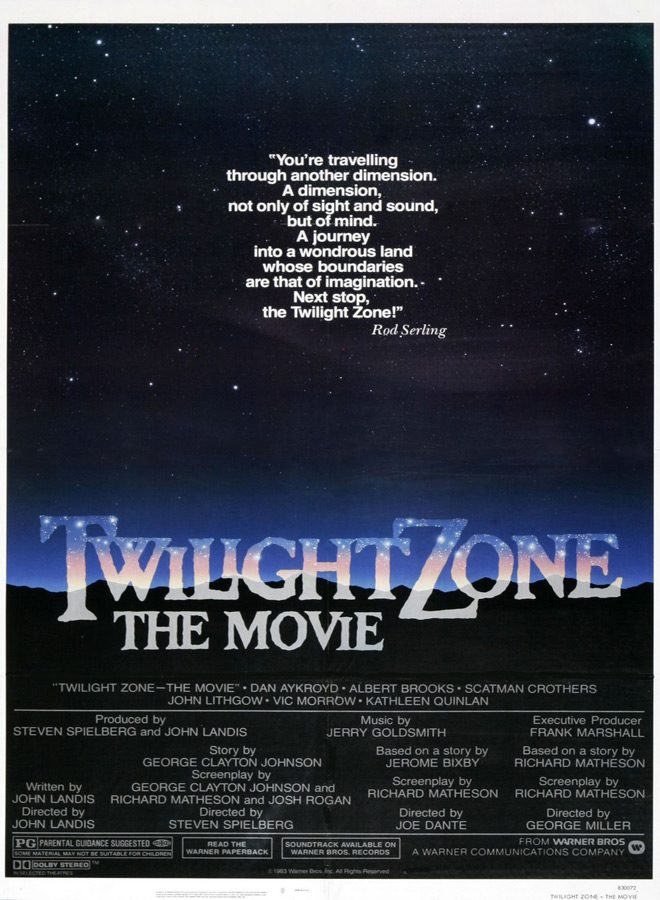

This week in Horror movie history, back on June 24th of 1983, the silver screen took viewers at last to a place beyond sight and sound with Twilight Zone: The Movie. The Twilight Zone had been a popular television series for decades, created and narrated by the inimitable Rod Serling, and fans were eager to see what a big-screen adaptation would look like? The result? A troubled production that was just what some were looking for…and a grand disappointment to others. Either way, it is impossible to claim that Twilight Zone: The Movie did not stake out a claim on movie history.

It was an obvious question posed to the creatives in charge, but that did not make it any simpler to answer; how does one produce a feature-length adaptation of an anthology series? The show had no recurring characters besides a narrator, no larger storyline, nothing that could be taken as its essence and expanded upon. Indeed, the only thing common to each of its stories was its style – The Twilight Zone was not a brand because it established a universe, it was a brand because it established and stuck a unique tone and a particular narrative structure. The tone was one of light Sci-Fi dread, and the structure was that of escalating questions that reach their apex in a moment that twists everything one thought they had known about the said story on its head.

Did they take one famous story and expand it? Write an entirely new feature length story? Try to form a mythos out of the stories laid down already? The answer was quite a bit more pedestrian: the movie would simply be a number of different and mostly unconnected segments, like several episodes of the show strung together. Even further, three of those segments would be remakes of popular previous episodes, making this movie far more of a Twilight Zone mix-tape than an original EP.

To make Twilight Zone: The Movie even more reminiscent of the show, the decision was made to hire four different directors, one for each segment. John Landis (Animal House 1978, American Werewolf in London 1981) and Steven Spielberg (Jaws 1975, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 1982) each directed one segment, additionally acting as producers who stewarded the project through development, while George Miller (Mad Max 1979, The Witches of Eastwick 1987) and Joe Dante (Gremlins 1984, Innerspace 1987) also got a chance to flex their cinematic muscles.

After a brief prologue, the segment Time Out opens the film – the only segment that is not a remake of a previous episode from the television show. Its placement is clearly intentional, frontloading the film’s creativity to draw in an audience both new and old before segueing into a walk down memory lane. Kick The Can, It’s A Good Life, and Nightmare at 20,000 Feet follow, reconstructing some infamous episodes of the old television show to mixed effect. The rise in production quality is clear throughout, but as some critics pointed out – was it worth all the effort? The film did little to significantly add to the existing stories.

Ultimately, however, it is not the quality of its substance that will forever mire the film in controversy, but rather the details of its production. During the filming of the film’s original segment Time Out, tragedy struck during a stunt involving a helicopter. The actor, Vic Morrow (B.A.D. Cats series, Charlie’s Angels series), along with child actors, Myca Dinh Le and Renee Shin-Yi Chen, were killed when choreographed explosions caused the helicopter to spin out of control, crushing the three and ultimately killing them.

The incident rightly cast a dark pall over the rest of the film’s production and eventual release. Things did not improve for the crew when the details of the incident became public and it was revealed that the two child actors should never have been on set unsupervised at night in the first place, as it was a breach of California’s stringent child labor laws. Landis, the director of the sequence, and several crew members under him, were eventually tried for manslaughter in a case that lasted for years, eventually being acquitted. They were deemed not guilty in the court of law, however, the same was certainly not true for the court of public opinion, as the incident drew widespread attention to Hollywood’s routine skirting of state labor laws.

Despite all this, Twilight Zone: The Movie was still a financial success and many would say was enough for CBS to give the green light on the 1980s television version of The Twilight Zone which aired for 3 seasons. In addition, it received eight film nominations, and talented Actor John Lithgow (Footloose 1984, 3rd Rock from the Sun series) took home the Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actor in 1984 for his role in the Nightmare at 20,000 Feet segment.

Twilight Zone: The Movie was received with mixed reviews, and to many, its substance could never rise above the controversies of its construction. For this, it has become a disturbing footnote in Horror movie history – an example of an industry’s dark side driving people to a fatal end, made ironic by its attachment to a franchise that always reveled in stories of the same timbre.

No comment