There is something inspiring about an artist who follows their own path regardless of trends… yet still finds success along the way. A singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and composer, Loreena McKennitt is one such individual who has been marching to the beat of their own drum over the last four decades.

Internationally acknowledged for her beautifully pure soprano singing, McKennitt has created music that is both majestic, yet educational. Compositions that linger outside the box of mainstream Pop, her work is much more worldly, with various Folk, Celtic and Middle Eastern influences. Always telling a story and creating imagery in sound, McKennitt’s unique approach has earned her a massive amount of success with over 14 million records sold across the globe.

Still finding new ways to expand her own life experiences, she recently put out the new live album Under a Winter’s Moon which melds traditional Christmas carols with other more broadened elements. Humble, yet proud of her artistic independence, Loreena McKennitt recently took the time to chat about her career, perspective, concerns for humanity, plus much more.

Cryptic Rock – You have been involved in music professionally for nearly four decades. Taking a very unique, artistic path, you still found success in the mainstream along the way. Before we go any further, how would you describe your incredible musical journey to this point?

Loreena McKennitt – It has been an incredible journey in many ways. As a young girl I aspired to be a veterinarian, and if not, to work in wildlife or forestry. So, I maintain that music chose me, rather than me music. And really once I got interested in Folk music, which then went on to the Celtic Folk music, it was impossible to appreciate the traditional music without understanding its historical context from a social, economic, and political standpoint. So, I started studying particularly Irish history, and later on around 1991, I attended an expedition in Venice that was the most extensive expedition ever assembled on the Celtics. It was at that time I learned that there was this vast collection of tribes that had fanned out across Europe and into Asia Minor that dated back to about 500 BC.

When I think of this whole journey of what has more less been characterized as my career, it’s also been an incredible act of self-education; in terms of geography, cultures, history, as well as music and musical instruments. From that standpoint it’s been very, very rich. It’s certainly become far more successful than I could ever have imagined. Particularly given that the music I’ve created is not what one would call or consider an overtly commercial musical footprint. I think that in some ways indicates the music industry has been off kilter with respect to certain artists and what the public might be open to. It’s been a heavily managed, gatekeeping kind of industry; it still remains so, but now it’s moved more into the tech companies.

I feel very fortunate to reach the pinnacle of my career before ’98 and the digital nightmare started. I have been able to continue my career as a result of that.

Cryptic Rock – It’s inspiring and very compelling to hear how it all developed for you. The mainstream entertainment world is primarily focused toward modern Pop, and record companies have always sold that. This in mind, you broke through with a style that is deeper and more cultural. How redeeming is that for you?

Loreena McKennitt – I think part of it is what I’ve been doing, but I think there are probably other artists that deserve more successful careers than they went on to experience. I think one of the unique aspects of my career development from the very get-go was I financed my own records and did all the way through. So, once I started engaging with a major record company, like in 1991 with Warner Music Group, it was a licensing deal and more like a partnership.

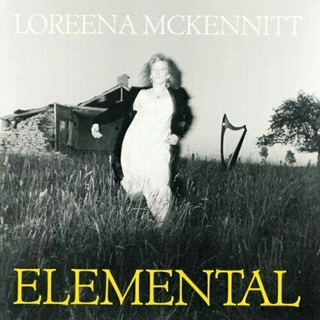

From 1985 with my first recording (Elemental) through 1991, when I released The Visit (which was with the Warner Music Group), I spent 5-6 years building my career brick by brick. That includes by starting with busking on the streets of Toronto; particularly at the St. Lawrence Market on Saturday mornings. I would sell my cassettes, I would set up little accounts at specialty, health food, and some record retailing shops. I also started to produce my own little concerts at church halls and libraries. This kind of grew organically over 5-6 years. So, by the time 1991 came along and I was producing my fourth recording, which I financed, now it was being distributed by a major label. That was a significant component. I continued to manage my career myself with my own staff, rather than involve a manager. All these come into play, not just the creative footprint.

Cryptic Rock – Absolutely. You also had the creative freedom to do what you wanted because you were in control; that is how it should be for an artist. There was a gap of time where you stepped away from music due to personal tragedies. Sometimes when these types of things happen it is difficult to find new inspiration again. That said, was it difficult to find that spark again?

Loreena McKennitt – Well in ’98 when I lost my fiancé in a boating accident, we were already planning for me to take a pause in my career for a while. It just wasn’t the way I was intending to do it. Even during that time, by 2000, a couple of years after that very tragic event, I purchased a heritage school, and we converted it in those years to a family center. We also set up a water safety fund and raised between 3 and 4 million dollars based on a live recording I made in ’98 in Toronto and Paris.

Setting that water safety fund up and administering it took a bit of time. By 2003 I was ready to get out and start doing some research for recording; I started traveling to Mongolia and China. It was a slow work up to An Ancient Muse (2006); it took time to record it. That time was still quite full and busy, it wasn’t all to do with my career. Setting up the fund as a response to that tragic event was something I felt was really needed. I hadn’t really felt I was leaving my career as it were.

Cryptic Rock – Yes, and as we know, you did eventually return to recording music. Speaking of live performances, you have done an abundant number of live recordings through the years. There is something truly special about a live concert event… So, is it safe to say you enjoy performing live?

Loreena McKennitt – Yes. I work with an exceptional group of musicians and it is just elevating to work with them. (Laughs) I would almost be happy enough to play music with that alone, but then to be able to share that with other people is a glorious icing on the cake. I enjoy being involved in playing music and singing with others when that occasion occurs.

The live recordings certainly have a different electricity and intensity to them. The stakes are always high because anything can happen in a live performance of course. You are operating that much closer to the edge; whereas in a studio if you flub things, you can go back and do it again and again. There is also unique chemistry and a dynamic that occurs between the audience and performance that I think elicits from the performance a different kind of performance. I guess the Live in Paris and Toronto (1999) was one of our first. We have done quite a few live recordings since and we are just launching this new one now.

Cryptic Rock – Yes, that leads us into your latest live album, Under A Winter’s Moon. A storytelling album, the listening experience is very visual. What led you to record this collection of songs for this live album?

Loreena McKennitt – Well, this performance that we gave was a series of four or five performances in the sanctuary of a local church where I live in Stratford, Ontario. The impetus for us to do those performances was much a response to cabin fever setting in as a result of the pandemic. I said to my colleagues in November of 2021, “Do you think we can pull together quite quickly some pieces and musicians that we can present in about a month’s time?” We decided we could and we did.

I often associate storytelling with this time of year. I love the different kinds of stories that I have been told and I felt that was part of the fabric of the presentation. In the spoken word department, the whole second half is the glorious A Child’s Christmas in Wales (1952) by Dylan Thomas, and it’s performed by one of Canadians most accomplished and wonderful actors, Cedric Smith.

We also wove in content that comes from the Indigenous point of view. We know that Christmas is based on the birth story of the Baby Jesus, but I wanted to open the presentation wider than that in this performance that wove in a more Indigenous worldview. The first story is the birth of North America, which some Indigenous people refer to as Turtle Island. I drew upon a friend of mine who is Indigenous and comes from a Cree Community, Tom Jackson; another one of Canada’s most accomplished actors and singers. I asked him to record that for our performance, because he wasn’t able to be there live.

I then asked a young gentleman by the name of Jeffrey “Red” George from another Indigenous community close to where I live to play flute, but also to give his perspective of the winter season. I think part of this was also driven into, as we’re living in a time of climate emergency and environmental emergencies, that our whole engagement with the natural world needs a refresh. There is a divinity in the natural world and sacredness in the natural world. And I feel this can come through so beautifully from some of the Indigenous worldviews.

Cryptic Rock – It is truly exciting to hear about the concept behind this. As mentioned, the concert creates very visual imagery. Have you considered releasing a concert DVD of this collection of songs?

Loreena McKennitt – We did tape it last year, but we quickly just said we wanted to tape it even just for archival purposes. We ran out of time, but we also wanted to just get it on its feet and see how it worked. We recently completed a small little tour in Southern Ontario which went on over the weekends through the 18th of December. We are looking at 2022 as the second chapter, and there might be the third chapter in 2023. For sure we will be putting it out on vinyl, but we are looking to see if there will be any radio programs such as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. I think visually it could work really well; we just haven’t gotten that part figured out and if that is what we are going to do.

Cryptic Rock – It will be interesting to see what happens with that. As you mentioned, you do put a significant amount of research into the songs you record. What led you to choose the pieces for Under a Winter’s Moon?

Loreena McKennitt – To be honest they were pieces that were most familiar to me. Some of them came from my second recording, which I recorded on location in 1987 at two locations in Ireland; one was A Benedictine Monastery near Limerick, the other was an artist retreat up in County Monahan. The third location was actually at The Church of Our Lady in Guelph, Ontario. That album was called To Drive the Cold Winter Away (1987). When I was considering the material for this one, I thought we could at least go back to some of the pieces on that recording.

Then there is also the “Huron Carol,” which is not on that recording. The “Huron Carol” is a very interesting piece and I’ve only recently learned a great deal more about it. In Canada it was often presented as the oldest Canadian Christmas Carol written by Jean de Brébeuf. But it was brought to my attention about a month ago, that although it dates back to the 1600s and Jean de Brébeuf, the original lyrics were in an indigenous Wyandot language. The Wyandot living up near Ottawa and The Wyandot lyrics were somewhat different from the English. The English lyrics were written by a man named Jesse Edgar Middleton in 1927 and he heavily skewed them. It feels like it’s this very delicate and difficult subject of whether this was an act of conversion into Christianity and an act of colonization. There are some in the Indigenous and the Non-indigenous communities that feel the piece is a bridge between the communities, but there are others who feel quite different; they feel it was a very deliberate act of conversion.

Here in Canada around 5-6 years ago we had a truth and reconciliation commission that went across the country and took testimony from many indigenous people about their life experiences. This included residential schools, and a year and a half ago they found at one residential school one mass grave in Kamloops with 215 children… and this is knowing there were probably a whole lot more graves all across the residential schools in Canada. The subject of indigenous reconciliation is really very front and foremost in a lot of Canadians’ minds these days. It was one of the other reasons I wanted to bring in the Indigenous view to this album.

First and foremost, it was a world view and a view of a connection with the natural world. I think that is incredibly valuable and that we have as a species drifted so far from this; bringing us to this climate and environmental disaster. It’s also, for me, an act in the process of reconciliation. I am in charge of my concerts and I wanted to open up the doors for this kind of content. I initially chose “Huron Carol” not knowing all this other complicated, difficult history, but now I do, and I speak to it in our performances.

The other carols in the second half, found within the body of the Dylan Thomas piece, I wanted to find pieces that may have been sung or heard during his time and where he lived. Those are much more familiar and conventional carols.

Cryptic Rock – It is a good balance and it brings light to some topics people should stop and think about. You mention our disconnect with nature, but how about our disconnect with our souls. It feels like we have lost our souls with all the technology, the constant stimulation from social media, etc. You release your music in physical format, and it also feels like we have lost the connection with music itself because of the effortless streaming of it. What do you feel about that?

Loreena McKennitt – (Laughs) I am not sure how much homework you did on me, but you are opening up one of my pet peeve doors. I currently equate the unintended consequences that have come with this digital revolution to the unintended consequences of fossil fuels. I think the consequences are as big, if not bigger. I have been reading a lot and following experts who have been doing research on this for over 10 years.

It partially began when one half of the music industry got decimated first through Napster and BitTorrent sites, but even now in streaming. Artists simply do not get compensated the same way they did when there was an analog world. You have to be in a very elite category in the millions and millions of streams to make a living, or to make a creative footprint that may be more expensive. In my case, I bring in musicians and instruments from all over the place such as Turkey and Greece, and that is quite an expensive musical expression. There is just not a viable business model now for that side of the industry, so it has driven everybody to have to go touring. Touring is always not possible for everyone, and moreover, once you start having a family, it’s not good to be off on the road with your family or away from your family.

It goes on to newspapers and the traditional media, which have not been perfect, but I still felt there had been mechanisms in place that held the traditional media accountable that simply was not holding, and is still not holding the digital media accountable the way it needs to be. I think the horses have bolted so far from the door and it’s an accountability mechanism that needs to be done on a global basis with treaties. I know Canada has been a part of a grand committee with the UK, Australia, the United States, etc. There are just so many ways that the digital world with surveillance capitalism invades our privacy that is used in China… and now it’s come to our doorstep.

I see our democracies being fiercely compromised by this unregulated technology and not least which is our children. There are many specialists and experts such as Dr. Leonard Sax who has written extensively about child development and the negative consequences of the premature use of technology or the overuse of it. There is also Dr. Aric Sigman who talks through chapter and verse of all kinds of medical conditions including myopia in children. There are the gaming addictions, hard porn, the bullying, suicide… it’s just an absolute catastrophe in my view.

I think about it from an anthropological standpoint too. Robin Dunbar, who studies primates, research showed that the ratio between the size of a neocortex of a primate and their group size was related. For us as a species that sweet spot is somewhere about 150 to 200. I think what has happened is we are living so far now from our physiological budget. We have stretched ourselves beyond the breaking point and we don’t know what is wrong with us as a species. There is mental illness, loneliness, but people are feeling the symptoms of it in spades.

I believe there should be a right to live analog. (Laughs) Because I think from an anthropically and physiological standpoint, that’s what we’re built for. We’re not built for the speed, volume, and complexity of this contemporary world. Gabor Maté and Gordon Neufeld spoke to this in their 2004 book Hold on to Your Kids: Why Parents Need to Matter More Than Peers. This all really started after television entered the home after the second World War. That’s just a fraction of what I have to say. (Laughs)

Cryptic Rock – You are speaking the truth. The frustration part is society creates a problem, but then counteracts it with a resolution such as medication. This is all while seemingly intentionally manufacturing problems.

Loreena McKennitt – Yes, some people are in a better situation to be studying all of this; others are just barely surviving, if that, and don’t have the wherewithal to be able to exam and take on board the big picture from a high level. It is certainly a subject I feel passionately about. I do connect it back to climate and the environment. If you don’t have time or an intimacy with the natural world, you’re not going to love it, and if you don’t love it, you’re not going to save it. It does mean choices have to be made in a household.

Experts again all say look, kids don’t need this technology until at least 16 years old where the brain is more mature. But it’s been sold into the educational systems, and what is really ironic is there are a lot of accomplished, high-level families in Silicon Valley that send their kids to Waldorf schools where there is no technology until maybe grade 8 or so. I read a piece in The New York Times that there appears to be a class divide; those who come very influential settings will have their kids in outdoor educations and the tech will be a relatively small part… where as those who are far worse off, it’s all tech, it’s lanced with tech from the time the kids are less than 2 years old.

It’s a very concerning thing. If you don’t have your brain and body, how can you interrupt what’s going on in your world and your democracies… This gets into Nicholas Carr’s book, The Shallows (2010), which he wrote over a decade ago. He said the research he had been studying showed the premature use, misuse, and overuse of technology is changing the physiology of the human brain and it’s reverting back to a pre-printing press physiology. This is grave!

No comment