist numbers, although most other seaside resorts experienced a downturn in numbers. To entice visitors, establishments had to resort to some creative attractions, including one seafood restaurant in Cape Cod proudly displaying the sign “Eat Fish – Get Even.” An unbridled hysteria took over the public in 1975, causing a boatload of overreactions: known as the Jaws Effect, fishermen by the hundreds piled into boats and killed every shark they saw; a beach in California was cleared by lifeguards when they thought they saw sharks in the water, which turned out to be only dolphins; and a beached, immature pygmy sperm whale being beaten to death in Florida when bystanders mistook it for a shark.

Despite the new fear of sharks – or perhaps because of it – Jaws spawned a cult following, including three sequels: Jaws 2 (1978), directed by Jeannot Szwarc with Scheider, Lorraine Gary (Ellen Brody) and Jeffrey Kramer (Deputy Kendricks) reprising their roles; Jaws 3-D (1983), directed by Joe Alves; and Jaws: The Revenge (1987), directed by Joseph Sargent, with Gary once again returning as Brody’s wife. Although they were technically box office successes, the public and critics were generally dissatisfied with them, resulting in the three films’ total domestic grosses amounting to barely half that of the first film. The Pixar movie Finding Nemo (2003) named one of their fish-loving sharks Bruce after Spielberg’s monster, and director Bryan Singer used one of Sheriff Brody’s lines to christen his company Bad Hat Harry Productions. Hollywood’s new obsession with sharks sparked The Discovery Channel’s Shark Week TV series, a phenomenon going on its twenty-seventh year this summer. Filmmakers tried to tie Jaws into everything, pitching movies such as Alien (1979) as “Jaws in space,” while Spielberg called his own Jurassic Park (1993) “Jaws on land.” Starting in 2005, Martha’s Vineyard has thrown a JawsFest festival during the film’s anniversary years. Two Universal theme park rides have been inspired by the movie, and the studio tour at Universal Studios Hollywood features an animatronic version of Bruce the shark. Three video games and two plays were inspired by the film – Nintendo’s 1987 release Jaws, Xbox/Playstation/PC’s Jaws Unleashed in 2006 and Nintendo/Wii’s Jaws: Ultimate Predator in 2011, along with 2004’s JAWS The Musical! and 2006’s Giant Killer Shark: The Musical on the stage. In 2009, the Los Angeles United Film Festival debuted The Shark Is Still Working, a feature length documentary made by an independent group of fans and featuring interviews with the cast and crew, narrated by Scheider and dedicated to Benchley, who died in 2006.

- Still from Jaws

Jaws became the first ever LaserDisc title marketed in North America, coming out in 1978, followed by a VHS release in 1980 through MCA Home Video and an elaborate 1995 Twentieth Anniversary Edition LaserDisc boxset through MCA/Universal Home Video that included deleted scenes and outtakes, a brand new two-hour documentary on the making of the film directed by Laurent Bouzereau, a copy of Peter Benchley’s novel and a CD of the movie’s soundtrack. Jaws was finally released on DVD in 2000 for the film’s twenty-fifth anniversary, along with an edited version of the 1995 documentary, production photos, storyboards and a huge publicity campaign. The first JawsFest in Martha’s Vineyard coincided with a thirtieth anniversary edition that included the full LaserDisc documentary and a previously unreleased interview with Spielberg from the set of the movie. The film finally received the Blu-ray treatment at the second JawsFest in 2012 with over four hours of extras, including The Shark Is Still Working documentary, and debuting in fourth place during Universal’s one hundredth anniversary celebration that same year.

Claiming an outstanding 97% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes, Jaws won many awards in 1976, including Oscars for Best Sound, Best Film Editing, Best Music and Original Dramatic Score, and was nominated for Best Picture. The film also won a Golden Globe for Best Original Score – Motion Picture and was nominated for Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Screenplay – Motion Picture and Best Director – Motion Picture, and garnered a Grammy for Album of Best Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or Television Special for John Williams, who had to leave his position as conductor at the Grammy’s orchestra podium to receive his award. The film is ranked highly by American Film Institute, garnering the second greatest thriller spot on their 100 Thrills list in 2001 and fifty-sixth greatest film ever on their 100 Greatest Movies list in 2008, while the shark itself placed eighteenth on their 100 Heroes and Villains list in 2003.

- Still from Jaws

In any other hands, at any other time or place, with any other music and using any other cast and crew, Jaws may have ended up on the bottom of a long list of ‘70s Horror movies. But lightning was caught in a bottle on the Orca back in 1975, and a perfect storm of moviemaking genius was formed solid and whole in the great maw of a broken mechanical beast. Many have tried to ride the wave of Spielberg’s brilliance, but none have even come close to making an entire generation as afraid of dipping a toe into the great, blue ocean.

- Universal Pictures

such great review! very well written