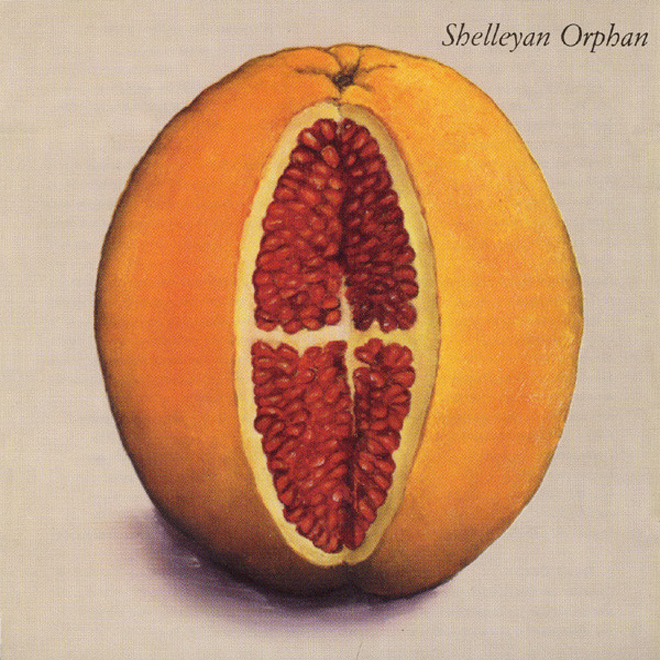

Sadly, there can no longer be any new albums by the exotic group known as Shelleyan Orphan. On October 4, 2016, its face, female voice, and half of its heart passed away quietly after a long battle with an illness. That was really a great loss to the music scene, for Shelleyan Orphan had always come up with beautiful and ethereal music that proudly wore the sonic badge of Baroque/Indie Pop in all its glory. Perhaps the pinnacle of the duo’s beautiful catalogue, 1992’s Humroot, recently celebrated a quiet but respectful 25-year anniversary this past May.

Shelleyan Orphan was formed in 1982, in Bournemouth, England, by Caroline Crawley (lead vocals, guitar) and Jemaur Tayle (lead guitar, vocals). Backed up by a collective of fellow artists and musicians whom included The Cure’s Boris Williams (drums) and Porl Thompson (dulcimer) and The Associates’ Robert Soave (bass), the duo got to release only four studio albums during their intermittent existence—the debut, 1987’s heavily Baroque Pop Helleborine; 1989’s follow-up, the more organic and poppy Century Flower; the fragile Humroot of 1992; and the intuitively-titled comeback but final opus, 2008’s We Have Everything We Need.

Released in 1992, on Columbia/Rough Trade, Humroot opened with the frivolously floating and reverberating rhythm of “Muddied-Up,” where Crawley’s coos drifted controllably midair. This served as a prelude to “Dead Cat,” which albeit morbidly-titled, was a subtle climb to rapture—guitar flickering, voice scatting, and bass rolling. Then relaxing the ambiance for a bit was “Fishes,” whose alternating time-signature changes made the instrumental melodies and vocal harmonies swim gracefully through the familiar cavalry of clouds.

The aptly-titled “Burst” remains to be Humroot’s highlight, both in musical flight and lyrical delight—a piano-led track glazed with layers of jangly guitars, staccato strings, and other Classical paraphernalia, and driven by the lovely call-and-response vocal duet of Crawley and Tayle, cheerfully celebrating life and playfully exulting the spirits. A sudden darkening of mood followed in the form of the slow, melancholic drone of “Sick,” where Crawley’s pained voice soared nonetheless. Then came the marching, Celtic rhythm of the majestically-arranged “Little Death,” further exhibiting Shelleyan Orphan’s penchant to make love with both utter morbidness and sheer joy on the same bed of midsummer pearls and plumes at the same time.

Waltzing its way next was the bouncy but graceful “Big Sun,” which exuded also a bit of jazzy, loungy, and rustic aura. This gave way to the similarly adventurous “Dolphins,” whose horn and woodwind arrangement, scathing guitar, and string flourishes highlighted Shelleyan Orphan’s Worldbeat tendencies—something that the duo further explored in the lone, eponymous 1998 album of their short-lived, one-off musical project, Babacar, which is a significant footnote to Shelleyan Orphan’s history.

A thirty-second acoustic-guitar mulling then prepped the dreamy, somber, acoustic excursion of “Long Dead Flowers,” where Tayle’s voice took the helm while Crawley’s graciously stayed softly, but equally felt, in the background.

Near the end of the sonic journey, the penultimate “Swallow” rolled its tribal rhythm smoothly but confidently, sure of its direction, which was—to the very humroot of Shelleyan Orphan’s sound, classic, medieval, instinctive, primeval. Finally, Crawley, Tayle, and their comrades in Shelleyan Orphan wrapped up their sonic art masterpiece with the sparse, flowing, and pulsating thoughts, whims, petals, fiddles, harmonics, dreams, wishes, and sentiments of “Supernature on a Superhighway.”

Many people in any given generation, in their midlives, lament their false perception that there is no more good music out there. However, little they do know that the problem actually resides in their own jadedness, laziness, willful ignorance, or simply, failure to take precious time in finding the pearls from the oceans, the diamonds from the caves, and the beauty in the hearts of the world’s music archives at large. Shelleyan Orphan’s albums are just some of these half-forgotten gems that many music enthusiasts either willfully ignored or failed to discover.

So, in celebration of Humroot’s twenty-fifth anniversary and, more importantly, in honor of Crawley’s memories and in remembrance of her band Shelleyan Orphan, may we, all lovers of beautiful and sophisticated music, dim the lights, kindle some candles, play Humroot, and sit silently and solitarily in our respective corners and let the songs cast their mystical glow on each one of us.

No comment