Walking an extremely fascinating lifepath, some may recognize Stephen Macht as an accomplished Hollywood actor with a lengthy career dating back to the ’70s, spanning 40-plus years. Just a part of who he is, Macht comes from a world of academia, having once been a struggling theater actor who had a few defining moments that led to richer success and longevity.

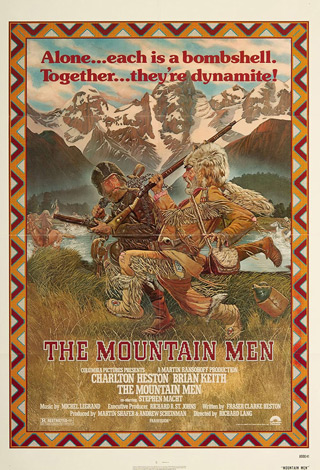

Starring in a list of films and television series (including early roles such as in the syndicated 1978 miniseries The Immigrants, and beloved roles in later films such as 1987’s The Monster Squad and 1990’s Graveyard Shift), Macht is still more than an actor. Also a father and once a college professor, he would later find deeper purpose as he studied to become an ordained rabbi.

Truly a man that has lived many different lives in one lifetime, Stephen Macht sat down for an introspective conversation about it all for what is a 2-part interview. In part 1, he offers insight into where his career began as an actor, highlights defining moments, and more.

Cryptic Rock – You have sustained a long career in the arts as an actor in theater, film, and television. A lot to reflect on, how would you describe this journey?

Stephen Macht – I think it probably began at Dartmouth. When I went to high school, I had never acted. My brother was an actor in high school and at Dartmouth, but he left Dartmouth. And when I was there, there were no women.

I tried out for the winter baseball team, and that didn’t happen. I was a swimmer in high school, but all I saw were six-foot-three guys with bubbles in front of me. I mean, I only saw their feet, and I saw that it was not for me. I was in a philosophy class, and some strange guy was diddy bopping behind me. There were 300 guys in this introductory philosophy course. And I heard this, and I turned around and saw this guy who, later, I learned was Michael Moriarty. He became my roommate at Dartmouth and eventually became a very famous guy.

He started writing plays and one-act plays. I got involved in one-act plays, and then I got into a fraternity where there are some actors. I acted and directed in that. Then one thing led to another. And at Dartmouth, in my senior year, a very special guy, whose name was Michel Saint-Denis (who was the reason Stanislavski came from Russia to France and then to the United States), opened at the Hopkins Center, our new Performing Arts Center in 1963. He delivered the keynote address, and he came to see a play that I was in, Danton’s Death, where I played the executioner Saint-Just in the French Revolution. After he came up to me in my dressing room, patted my face, and said, “Mr. Macht, you have a wonderful face. You don’t know how to use it.” He said, “I send you to England, and they train you there.” That same night, we had a party, and I brought my date. He looked at me and said, “Who is that girl?” I said, “That’s my date. It’s the first date we’ve had.” He said, “You should marry her.” Two years later, I did marry her. I also went to the academy, and I began training there.

Then my mother became ill in ’64, and I returned home. So I only had a quarter of the training. Still, it was profoundly influencing me on how to begin studying Shakespeare and how to internalize and become the character you are studying. One thing led to another, and I couldn’t get any work in New York. I was there for five months, and I couldn’t get any work. There was a time before Dusty Hoffman broke it open for guys who were ethnic types. I couldn’t get any work, and I remember finally being offered an understudy and stage manager for Arms and the Man (a George Shaw play). I asked, “Could you give me $15 a week because I had no money?” The guy said, “Yeah, but you have to talk to the producer for that.” I did, and he said, “Yes.” So, I came on a Monday morning, I had a raincoat that no longer repelled water, and the stage manager came out and said, “Stephen, we found somebody who would do it for nothing.” And I decided, “Fuck this. I’m not waiting around for this.”

So a mentor of mine, who was a professor at Dartmouth, said, “Look, Steve, you enjoy this stuff. Why don’t you go get an MA, a PhD? You enjoy talking about it, and you’ll find your way.” I did exactly that. I took an MFA in playwriting at Tufts and then worked in a company for my assistantship at Indiana University. For a year, after we had a baby, my wife said, “This is not working for me. You’re on the road four days a week.” So I gave that up. I became an acting assistant teacher, finished my PhD, and wrote a dissertation on the history of the London Academy of Music and Dramatic, which enabled me to return and finish my training in 1968. That was a seminal year for me.

I both wrote, spent halftime in the British Museum, and interviewed everybody who had anything to do with that school, and then did original research on how acting training came about in England first as a training for opera singers. There was no acting training, but they had to learn the Delsarte method. And I traced. It was older than the Royal Academy, the London Academy. So I traced the history, and I wrote a book. That allowed me an intellectual experience of everything and the training. And I came back and first got a job teaching at Smith College as the head of the acting department. I was way over my head; I had no professional credits. I had done several small roles at the Theatre Company in Boston.

Anyway, so I started to teach. As I taught, I decided, you know, I really want to act, and I started acting there at Smith in the productions I was doing. It finally led to going to New York, where the department chairman at Queens College had been my formidable acting instructor in Shakespeare in England. He came to the United States, and he hired me as a low man on the totem pole. I started teaching from 8:00 to 10:00 every morning, Monday through Friday, in 1970. The rest of the time, he said, “Look, you want to act. Act. I’ll take that for your publishing.” And I started in little parts, nine lines in an off-Broadway play called Vivat! Vivat Regina! with Claire Bloom and Eileen Atkins.

I took understudy parts, and everything was built over five years; I was humbled. I taught acting and literature from 8:00 to 10:00. I directed plays there. I had to do one every other semester. For five years, I hustled. Finally, it led to a role in a wonderful play called When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder?, which drew a lot of attention to me.

It also drew the attention of a new young British director, Robin Phillips, who took over the Shakespeare Festival at Stratford, Ontario, Canada. And he offered me all the male role leads. He wanted a young, inexperienced but hustler to sort of wake up a stayed tradition. He was a rebel, and I was a rebel. I went up and auditioned for him and one of my idols, William Hutt (a great Shakespearean actor who wanted me to play Orsino in Twelfth Night). He is the lyrical Duke, and everybody had played him as music be the food of love, play on. Well, at my audition, I looked up his name, and Orsina means bear. I played him in front of those two guys with a big, thick, hard-on, running down his leg, saying, “If music be the food of love, play on, give me surfeit of it. Let me get laid.” He’s in love with a princess who doesn’t love him. They became hysterical, and they gave me all the leads.

Cryptic Rock – That is hilarious. And what did this all lead to?

Stephen Macht – Most importantly, my role as Proctor in The Crucible led Universal scouts to sign me at the end of my teaching career in ’76 to come and move my family and begin acting for Universal in TV and motion pictures. They guaranteed me $12,000, even if I did not work, and that was in 1976. I was making $16,000 as a professor in New York. So my wife said to me, “We’ve got to do this. This is the adventure.” At that time, we had three children, and we moved.

They spoon-fed me two talent scouts who were like agents within Universal. They had a Young Star program, and they just called directors and got all breakdowns. They would say, “Stephen is going to appear as this and that and this and that.” There was no auditioning. They just fed because they wanted to build their talent so they could become TV or film stars. They were grooming me to have a series. I made something like 50 grand that first year. For a guy who was making $16,000 as a teacher, I thought, “Jesus Christ.”

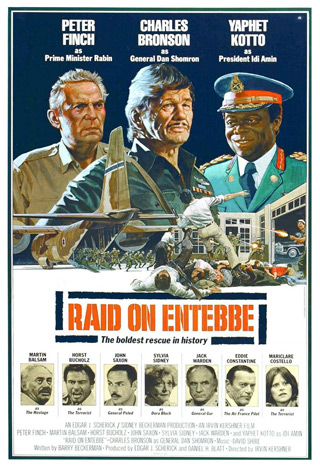

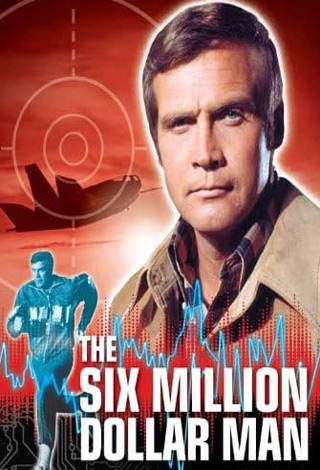

I appeared in everything they did. I appeared in The Six Million Dollar Man, and I had a spinoff, which was a pilot. I starred in one of the first miniseries, not for ABC, CBS, or NBC, but for educational TV, The Immigrants. I starred that, and Sharon Gless was my female lead. They were building my career. I started doing movies, more television, and that was the end of the ’70s and ’80s.

It was really popping along. And that led to me being called in because the woman who was Gene Roddenberry’s head writer on Star Trek saw me as Proctor in The Crucible at Stratford. She said, “If you ever get to LA, contact me. We’ll see what happens.” I didn’t know who she was, then whenever they were redoing Star Trek, she called me in.

She says, “Gene wants to see you.” I said, “Gene, who?” She said, “Gene Roddenberry.” And I said, “What for?” She said it is Star Trek.” I said, “It’s already been done. Shatner did that.” She said, “No, he wants to see you.” So I came in, and he says to me, “You are my next Picard.” I said, “I don’t know who that is.” He said, “He’s the lead!” I said, “I don’t want to do that,” And he said, “You’re a really lucky guy. You have a good friend here. She’s taking clips of everything you’ve done, and I think that you’re the next guy.” I said, “I don’t want to talk to people with seven heads for the rest of my life.” He said, “It’s not about that.” I said, “What’s it about?” And at that time, I had not really gotten deep into my Judaism. He says, “He’s Moses in space, leading his people through the desert. They got to discover who they are.” I said, “What?” I said, “Come on, Gene.” I said, “If you’re such a big shot, just offer it to me.” I had all kinds of piss and vinegar as a young guy. He said, “I’m trying to say I want you to do it. You’ve got to read.” I said, “I’m not reading. You’ve seen my shit. You think I can do it or not?” I had all that kind of stuff going on; what an asshole I was.

At any rate, I went in, and he said, “You’ve got to meet the studio head.” So I go in, and there’s a big room, and they talk to me, and Roddenberry, who was sort of executive producer, says to me, “Stephen, you sure you don’t want to read?” I said, “It’s agreed that I don’t have to read. You’ve seen my stuff. You either want me or you don’t. This meeting was just to get to know me. If you can’t tell what I’m going to do with Picard after this meeting, then what can I tell you?

He said, “Okay. Thanks very much.” And I walked out, and there in the hallway was a bald guy. What can I tell you? They gave it to the bald guy. (Laughs)

Cryptic Rock – We know what the bald guy is. Patrick Stewart! (Laughs)

Stephen Macht – Yeah. So what am I saying? I’m telling you that I made some mistakes because I didn’t play the game, and I regret that. On the other hand, I also had a very good career, doing interesting roles that allowed me to muscle around, both in serious stuff on the stage here in California, and a lot of other work.

I’ve really enjoyed it. Even my revisit in the Soap Opera, General Hospital, which came in when it was, I think, in the late ’80s into ’90s. They hired me to do it for six months, and it went on for a year and a half. I had done a soap opera in New York, All My Children, probably six to eight years earlier, when I was out of work. I thought maybe going back to New York, doing a Soap Opera, and then bringing my family back would revitalize my career. I hated being there. I hated doing the work. I looked down on Soap Operas. I thought,” Jesus, what am I playing? I’m playing a psychiatrist whom some madman hired to kill the lead woman’s kid. This is stupid.” This affected my attitude. It didn’t last.

I came back, and I started to study with a great acting teacher, Milton Katselas, who, if you were in the room at the time, I studied with him for about six, eight years on and off, you’d see every television and movie actor known, really good ones, studied with him. Milton was really in touch with the original instinct to become. He would probably be after about three weeks of assignment in scene study, sit you down in front of everybody, and say, “How do you think you did?” I said, “Yeah, eh.” He says, “Yeah, exactly. Yeah, that’s exactly who you are. You’re shitty. Now, do what I’m going to tell you to do.” Most people would say, “What are you talking about?” I said, “Milton, I can’t resist you because way back, I audited a class when I first came out in 1976, and you scared the shit out of me. I got nothing to lose, Milton.” He said, “Then good. I’m not going to kick your ass out because people who don’t want to do what I tell them to do, I tell them get the hell out of my class. Throw a stone. You’ll hit an acting teacher in LA.” He was great!

He would say, “Steve, you know what? You think you know what’s good for you. You don’t. I tell you to do certain parts, and you have an organ reject.” When you say, “I’m not doing that. I can’t do that.” He said, “The moment I see that in an actor, that’s the part you should do. That’s the investigation you need to do. Why are you resisting this? You’ve got to look good?” He told me, “You need to grow in the area and reveal who that is inside of you, because it’s there.” He said, “If you do any part, you’d better know why you’re doing it. What is it about you that you have that nobody else can give? That’s what you’re after. And in every part you do, you are a broken human being. I can see it. You have life in you. You have dark, dark shit in you.” He told me, “I want to see it all in any of the parts that you do.”

So, through a sequence of scene studies he would give me, he’d make me enter in front of all these characters, all these guys and women, 15 times, saying, “You don’t have any reason to be there. Get the fuck back. Open the door and come in with, Are you hot?, Are you cold? Or are you stressed? What are the given circumstances? You must bring that in. He would say to me, “Stephen, you don’t know anything about acting. And you’re studying in England? Come on! You have to set all the given circumstances and personalize them. I don’t give a shit how the characters do. How would you feel if you were there?” I would finally bring something in. He’d say, “That’s it. End of lesson. You did it.” And that extended to everything.

Comes probably four years later, and I get this offer to do a Soap Opera, General Hospital, to play a bad guy. I do it, and I love it. I’m learning 20 pages of dialogue every other day. I also went back to study my Jewish roots and to become a rabbi. So I was studying halftime and acting. I loved it because it forced me to get up to hit every other day and to decide that this script only exists, and this is how Stephen is going to be this guy, Trevor Lansing. There’s no such character as Trevor Lansing; it’s Steven on that day. I loved it. I didn’t fear any of them.

Silently, I knew my instincts to survive were what was at stake. I could joke, and it freed me up. Milton called me, and he said, “Stephen, you’ve never been as good in your whole life.” You’re finally realizing that you are the guy. This character has all of the darkness and all of the lightness, and you make your choices to reveal who you are. That’s you!”

Sadly, Milton died probably six months later. I never went back to study because I was doing all this work. Somehow, through my work and my studies, I ended up in a new place called Yeshiva. I had experienced stuff in my life; I almost died in a car crash, and I was so lucky to get out of it. I just got up every morning doing sort of thank yous. I would meditate, just saying, “Jesus, am I lucky to be alive. In this rat race that’s Hollywood, you’re just lucky. You’d better give thanks.” So every day I would do that. And then, finally, after a year of studying on my own, I went and started studying at this new Yeshiva with Reform Rabbis, Conservative Rabbis, Orthodox Rabbis, all forms.

I studied and really investigated my Jewish roots and how that allowed me to use the dark side and the goodness that was in me. Milton would say to me, as I was doing it, he’d say, “Listen, you’re okay, but what’s going on? You seem conflicted in some of these scenes. You’re not really there.” I said, Milton. Your class is on Saturday.” I was sitting on the edge of the stage, and he was critiquing me. He said, “What’s the matter?” I said, “Milton, you know it’s Saturday Shabbat, I should be in synagogue.” He says, “Then get the fuck out of here. Go to synagogue!” I said, “I can’t.” He says, “Why not?” I said, “Because you’re my rabbi!” (Laughs) He said, “Then be here, asshole!” (Laughs) So, those two sides you can see as I’m talking to you, he taught me how to internalize both of those, the conflicts.

Many of the characters that I do show that. There’s this light side, and then there’s a really devastating dark side. Based on all the losses, all the pain, all the shit that anybody has gone through, but my particular story. I try to bring that to the simplest character. It looks simple on the page. I try to bring that mix of who I am into any character I play. That’s the joy of it.

I just turned 83. The guys my age are being offered for those parts that are open, just being offered. They don’t have to audition; they have a bigger name than I do now. So I’m almost all retired. I had a great time with Suits with my son because the writer, Aaron Korsh, created that part for me. I loved being with him over those. It was really, really wonderful to act with him.

Cryptic Rock – These are all extremely fascinating stories. The definition of the word rabbi is “teacher” or “to teach.” It feels like Milton Katselas was your teacher.

Stephen Macht – He really was my rabbi. He was my teacher. He pressed on that nerve that said, “You can lie to yourself, and you can lie to every one of these people watching you work, but you can’t lie to me because I know who you are. Or I know enough of you to know that you are not revealing who you really are, and you need to go there. He taught me to stop rejecting the organs of these parts and to internalize everything you do, and to allow me to see it – no shame in that. He taught me there’s nothing that you have done in your life that is so shameful that you are not, like all of us, a broken human being, full of great gifts.

Cryptic Rock – That is incredibly profound. You mentioned the mistakes you made when you were younger. We all make mistakes. We are all arrogant at some point. It’s just the way it is. Through those mistakes, you were also very hardworking, from what it sounds like. That is a really great attribute of an individual, no matter what they’re doing in life.

Stephen Macht – I agree. I’m going to reveal some things to you. The major mistake I made as a nine-year-old was that my father died. I went into the reception room at Riverside Memorial in New York before he was buried, and I saw his bald head from the back. When my mother told me the day before that he died, I didn’t think I could survive. I thought I was going to die. How am I going to survive? I’m nine. I looked at him, and I made a decision that I’m going to bring you back to life. You’re not dead. I spent 60 years thinking I could do that emotionally, one way or the other.

As a result, with a lot of men, especially, I didn’t want to fucking have relationships with them. I’d kill them off before they could become my friends. I was overcompensating and playing tough guys and rebels without understanding that I was running away from who I was, a scared kid. I would never acknowledge that. Until finally, I could do that. Milton put his finger on it. And my other rabbi put his finger on it, too. He said, “You never mourn for your parents, your mother and your father.” My mother died. I was married in the cancer room in front of her. I had never really learned to mourn in the tradition that has a mourning process called Shiva, where you sit, and you express the rage, the happiness, the memories, all of it. Nobody really tapped that or brought me to it.

I began to do that later in life. Then I found, as I’m raging and writing all my meditations down, screaming against the world, “You did this to me. You did that to me. That’s why I did this.” All of a sudden, I heard a voice come up and be like, “Who did this to you? Who? You fucking did it.” It broke me apart. At my age, in my mid-60s, to learn that I was responsible for all of it. My father died. My mother died. They didn’t want to. They did. What I did with that was turn it against the world, and ultimately against my anger, was against myself. The rabbi finally said to me, “You’re going to kill yourself. You’d better look at that.”

What I’m saying is my study as a Jew, the PhD that studied the Greek tradition, melded together to say, “We all make mistakes, but the really great people are the ones who take a look at the mistakes and acknowledge their own source in the mistake, discover what they did, and then try in some way to repair it with the people they’ve shit on.” That’s been a keynote of my approach – how did I cause my own suffering in the matter? That’s the story of Oedipus. He did it. He’s got to find out who he is. That’s the process of the play! That’s the process of acting. It is unending your whole life.

Whether I do it as an actor, or I do it as an officiant who buries people, or become a rabbi in funerals, or marry people. When I marry people, I have them answer 10 questions of peace – what was the first sexual ignition that you had? When did that turn into something else besides sexual? What do you complement each other? How do you see your future? What’s funny about each other? They have to answer their own questions. Together, I meld their love story because they each talk about different things that they love and don’t like about each other. There’s a lot of humor in that. The love story is celebrated. That’s what I’m trying to celebrate in myself when I act. What is this love story that’s in you? Acknowledge it. Doesn’t say that I don’t continue to make mistakes. Maybe I catch them a little bit quicker, but at least the process is there.

Cryptic Rock – These are compelling ideas to consider. These are things we start to realize as we get older. The whole idea of self-responsibility and the idea that we blame the world for our problems, never looking within.

Stephen Macht – You contribute to it. What are you going to do to acknowledge your cause in the matter and take an action that does not repeat the error that you made, causing yourself more suffering? Now, sometimes that’s hard to do because you’re going to get a lot of shit from other people, especially in our time now.

Cryptic Rock – Yes, you mention our time and what we are living through; there are an enormous number of narcissistic personalities where people do not want to look inward.

Stephen Macht – The Hebrew word for prayer is Lehitpalel. It means look inside, not praying up there. It is taking a look at what you have done and accepting responsibility. Reverse that and seek what iscalled Tikkun. It’s an active word. Repair who you are and use it to contribute to the world. Some people don’t agree with that.

No comment