Generational divides have likely been a thing since the Stone Age, though it has seemed particularly pronounced in the past decade or so. Boomers complaining about millennials, millennials complaining about boomers, boomers confusing zoomers for millennials, and Gen Xers wondering why their grandkids are called ‘zoomers’ instead of ‘Gen Zers.’

The divide is universal too. In Japan, 1988’s Akira had some very ’80s-looking biker youths in the future turning their noses up at the old order while getting caught in their schemes. In the same year, Isao Takahata (Only Yesterday 1991, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya 2013) adapted Grave of the Fireflies for Studio Ghibli with a sentiment that judges youngsters for disrespecting their elders.

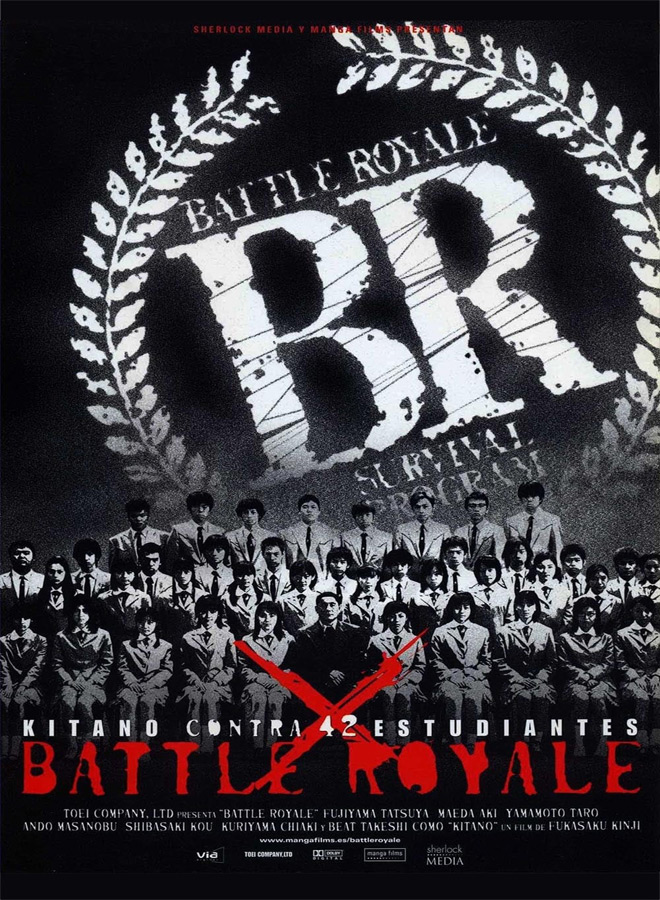

Then, on December 16, 2000, Japan got another generational battle in Battle Royale. In the near future, the Japanese Government takes extreme measures to curb the increasing rates of juvenile delinquency through the titular Battle Royale Act. High school classes are randomly selected to a three-day stay on a deserted island where they are forced to fight each other to the death. Those who refuse or try to escape are killed by explosive trap collars on their necks. The last one left standing gets to go home alive.

The film has Shuya (Tatsuya Fujiwara: Death Note 2006, Kaiji: The Ultimate Gambler 2009), Noriko (Aki Maeda: The Cat Returns 2002, Motherhood 2019) and their classmates in the latest Royale, overseen by their sadistic teacher Kitano (Takeshi Kitano: Hanabi 1997, Zatoichi 2003). Neither Shuya nor Noriko want to kill, but is it their only choice or is there another way out?

Directed by cult film director Kinji Fukasaku (The Yagyu Conspiracy 1978, Battles Without Honour or Humanity 1980) and written by his son Kenta (The Challenge 1982, XX 2007), the film gained both acclaim and notoriety. It became one of 2000’s highest-grossing films in Japan, while also being condemned by the National Diet for its controversial content. Fukasaku fought against its R15+ rating, as he aimed the film towards Japan’s teens. Ultimately, he gave a press statement telling teenagers “You can sneak in, and I encourage you to do so.”

The controversy continued westwards. Neither America nor Canada received an official release of the film until 2012 via Anchor Bay Entertainment. Eager film fans had to either import it, catch it at select film festivals, or use the internet. Part of this was due to unfortunate timing, as the Columbine incident was still a fresh memory in 2000. Mostly, despite content worries, the biggest obstacle was legal and corporate red tape between distributors and the film’s owners, Toei Company.

Not that it was the only bloody, violent film around. In fact, it seems quite tame compared to some rival pictures. 2001’s Ichi the Killer had stomach-churning scenes that only stopped short of featuring literal stomach churning. In the same year, Suicide Circle drained the artificial blood tanks dry with acts of mass suicide. It courted the same kind of controversy as Royale with high schoolers committing carnage, inly it was against themselves rather than each other.

Yet Battle Royale hit more bases worldwide. How come? It could be because it was based on a novel of the same name by Koushun Takami (Cold Blood 2004), which gained a similar buzz of fame and infamy worldwide when it was published in 1999. The book added the extra wrinkle of being set in an alternate world where Imperial Japan successfully took over East Asia. Not only was it criticizing the Japanese government, it was criticizing a regime some people still treat too lightly.

The film excised these elements, and as a result might have made it more readily accessible to audiences outside of Japan. It leaves Royale with the more general theme of the rising youth vs. incumbent elders. The younger generation have always felt the older generation rarely know or care about their troubles, and Royale makes that sentiment literal; they really do not care about them unless they can be forced to play by their rules.

So one could call it the first film to show boomers vs. millennials. Yet, while it certainly looks like it is from the 2000s, it is not limited to that era; zoomers can see themselves in the schoolkids as much as wistful millennials do. Meanwhile men and women can generally relate to the individual mini-plots that link the cast, like Kitano dealing with his indifferent daughter over the phone, or Takako (Chiaki Kuriyama: Kill Bill Vol 1 2003, Blade of the Immortal 2017) coming off worse for wear after refusing a classmate’s advances.

Battle Royale is not exactly subtle about its themes, nor does it go as in-depth into them like other intergenerational dramas (see 1953’s Tokyo Story). However, the film has more going on under its hood than its reputation suggests. It is not just fun time schlock for schlock’s sake, but a drama about human nature wrapped in an action flick wrapper. That still might make it a hard sell for the particularly squeamish or non-violent, though if they feel particularly daring and give it a go, they will find a purpose behind the bloodshed.