In Western society, women are trained, practically from birth, in the ways of femininity. Throughout life, they are groomed to attract a mate while simultaneously being warned away from the members of the very population from which mates are traditionally found. They are told to beware: he only wants one thing. Then they are told just how to get him to want that one thing from them. The conflicting messages makes it a difficult world to navigate, and it takes a conscious effort to break through the expectations and restrictions imposed on women and to see them and men not as entities intended to fit into neat little gender stereotyped boxes, but as the complex, varied, mutable human beings that each are. Women might still retain the exterior trappings of a chosen gender identity in order to function in a society that favors tradition, but they acknowledge that their gender, in truth, is largely inconsequential. Still, it would be foolish to ignore the fact that some men do want to harm females. Gender identity and the significance society places on it force one into a game that is complicated, delicate, exhausting, and sometimes dangerous. Now imagine being thrust onto the playing field in the middle of the action without any preparation. That is just one of the complicated topics Sci-Fi film Under the Skin explores.

- Still from Under the Skin

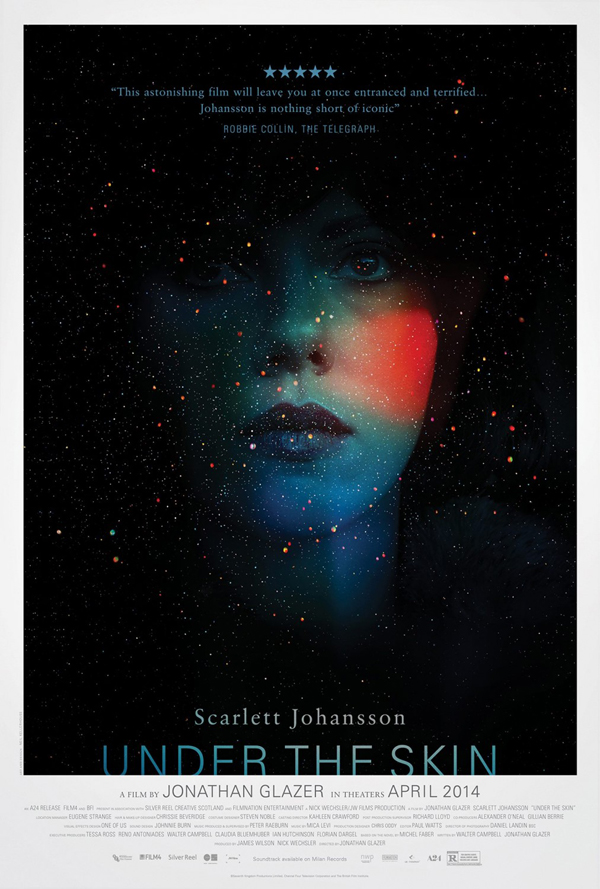

A Jonathan Glazer film, released in the US in 2014, Under the Skin is loosely based on the 2000 Michel Faber novel of the same name. It raises questions concerning identity, and with a female protagonist (Scarlett Johansson) who preys — literally — on men, it would be remiss to ignore the messages that are present concerning gender identity specifically. It is important to note, though, that Under the Skin does not take sides in any specific political or social debate. It will contain a different message for every viewer, and those messages are not heavy handed or pedantic. The film simply explores these ideas, raising questions meant to be considered, not settled with a decisive response, inviting the viewer to arrive at their own conclusions.

A quiet film with little dialogue, the narrative surrounds “Laura,” an alien being disguised as a beautiful woman who is sent to earth to harvest the skins of men whom she lures into her trap by means of seduction. It is unclear why she needs to do this — the novel answers this and other questions, but the film is too far a departure from its source to really compare the two — but Laura’s growth as a character is more important than the narrative itself. At first she is utterly indifferent to the human beings surrounding her as she drives aimlessly through the streets of Scotland. In unscripted scenes involving not actors, but authentic passers-by, she makes intermittent stops to ask young men for directions in an effort to find proper victims (i.e., ones who would not be missed). As the movie progresses, Laura gradually changes, and the narrative traces her evolution from blasé predator to something more closely resembling a human woman, as Laura first experiences empathy, then shame, and finally, fear.

- Still from Under the Skin

During the first half of the film, Laura’s detached cruelty is chilling, particularly when the fate of her victims is revealed in a surreal scene depicting what takes place “under the skin” of the mirror-like liquid into which her prey willingly submerge themselves, beguiled by the naked beauty beckoning them forward. By the time she picks up a man with a facial deformity (Adam Pearson), the viewer is overwhelmed with pity, perhaps compensating for the human emotions that the protagonist lacks, and the scene between her and this dubious, yet earnest gentleman is tense. In the car, Laura asks the man a series of invasive questions and then compliments him on his hands. She appears utterly clueless as to why the man prefers to do his grocery shopping by dark or why he does not have any girlfriends. The man is clearly bewildered, reluctant to believe that such a beauty desires him, but he does not resist. It is this encounter that marks a turning point for Laura, who catching her own arresting reflection in a mirror, becomes distracted, absorbed, and disoriented. It is as if confronted by the only human aspect of herself, that is, the outward appearance, she now wants to explore what it means to actually be a human. With a newfound awareness of humanity on both a conceptual and physical level, she becomes more observant of herself and others. In one particularly memorable scene, Laura stares into another mirror, naked, flexing various muscles, observing bone structure, enamored of the human shape and, possibly more so, its mechanics.

- Still from Under the Skin

After Laura’s initial encounter with her reflection, the tone of the film changes, and in an abrupt but believable reversal of fortune, she becomes unsure of herself and vulnerable. After so much time playing the part of a seductress, she learns how complicated it is to actually bring seduction to its natural conclusion. She learns about the desires and fears humans conceal “under the skin.” She learns how magnificent the female form is, and, ultimately, how dangerous it can be to inhabit that form. While she revels in the female body as it appears in the mirror, when confronted with its intricacies and secrets, she is mortified and weakened, and suddenly, it seems as if everyone is a predator, and now she is the prey.

Regarding plot, Under the Skin is fairly simplistic, but in leaving out details and abandoning exposition, it prompts the audience to examine the subtext, and there is certainly a lot to uncover. The film invites viewers to explore the human experience from the perspective of an outsider, and in doing so, it highlights both the beauty and the disorder inherent in this life. Even though it is quite distinct from the novel on which it was based, it is a decidedly literary film, and those who prefer a more straightforward narrative will be frustrated with Under the Skin.

Those who do not mind putting a bit of work into a viewing experience will appreciate the artistry of Under the Skin. Atmospheric and richly colored, the film conveys Horror in the context of beauty. Use of sound is thoughtful and deliberate, and in scenes where Laura is alone, the silence is almost excessive, reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s version of space in 2001: A Space Odyssey. In contrast to the pristine quiet of those moments, when Laura finds herself in a crowd, the sound is jarring, with an exaggerated Doppler effect, voices rising and falling in pitch and volume as the messy human world rushes past her. In one scene, where the viewer is presumably seeing through Laura’s eyes, it appears as if she sees the world kaleidoscopically, colors melting together in a chaotic sort of beauty. The sensory overload emphasizes her position as outsider and her loneliness, while also reminding viewers that the human experience is neither easy nor tidy. The complexity of that experience is what makes it interesting — so much so that it can seduce a cold and ruthless alien being into risking its life to seek the meaning and mystery of the soul that is so craftily hidden under the skin. CrypticRock gives Under the Skin 5 out of 5 stars.

- A24 Films

No comment