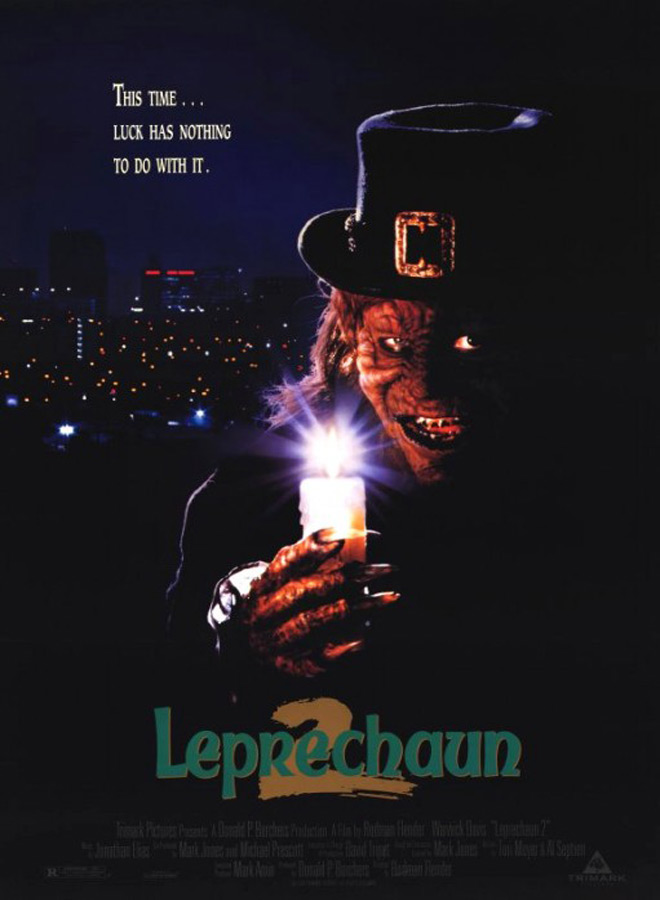

This week in Horror movie history, on April 8th, 1994, the world lucked out and got another installment of the Leprechaun saga. Leprechaun 2 is a truly delightful hunk of cheese, riddled with continuity errors, technical gaffes, and general bush league film-making. The Leprechaun franchise was part of a boom in the Horror genre that stretched the idea of what could be made scary. There were genies in 1997’s Wishmaster and there were puppets in 1989’s Puppet Master. There were bugs and robots and dogs, all personified with rage. There were snowmen with evil and perverted intentions. Anything that was previously deemed innocuous was given a more sinister twist, including those old Celtic ne’er-do-wells, leprechauns. It was a time when horror was synonymous with fun and imbued with a lackadaisical, laissez-faire attitude. Studio pockets were stuffed, so if someone wanted to make a film, say, about a demonic guinea pig, casting started the next day.

As one of the more well-traveled franchise villains, the eponymous Leprechaun visited the hedonistic wonderland of Las Vegas. He rolled up in the ‘hood and liked it so much he went there twice. He even did a space walk in the outer reaches of the galaxy. The first Leprechaun film attempted to be too serious with such an intrinsically silly topic as a murderous leprechaun, but the second film in the franchise struck just the right level of magical absurdity and is rightfully regarded as a fan favorite. Briefly, Leprechaun 2 is about finding love.

In old Ireland, the Leprechaun (known as Lep, henceforth), an iconic role for Warwick Davis (Willow 1988, Harry Potter series), is duly infatuated with a comely Irish lass. According to some arcane leprechaun rule, his courtship of her is dependent upon her sneezing three times without being blessed. Lep’s romantic attempts are foiled and according to another arcane leprechaun rule, he cannot retry for 1,000 years.

By and by, his time comes again and he finds himself in California, preying on one of his original moll’s descendants named Bridget (Shevonne Durkin: The Liar’s Club 1993, Tammy And The T-Rex 1994). He manages to snatch her up after a struggle and spirits her away to his home, a network of roots and tunnels under a tree. However, Lep’s love connection is interrupted when he senses that Bridget’s vapid boyfriend Cody (Charlie Heath: Blossom series, Party Of Five Series) and his shyster-with-a-heart-of-gold uncle, Morty (Sandy Baron: The Out-Of-Towners 1970, Broadway Danny Rose 1984) got their hands on a shilling of his gold in the scuffle. Now, an exchange must be made and Lep is not one to strike a fair deal.

After lawnmower faceplants, whiskey drinking contests, golden weight gains, and go-kart hit-and-runs, the film culminates with a showdown in Lep’s home which apparently “has many surprises.” At length, once again, Lep is explosively defeated. Cody and Bridget go on to be the same carefree, 30-year-old teenagers as they were at the beginning, taking the deaths of a handful of people around them in ambivalent stride.

On its opening weekend, long after the hangover from St. Patrick’s Day subsided and people had moved on to Easter, Leprechaun 2 raked in a pot of gold worth $673,000 and just recouped its estimated budget of $2,000,000 in its entire domestic run, making it a technical success for Trimark Pictures, but it was also the last installment of the franchise to receive a theatrical release. Trimark eventually morphed into the cinema giant, Lionsgate Entertainment, and Director Rodman Flender went on to direct the cult classic Horror film, 1999’s Idle Hands.

Everything about Leprechaun 2 is comically dated to the mid-1990s when the police were passive about their paperwork, subtle racism was business as usual, and phone calls took place within a 5-foot radius in the kitchen. The sets were still intricately and expensively constructed rather than keyed in during post-production which is a rarity in today’s film culture. Keying technology was only in its fledgling form, but was used, albeit briefly, in Leprechaun 2 when Lep forms an illusion to trick Cody into giving him the shilling. The effect is clearly digitally augmented and identifiable to today’s technologically spoiled eyes, but in 1994, Warwick Davis and the production of Leprechaun 2 were settlers on the rugged frontier of computerized movie magic.

Much of the set lighting was also conceptually adventurous and open to interpretation. Lep’s labyrinthine underground domicile was brightly and evenly lit, despite being under a tree in a magically-adjacent dimension that there is no clear escape from or power grid to. Blame it on magic.

In addition, an entire room of Bridget’s house was lit with an inexplicably bright red light that was appropriate to nothing. It did not create an atmosphere; it just made everything a supersaturated crimson; the reason went unaddressed. Multiple sequences of Leprechaun 2 prompted audiences to laughingly scratch their heads, wondering what the lucky green hell possessed the production to make the endearingly awful choices they made.

All of its technical faults, it is preposterous acting, and flimsy writing have, over time, crystallized Leprechaun 2 into the lovable Horror-Comedy it is today. It is so awful that you want to hug it. It is a bad film, assuredly, but for those who can appreciate the corniness of a bygone era of cinema, it is inexhaustibly entertaining. When a film is so bad, yet so loved, at what point does it stop being bad? Leprechaun 2 represents a feeling from the 1990s that moviegoers today have forgotten or perhaps never known: going to the video store, walking to the Horror section, and seeing a wall of cheeseball movies, knowing that they are going to have fun.

No comment