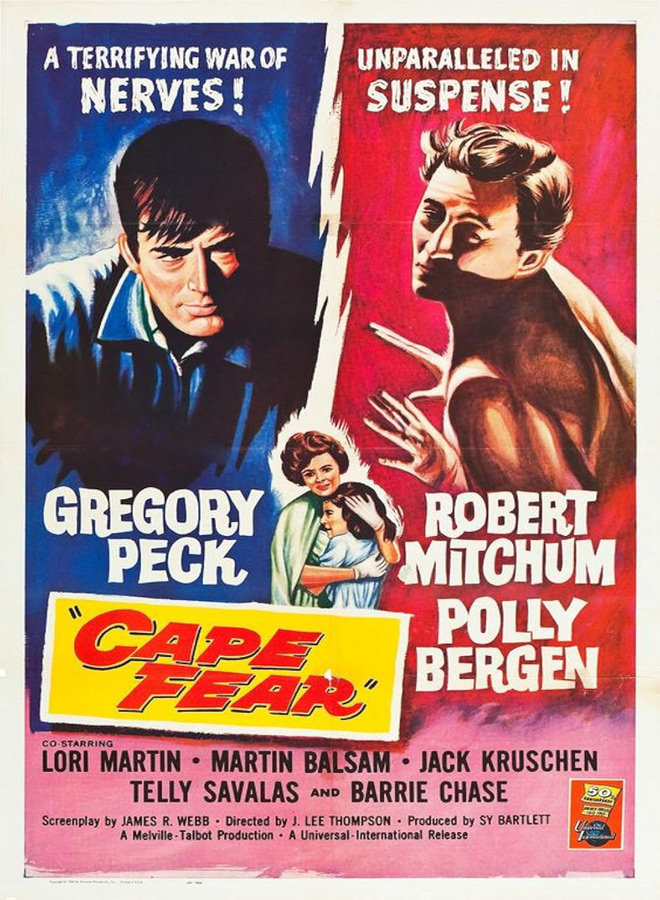

Robert Mitchum’s performance in the 1962 Thriller classic Cape Fear remains one of cinema’s most chilling portrayals of a villain. The battle of wills between ex-convict Max Cady (Mitchum) and lawyer Sam Bowden (Gregory Peck) is timeless because it taps into a simple yet terrifying idea: What happens when the law fails you?

What made this film, directed by J. Lee Thompson (The Guns of Navarone 1961, The Chairman 1969) and based on John D. MacDonald’s novel The Executioners, so ahead of its time was its willingness to explore virtuous complexity. It features a flawed protagonist trying to hide his past from his family and an antagonist whose twisted sense of justice makes his vendetta oddly understood – a rarity in mid-century Hollywood storytelling.

Despite its satisfying conclusion, 1962’s Cape Fear forced the audience to confront uncomfortable questions. So, producing a remake nearly thirty years later was both intriguing and tricky. However, if any filmmaker was suited for the job, it was Martin Scorsese, the man, the myth, the juggernaut, who had an electric vision for reimagining the story.

Scorsese, known for his intense and polarizing character studies, had built a career on celebrating antiheroes (1976’s Taxi Driver, 1980’s Raging Bull, 1990’s Goodfellas). So when he stepped in to direct a reimagining of J. Lee Thompson’s intimate nail-biter – brought to him by Steven Spielberg – it weirdly made sense.

The key to remaking a classic is not simply recreating its plot but rather carrying over its core themes. That is exactly what Scorsese did. By the early 1990s, cinematic culture had evolved significantly. Visceral violence and ethical dilemmas had become more pronounced in mainstream films, and Scorsese embraced both—most notably in the chilling confrontation between Max Cady (played by Robert De Niro) and Sam Bowden’s young female colleague (portrayed by another Scorsese veteran, Illeana Douglas).

While the original Cape Fear remains a taut and suspenseful experience, it is, in many ways, a product of its time. It presents a clean-cut nuclear family and employs a restrained, straightforward filmmaking style. Scorsese, by contrast, took an aggressive and hard-wired approach, reinforcing the idea that an adaptation must deconstruct and reinvent its source material to justify its existence.

Where J. Lee Thompson kept the camera static, Scorsese’s was kinetic – propelling forward, whip-panning, and creating a chaotic energy. While Mitchum’s Cady was quiet and understated, De Niro’s was explosive and hyperbolic. If the Bowden family of the 1962 version were happy and idyllic, 1991’s suburbanites were complicated and fractured.

Martin Scorsese managed to disassemble the original film while also paying tribute to and fully respecting it. He even went as far as to bring in Elmer Bernstein to re-orchestrate Bernard Herrmann’s original composition. He included supporting roles from Cape Fear’s original stars, Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum. “Well, pardon me all over the place” remains among the most underrated line deliveries of the last fifty years.

Cape Fear endures as a timeless story – highlighted by its latest adaptation, which is currently in development for television and features Javier Bardem. The 1962 and 1991 versions serve as distinct interpretations of the same nightmare. The original is a tightly controlled, melodramatic thriller grounded in classic Hollywood storytelling. The remake is an intense Psychological Horror film that delves deeply into moral ambiguity. In the end, both films stand the test of time.

No comment