To catch a killer, one must attempt to think like a killer, and the concept of probing the mind of a serial killer is one that has been addressed by multitudes of films. Fifteen years ago, on August 8, 2000, New Line Cinema released a film that took a much more literal approach to this idea, giving ample screen-time to the surreal, disturbing, and sometimes unsettlingly beautiful visions that such a mind might harbor. The Cell, featuring striking visual effects and a fresh approach to the Crime Drama genre, still holds up today.

With an original story by Mark Protosevich, who also wrote the screenplays for I Am Legend (2007) and the American remake of Oldboy (2013), The Cell was a box office success, ultimately making over three times its original budget of $33 million. The Cell was the first feature-length film for the Harvard-educated director Tarsem Singh. Prior to that, Singh had worked mainly on commercials and music videos, including the award-winning video for “Losing My Religion,” by R.E.M.

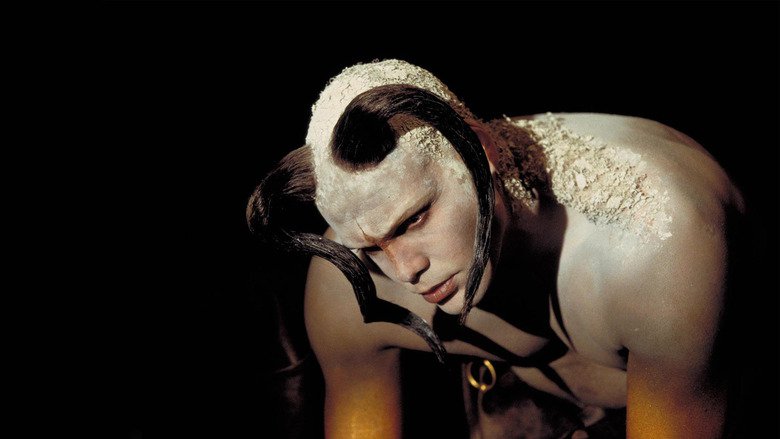

- Still from The Cell

In spite of its financial success and stamps of approval from such respected critics as Roger Ebert and Peter Travers, The Cell never quite secured a spot among the vast collection of modern films that are considered great. Among fans of the multiple genres it straddles, The Cell is somewhat alienating — too strange for those seeking a classic Thriller and featuring “science” that is too vague and implausible for fans of Sci-Fi. Horror fans might have objected to the casting, which included Pop star Jennifer Lopez in the lead role (although she had certainly proven her acting ability in the 1997 film Selena). Nevertheless, there were those who loved it and who now regard it as one of the more underrated films of its time.

The bare bones plot of The Cell is that of a Crime Drama/Thriller. Due to the device of probing the killer’s mind, it is reminiscent of Thomas Harris’ Hannibal Lecter series, most notably The Silence of the Lambs, which also features a female protagonist. In The Cell, Jennifer Lopez plays Catherine Deane, a child psychologist who specializes in working with coma patients. A Science Fiction element is introduced with the technique Deane uses, which involves a procedure that allows her to enter the subconscious minds of her comatose patients.

When F.B.I. Agent Peter Novak (Vince Vaughan: True Detective, 2015; Anchorman and Anchorman 2, 2004 and 2013) enlists Deane’s help in finding the latest victim of serial killer Carl Stargher (Vincent D’Onofrio: Jurassic World, 2015; Daredevil [T.V. series], 2015), Deane must enter Stargher’s disordered mind to search for clues. Although Stargher is safely in custody, he has slipped into a coma, and a young woman, Julia Hickson (Tara Subkoff: The Notorious Bettie Page, 2005) is still trapped in Stargher’s torture chamber.

- Still from The Cell

Stargher’s modus operandi is to trap victims in a glass case and slowly fill it with water via timed intermittent spurts from a sprinkler system installed in the case. Once the victim has drowned, Stargher “cleans” the body and displays it as one would a doll. Deane must explore Stargher’s subconscious mind and figure out where Hickson is located before the case fills up and Hickson is drowned. She does this at great risk to her own sanity: the longer one spends in a disturbed mind, the more one risks being trapped there. Predictably, Deane does indeed get trapped, and Novak must also enter Stargher’s mind to help her.

The scenes that take place in Stargher’s mind are what ratchet the film up from Thriller to Horror. The imagery here is not only violent, but also bizarre. Singh took inspiration from works by artists including Damien Hirst — the vivisected horse resembles Hirst’s 1996 installation titled “Some Comfort Gained from the Acceptance of the Inherent Lies in Everything,” which displayed a cow and a bull separated into twelve segments — and Odd Nerdrum, whose painting “Dawn” (1990) is the source of the image featuring three identical women, seemingly frozen in place, gaping at the sky. (Nerdrum’s painting shows four women, but the imagery is otherwise close to identical.)

A number of paintings depict the martyrdom of Saint Erasmus, who was executed by means of an intestinal crank, a device used to torture Novak in The Cell. There is evidence that some of Singh’s favorable images were also inspired by art. For example, when Deane attempts to heal Stargher by inviting him into her own subconscious, she appears in a red robe similar to that worn by the Virgin Mary in many medieval and Renaissance paintings.

Although there is no arguing that The Cell is visually stunning, many have criticized the film for being “all style and no substance.” However, even if one were to eliminate the surreal imagery, the plot would still be compelling, albeit somewhat familiar, especially fifteen years later. The frame story might be the most effective part of the plot. Prior to being approached by the F.B.I., Deane had been working with a comatose child, Edward Baines (Colton James) who is similar in many ways to the child version of Stargher. While it is obviously too late to save Stargher, there is still hope for Edward, and in delving into Stargher’s psyche, Deane has gained new insights and is now better equipped to help her young patient. Edward’s story, however, is largely dismissed once Stargher enters the picture.

- Still from The Cell

Perhaps the most challenging element of The Cell and one that might still put-off viewers today, is that in providing a visual narrative of Stargher’s harrowing upbringing, the film asks viewers to empathize with a twisted serial killer. The implication is that, although Stargher is in fact evil, the person responsible for cultivating that evil into existence is Stargher’s abusive father. Clearly, Stargher the child was innocent — acutely compassionate, even, as evidenced in a scene where, in a desperate act of mercy, he drowns an injured bird, presumably to prevent his father from being able to harm it. Deane attempts to appeal to the young version of Stargher for help, but, in a heartbreaking reminder of the cycle of violence, the child seems to be just as frightened of his adult self as he is of his father. Stargher the Demon King, with flowing robes enveloping an imposingly muscled body, reigns supreme in this world. After all, as long as he retains this form, no one will ever harm Carl Stargher again.

- New Line Cinema

Ive always felt this film was subpar on every count.

Could have been much much better.

It was an opportunity for stunning brillance that peters out at mediocre. Ive never heard of anyone say anything about the film other than its mediocre at best. Its interesting to hear praise. I never have before.

At the time of its release, it was perceived as too formualic for its own good and a terrible waste of an opportunity for phenomenal wardrobe, set design, and haunting imagery that COULD have been remarkable but was not.

There was positive buzz while the film was being made but when it was released to overwhelmingly negative reviews, it was pretty much forgotten about. Ive never heard anyone praise it.

Interesting.

I’ve always had an extremely positive take on this film & have always been surprised by the disdain it receives. I am someone who falls in love with how a movie looks and feels over how special the plot or dialogue are, however. If you want amazing prose, read a book. If you want visuals and feel, watch The Cell. Plus it has JLo watching Fantastic Planet.