Taking shape in the early 1980s, Minneapolis, Minnesota-based Information Society traveled a long and interesting road to success. Combining elements of a list of genres ranging from Synthpop, to New Wave, to Freestyle, to Techno, plus more, Information Society brought with them a forward-thinking approach to music. Beginning to break into the mainstream with the single “Running,” they reached massive superstardom in 1988 with #1 hit “What’s on Your Mind (Pure Energy),” resulting in their self-titled major label debut striking gold status. Continuing to push the envelope into the late ’90s, Information Society decided to take a bow in 1997, ultimately ending the story of the band. Thankfully, close to a decade later, they reemerged and once again re-invent themselves, thus making them a distinguished and important part of Electronic music in the new millennium. Recently we sat down with Lead Singer Kurt Harland Larson for an in-depth look into the the history behind Information Society, their latest album – Orders of Magnitude, the changes in the music industry, and much more.

CrypticRock.com – Information Society, it began almost 35 years ago now. In that time, you have attained a series of highly charted singles, released seven studio albums not including the most recent one which just came out, and you have continuously toured. First, we want to ask you, what has this magnificent journey been like for you?

Kurt Harland Larson – It’s been so many different things over the years. Orders of Magnitude, which came out in March, is album number nine. Whenever I try to summarize the band’s history experience, I have to divide it into eras. Broadly speaking, it’s been five different things, and each of those had completely different experiences for us. When we began, we were 19 year old college students, well I was 18 when we started, but our first year we were generally 19, going to college in Minneapolis just playing some local shows. During that time, which in many ways was my favorite time, we didn’t know much of anything about the music business, which looking back on it was kind of nice. We mostly were trying to create and explore and occupy a kind of conceptual space that was expressive of, what was for us, our social, global, geopolitical outlook. We were heavy with references to Orwell and lots of social political commentary, most of which was aimed at the fear of totalitarianism. Of course we were all born in the early ’60s, which means we grew up with the constant fear of nuclear war, that was a big part of it too.

The other big thread for us was a sense of humor; half the time we would be thinking about what would be good musically or performance-wise and the other half of the time we would be thinking about what would be funny. For example, we chose the name Information Society because the term had already sprung up as a description of the economic and social movements to come due to advances in computing technology. It seemed like the right way of capitalizing on the popularity of that term. We also chose it because it also sounded very much like INGSOC. If you abbreviate Information Society to INSOC, it’s almost the same as INGSOC which is the NewSpeak word for English Socialism in Orwell’s book 1984.

CrypticRock.com – That is quite interesting. Now that you bring that up, the reference to Orwell’s 1984 is quite clear. Did you have high expectations for the band in those early stages?

Kurt Harland Larson – We didn’t make much of any money, and we didn’t expect to. What was important to us at the time was making a sort of visual, aural, and performance statement. Developing a kind of brand that was our own, we were the only all live, all electronic Pop band probably within 400 miles of where we were in Minneapolis. People literally did not know what they were looking at when they saw us play. There’s a certain gratification that comes with that to a bunch of very young people who pride themselves on being weirdos. It was really fun to have people come in and look; they would hear it and say, “This is music and you can dance to it, but what are those black boxes? How are those sounds being made?” It’s not like now when everyone is very used to electronically generated sound; people would hear those sounds and just think, “I’ve never heard a sound like this in my life, what in the world is it?” Which is a very polarizing thing of course, some people love that experience, they like hearing things that they haven’t heard before for which they have yet no context.

Other people find that very unsettling; like, “I don’t understand. I don’t see anybody playing a guitar. I don’t understand what it is. I don’t know how that sound is made. I don’t like it.” We got very little in the way of lukewarm responses; people either loved us or hated us. We were pretty socially isolated because the music scene at the time was primarily all about creating a Minnesota version of the Punk Rock explosion that had happened several years earlier in Europe, and it was happening at that moment in California. In many ways, it seems to me like it was the precursor to what became Seattle Grunge, in every way totally the opposite of what we were doing, which was one part of assertive performance theater, one part Dance music, one part Experimental Electronic. It was what bands typically find when they are really young and just starting out and not really making any money yet; it was fun, difficult, worth it, not worth it, and ultimately very memorable. That’s just the first of 5 phases. I don’t know if I’m going a little too deep on this one for you, but there’s a lot of information here.

The second phase started when we had, for various internal reasons, people changing their lives and moving, wound down and we were doing a lot less with the band. Paul and another local artist from another locally Electronic band had created a single in the studio called “Running.” It was actually written by our friend, that was Murat Konar, despite the name, he was just as American as we were. He grew up in the next suburb over from us. His parents had come from Turkey, but he himself grew up in Minneapolis with us. Paul had developed his interest in studio recording,but they really weren’t expecting anything to come of it. Through a lot of just blind luck, that one song was chosen by a publisher of Wide Angle Records, he wanted it to be part of his record pool. Do you remember record pools?

- Independent

- Twin/Tone Records

CrypticRock.com – No, please elaborate.

Kurt Harland Larson – Because of changes in technology, record pools don’t exist so much anymore, but the basic idea was that in the ’80s, if you were a DJ and your genre was Contemporary Dance music, it was both very important and difficult to stay very current to anything new that was coming out. A DJ would subscribe, for rather a lot of money actually, to a service which would bundle together some number of pieces of vinyl, like 25, 50, 60 pieces of vinyl each period, maybe a month or quarter or something, and mail them out to you. You get this big box of records, it would be a bunch of stuff that had just been published in the last few months. That way DJ’s were able to get the jump on the market a little bit, it was a big advantage for them. That song that Paul and Murat did, called “Running,” got put into Wide Angle’s record pool, which is actually how they made a lot of their money. They had a record store, they had a record pool and the actual printing and publishing of records was the least profitable. Because they wanted to sell their own records, they put a lot of his own records into his record pool.

The record went out there and we thought, “Whatever,” especially at a time when no one anywhere had never even heard of us, that was a big deal. That song, “Running,” by sheer luck, happened to become extremely popular with club kids in the Bronx and Miami, and to be more specific with Latinos in both markets. Puerto Ricans in the Bronx and mostly Cubans and other Caribbean islands in Miami. We didn’t know this scene existed but there was this thing they did called Track Shows where they’d be having a dance night, the DJ’s are playing songs. Nobody was really interested in seeing a band come in and perform a concert, but, if you could get the person who sang that one song that they play every night to do a live performance of it in just 5-10 minutes then that was entertaining. People kind of enjoyed that. So we’d get paid, what was for us at the time, age 23 or so, pretty good money to come out and perform 2 or 3 songs. It was super easy and for college kids, pretty lucrative. That began the next part of our career.

CrypticRock.com – What was that next part of Information Society’s career like?

Kurt Harland Larson – It was pretty difficult for me. It was hard for us to adjust because all of our original avant garde assertive performance art aesthetic just completely didn’t communicate to the audiences in this new market. They had no idea what we were thinking, doing, or talking about. They just wanted to hear the song that they liked and they wanted to see someone sing it live. Most of the Track Show acts were just one or a few people on microphones and nothing else. They would sing along to a version of their song that didn’t have vocals on it.

We started out thinking that it was really important that we play a lot of instruments, which in hindsight helped us kind of differentiate our act and upped our price a little bit because no one else was doing that. That made it more of a spectacle on stage. I wasn’t very comfortable with the fact that neither the audience nor we could relate to each other culturally; they didn’t get us as people, we didn’t get them as people. They loved our song, we loved their energy, not to mention their money, but it was kind of like feeling you aren’t really of their people and they aren’t really your people. While that can be fun, then it becomes month after month, feeling like you are out of place. It’s artistically and personally disorienting, and a little emotionally tiring. That was actually kind of hard for me, I think Paul adjusted to that better than I did.

CrypticRock.com – That can understandably be a bit of a stress on some people.

Kurt Harland Larson – As a result of all that activity, there was a label in NY called Tommy Boy who specialized in Club/Dance singles printed on vinyl, who wanted to pick up that song, “Running,” and print it. So they bought it, the right to print it from Wide Angle in Minneapolis and put out their own version of it with a remix by a guy named Joey Gardner and a bunch of other remixes followed including one by Little Louie Vega. Joey Gardner did a great remix that is the version that became the most popular and most well known. I’m pretty sure it was a somewhat altered edit of his mix that got published on our first Warner Brothers album that came a bit later. Tommy Boy then got half purchased by Warner Brothers, meaning that Tommy Boy was keeping the singles but Warner Brothers could option any of their acts to albums. We caught the eye of a few people at Warner Brothers and they decided to option us to do a new album. We spent a long time recording a new album where there were various travails of that.

Again, getting back to your original question, what was it like, this was probably the strangest period of our career. There was a great deal happening all around us and about us and with us, we understood it very poorly. It was our introduction to the music business and now I realize it was one of the strangest ways to get into the music business that I’ve ever heard of.

When we recorded our Warner Brothers album, that started to bring us back into something that was a little easier for us to understand. This was being run from Los Angeles, it was being run by a broader cultural cross section of the US, so it wasn’t as focused on specific Puerto Rican Bronx or the Cuban Miami niche. We began to feel like we were getting our bearings a little bit better making that album. I’d say when that album was released in the Summer of ’88, when the single of “What’s on Your Mind” was released and the video for it was put on MTV, that marked the boundary into the 3rd phase, which is our Warner Brothers days.

CrypticRock.com – What were those Warner Brothers years like?

Kurt Harland Larson – We put out 3 albums on Warner Brothers. That was the period that we were actually able to make a living off the band, we were kind of eking by before that. The only reason we were surviving was because we were really young kids with low expenses and getting by on almost nothing with no responsibilities. If any of us had had a family, a mortgage or something, it never would have worked. Almost overnight, we went from relatively impoverished obscurity to getting a lot of attention, even public attention. We started to get recognized and that was again very disorienting, and we all reacted to it differently. I found it frightening and unsettling, it made me kind of nervous and paranoid. Paul, who has always been really good at managing his career, immediately started learning how to capitalize on the attention to create career opportunities for himself.

We pretty quickly all moved out of Minneapolis and to New York. We’ve been spending a lot of time there doing the creation of the album, which was recorded in New York, and we had gotten used to being there. Tommy Boy was there and we thought it made more sense to live there, and so we lived in New York for 5 years; the heyday for us. We put out a Warner Brothers album in 88′, 90′ and 92′, every 2 years we had this cycle going – recording, publishing an album, touring, writing new songs, and doing it over again. That was a pretty good time. We had the resources to live a little less desperately; we could actually pay rent. That’s when I had a 1 bedroom apartment for $450 a month; that was really cheap, even for back then. My second apartment was $1,300, which was astonishing at the time. I couldn’t believe I was paying that much in rent.

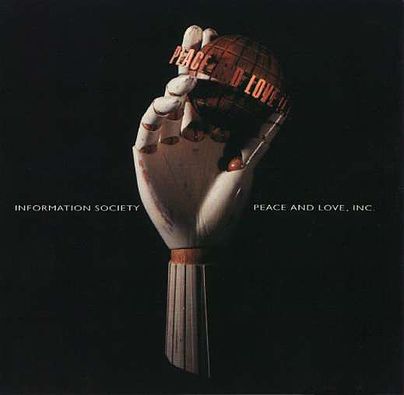

- Warner Bros.

- Warner Bros.

CrypticRock.com – Wow, the prices have skyrocketed even more since then to live in New York City. Tell us more about the varied feelings you had being thrust into the public eye.

Kurt Harland Larson – That was also strange and difficult because as we started to obtain a bit of celebrity, we got all kinds of attention that, again, we did didn’t really understand. Something people don’t generally think about when they think about the concept of fame and celebrity is people don’t have any good instincts evolved into our genome for dealing with situations in which you are confronted by a mass of strangers who all think they know who you are, and you don’t know who any of them are. There’s nothing in the early history of our species that would prepare anyone for that. It’s really unnatural and it can be very unsettling. I find it really difficult, I tended to withdraw a lot and act out a lot. I had great difficulty with meeting fans and behaving nicely towards them. I would tend to just freeze up and act weird. It was not pleasant for anybody, but we got through it. I liked the freedom, I think that period was marked with the greatest amount of freedom that we were making enough money to get by, but we still didn’t have much in the way of responsibilities. We all did a lot of traveling and doing whatever the heck we wanted, that’s when I made that car that you’ve probably seen or heard of.

CrypticRock.com – Of course, that car gained a lot of attention through the years.

Kurt Harland Larson – I bought it in 87′ but I didn’t start really beefing it up till 89′. That was also when I started going to South America, which was even weirder. That was like the whole going to the Bronx for the first time experience magnified by 10, cause that was culture shock beyond anything that we ever dreamed could exist. We were considered to be 10 times as famous there than we were in The States, so it was 10 times more uncomfortable. We made a lot of our money down there. The culture shock and the strange isolation because there are too many people trying to pay attention to you was really hard for me to take. In the middle of ‘93 that all unraveled, the major labels were realizing that the only thing that anyone could really sell anymore was Rap and some flavor of Grunge Rock. You could sell say, MC Hammer, Public Enemy, Pearl Jam, or Nirvana, but it was becoming very difficult to sell things like Nia Peeples, Information Society, The Human League, and things like that. The label dropped us. Paul, who had briefly gotten married, discovered that he was going to have a kid. Paul decided that he was going to stop doing the band thing, move back to Minneapolis, and go back to school. Jim did similar things. I decided to keep the band name and keep doing shows, but drastically changed the direction.

CrypticRock.com – Yes, that was quite an interesting time in the band’s history.

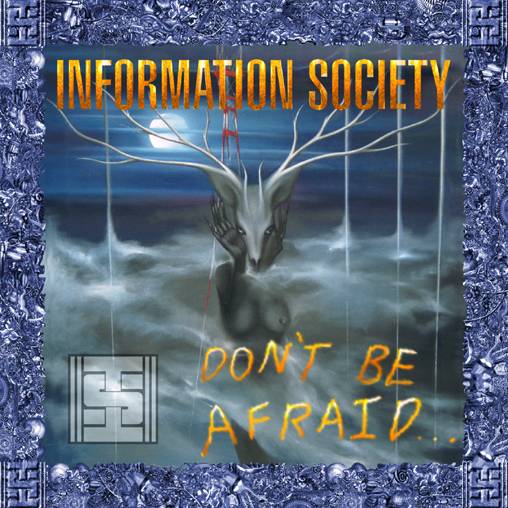

Kurt Harland Larson – The forth phase was the Kurt doing it by himself phase and I took the music style to where I wished we had ended up all along, which was more Goth Industrial. There’s an album I released in early 97′ called Don’t Be Afraid. I don’t know if you’ve heard it, but it sounds nothing like any of our Warner Brothers albums. It’s very harsh and experimental, a cross between Foetus, Kraftwerk, Nine Inch Nails, and Peter Gabriel; something with a lot of really harsh and difficult listening aspects. It’s an album I’m very proud of. I kind of knew all along it would only be valuable to a very small niche of people.

I kept on playing shows, but the interest was waning as I tried to change careers to a different genre. At the same time, I was starting to get more into doing music and sound effects for video games. I got to a point in ’98 where that was paying more than the band was paying and I just said, “Well, you know, at least I am more happy to take this job at the video game company than I would be to continue to put all my attention into being a recording artist.” There’s a lot more dignity to having a real job than negotiating with people about whether you can play their private party at their night club and you come in and do 1 song on a microphone because it’s that hit that we all like.

CrypticRock.com – Completely understandable. So what was it like working with video games?

Kurt Harland Larson – I was doing a lot of music for games that I found to be as or more artistically gratifying and personally satisfying than the stuff that I had been doing with the band, I really had no qualms to really putting that down. From the end of ’98 to sometime in ’04, nothing happened with the band at all. That’s when we began the current era, which is the post trying very hard era. By ’04, all 3 of us – Paul, Jim, and I – had for real grown up careers and some degree of family responsibilities. Paul had 2 kids who were young teenagers at the time. I had just gotten married and we were planning on having kids real soon. Jim was going to college and had just gotten married around that time. Paul, for reasons that are still a bit opaque to me, really wanted to try doing the band again. He resurrected some of his old songs, came up with a few new ones, and talked to me about doing it again. I considered it, but by the time I had gone over everything in my mind, it didn’t seem to add up for me. I turned him down and he located another singer, a guy named Christopher Anton who worked for them for awhile. There came a point, I don’t know when exactly, probably ’06 or so, when they were running into trouble with that line up and Paul asked me to fill in for a few shows, and I did.

- Warner Bros.

- Cleopatra Records

CrypticRock.com – How did that all transpire?

Kurt Harland Larson – It’s weird how this happened. He said, “Christopher Anton can’t do this show and he can’t do that show, can you fill in?” I said, “Alright, I’ll fill in for you. You are my old friend, I’ll help you out.” I made a little bit of money, not that I particularly needed it, but whatever. Then he says, “Ok, I booked a new show for us to do.” I’m thinking, “What, wait, a new one?” I called him up and said, “I said I’d fill in, but I didn’t say you could book shows that I had to do.” We wrangled over that for awhile, but eventually we agreed as long as it wasn’t very often, didn’t take up too much time, and as long as I didn’t have to do things that I wasn’t willing to do, then I’d do the occasional show. Paul had released the album Synthesizer in 2007 with Christopher Anton as the lead vocalist. That album has a shred of vocals of mine on it, maybe one song, and a tiny bit on a second song. We toured around doing some of the older songs and went with Synthesizer for awhile. It was ok.

In ’07, we did what was probably one of my favorite shows I’ve ever done in Philadelphia; one from which we released a live DVD. That really got us all jazzed again to keep doing it. That’s pretty much how it’s been since then. We acquired our new manager Jason. None of us are looking to make this our full time job again, mostly because we don’t think we can. I just don’t think there’s enough interest in Information Society out there to pay for 3 full time lives of people who have mortgages, high rent, children, and other financial drains. There just isn’t enough money to be made for all us to “do the band man” full time. There’s enough for it to be a good supplemental income, and we’ve found ways to pick and choose things are going to be fun.

One of my guesses is that Paul wanted to do it again because he missed the opportunity to travel and the opportunities to meet people in weird, different, interesting situations, and a little bit of unpredictable adventuring in life. Flying to San Paulo and Rio for 5 days to do 2 shows isn’t exactly going to change your world. It’s not Marco Polo’s journey to the Orient, but I’m guessing it’s a little more enriching than going to your office for that week again, like you always do.

CrypticRock.com – Right, it should be about doing it for the love of it. With that said, Information Society has kept going.

Kurt Harland Larson – In 2010 or so, Paul said, “Let’s make another album.” By this time he wasn’t working with Christopher Anton anymore, and I was into that. We made the album that came out very slowly, an album that came out in 2014 called _hello world. I was really pleased with that one. I think, at that time, it was the best album we had done to date, at least in terms of how I feel. Also the process was more collaborative than anything we had done before; Paul and I had siloed ourselves into separate processes before that, we didn’t really work together on songs at all. This time, we hit upon a formula that worked for us; for some songs he would make the recording with all the instruments and send it to me with no lyrics and no melody. I would come up with lyrics, melody, and vocals. I think it produced some good results on that album. We liked that process, so we did another one relatively quickly, ‘Orders Of Magnitude’, which is an all covers album.

CrypticRock.com – Yes, and Orders of Magnitude came out in March of this year. What was it like doing a covers album?

Kurt Harland Larson – Doing a covers album is super fun and super easy because you don’t have to worry too much if this is a well-written song or not, cause it probably is, and it doesn’t matter and everyone knows this is just your interpretation of someone else’s song. Since we picked all the songs that we loved from that particular time span, from the mid ’70s to the late ’80s, we knew we’d love the songs, and they were all fairly well known songs anyway. Really easy, really fun, and again, I think this album is the best one we’ve done so far, to my mind.

The big triumph for me is that I prevailed upon Paul to do a cover of the Sisters of Mercy’s “Dominion” with me, which he wasn’t real happy about doing cause that’s not the kind of music he’s into. I had to get more involved with the recording of the actual tracks on that song than I usually do, but I think it turned out to be the best song on the album, from my point of view. I’m really happy about that. We performed it live for the first time in San Francisco at the DNA Lounge, which was the last night of the Death Guild Anniversary Festival that goes for 4 nights.

I am more enthused about some of the stuff we are doing now, like that show for example, than I was the entire time we were on Warner Brothers doing the band full time when a lot of what we were doing was difficult for me to believe in. When there’s a lot of money riding on the albums you are making, there’s a whole lot of people who’ve got their financial interests staked in, so you can’t do this and you can’t do that and you have to do this and you have to do that. All of that blunts your edge and dilutes your style, message, and you end up creating commercial products that are respectable but not nearly as personally gratifying as some of what we are doing now. That’s the current era, I’ve now toured you through all 5 eras of Information Society history.

- Hakatak

- Hakatak

CrypticRock.com – It sounds like a very interesting ride that you have gone through leading you to today. It has been a long journey. As you have mentioned, the climate and music changed in the ’90s and it has changed even further in the 2000’s; the way we receive music is completely different than when we once did, the way we purchase our music. What is your opinion on the current state of everything being digital now?

Kurt Harland Lason – That’s a very broad question because I’m rather garrulous. You might want to narrow it down a little for me.

CrypticRock.com – Do you feel as if the idea of purchasing music digitally has really hampered the music industry? Is that something that you think is accurate?

Kurt Harland Larson – No, of course not. No one cares whether I buy my music on a wax cylinder, a piece of aluminum, a piece of vinyl, a cassette tape, or a CD. Physical formats have changed over and over again. The big event was when people stopped buying it and were able simply to get it for free, and that’s the world we live in now. Most music now is not purchased at all, it’s simply acquired. We are in the middle of another revolution. Because of that, we are getting away from the notion of people even having the music themselves at all. I think the majority of people are going to move onto something like the Spotify model. They don’t need to have their own music collection, they just use Spotify’s music collection. I think that is a terrible thing because right now, if someone mostly uses Spotify, well I can still give him a recording in some format or another, you can still play it, and he still knows how to play it, right?

But if that model of music use prevails and enough time goes by, the technologies for being able to obtain and play music yourself will atrophy, fall away, and we’ll get back into a situation where there is this huge barrier to entry. You can’t listen to anything unless the service you use carries it. I don’t like that so much, but that’s more of the future. I think what you are referring to probably is the complete thrashing of the whole music industry as a financial entity that came about because of electronic distribution, right?

CrypticRock.com – Exactly, agreed 100% in regards to your take on Spotify. It is a terrible thing for a variety of reasons. The ones which you just outlined, but also because of the minimum amount that they pay the artist for streaming the songs.

Kurt Harland Larson – Yes, that’s a whole separate discussion, it is also very interesting. I get a lot of perspective and information about that cause of course I get the reports about that for my own songs. The bottom line on my take of that is for the artist, you compare that to the classic model that we had 30 years ago, it’s kind of six of one half dozen of the other for most artists. The details of that would take me way too long to talk about. What I will talk about is the fact that 25 years ago, you had what we call the major record labels selling pieces of plastic for a profit and enjoying a relatively healthy business. Now you mostly don’t, most of the people who had careers lost their careers in the ’90s and the 2000s as a result of vastly plummeting sales because people were able to get their music for free. While there is a lot to say about that, the first thing I always want to say is that the major record labels deserved everything that happened to them.

Here’s an anecdote that will give you an example of why I say that. In ’90 or ’91, I was in LA, as we were fairly often, I was at Warner Brothers, as we were fairly often. Back then it was pretty common for a band to go visit with their A&R guy, the artist and repertoire representative, at the label; the person to whom your band’s career within that label was assigned. I had been talking to him for some time about this thing that I had been doing for awhile that was called the internet, modems, and using BBS’s. I had been doing that since ’87, and our producer for our albums, Fred Maher, was also about our age, who was also very technically enthused and knowledgeable just as we were.

We had gotten to the point that we were just about ready to start transferring files of stuff we were working on over the phone lines using our computers, and it really made me think. It was the first time I was able to get a music file on to my computer, over the phone lines, via one kind of phone connection or another, be it direct or internet, and then up on someone else’s computer on the other end so they can then play it. I began to realize the future is here, music had been digital since the early ’80s; the CD was a digital format. I believe it was originally meant to be called DCD, which was digital compact disc, opposed to those big 12″ ones that the movies were on, laser discs. The CD was called a compact disc because it was only 5″, but the laser discs were 12″ or something, that size was chosen to be the same size as vinyl albums so that people would feel comfortable with it. I realized that now that all of the pieces are in place to start throwing this data around, there simply were no barriers to people exchanging their music. Everyone was familiar with the concept already from making tapes. You remember the whole home taping is killing music thing, right?

CrypticRock.com – Yes, making a mix tape, everyone did that.

Kurt Harland Larson – The music business was already starting to fall apart when someone in their 30’s in 1991 was a teenager. You came of age right at the beginning of the digital internet, MP3 era. The first wave of that happened in the early ’80s when home taping equipment became cheap and ubiquitous and everyone was walking around with Walkmans. I remembered at that time, the band Bow Wow Wow was touring, and we saw them in Minneapolis. They had this huge banner up behind them on the stage, and all it said was “Home taping is killing music.” That was like at the beginning of what we now think of as ’80s music; one of the more fruitful eras of Pop music ever. The digital thing was like the 2nd wave of that. I had been using the internet, I had been dialing direct to BBS’s. I even started a Prodigy account; an online service started by Sears. I had used CompuServe and all that. The point was that I had become fully aware, although it wasn’t all that common yet, that pretty soon it would be extremely common for people to trade music files back and forth with each other.

I was at Warner Brothers that day and I was talking to my A&R guy about all this stuff, and he was listening. He said, “I want Mo to hear about all this stuff, let’s go talk to him.” We just wandered over to his office. As pure luck would have it, Mo Ostin, who was one of the heads of Warner Brothers at the time, was up in his office by himself and willing to let us just walk in and talk to him. I started telling him all the stuff I started telling you. This was without any idea of exactly how it was going to play out. I said, “Look, people have these things called modems. Anything that you can get onto the computer you can transfer over the modem. I think the time is right. You can start selling music directly over to people on the computers electronically. You don’t have to print them onto plastic discs anymore, you don’t have to ship anything, people can get their music right away, they don’t have to go to the store. You should start looking into this. You need to develop your own server, it would be a hub and spoke system where everyone would call into Warner Brothers’ music server.” Everything went to the internet instead. I had a model of it in my mind, it was not all that different that what actually ended up happening. I told him all about it, he said, “Oh, that’s interesting,” and didn’t give much of a response.

We were there at the end of our LA trip too, again, and he asked our A&R guy, Kevin Laffey, to bring me in again to talk to him. This time, he was ready to really pay attention. He had a guy with him that he had brought in, I’m not sure but it seemed to me like after we talked to him the first time, he had gone and spoken to someone else at the company about this and wanted to have me back in and tell them all this crap again. It’s not like I was telling them anything that they couldn’t have already known, I think it was the first time that Mo Ostin anyway ever had anyone talk about it in a way that made it sound like maybe he should pay attention. Now, to be fair, Ostin was at the pinnacle, and towards the end of his career, by that point, he was possibly in his sixties and not that far from retirement. He guided the company in 2 periods where other things were the issues, he was used to that kind of an issue. He brought in another guy who was older than me, but probably mid to late thirties, where as I was in my late twenties, and I ran through my spiel again. The other guy was super suspicious, dismissive, and hostile to everything I was saying. Like his job was to swat away any notion that any of this could be true. I didn’t understand what was happening. Why would he act like that?

CrypticRock.com – That is a good question. One can assume they saw the writing on the wall of the future and feared it.

Kurt Harland Larson – The thesis I was presenting was that, here is a business opportunity for you, you can beat the other labels to market with an electronic distribution system which would be profitable for your company. What’s so hard about that? There are a few problems to figure out, at the time I didn’t know how fast connections could get, so sending a whole song was pretty slow. There were issues about copying that we didn’t know; if you sell an electronic file to someone then what is to prevent them from sending copies to all their friends. We didn’t really know what to think about that. There were no really good compression algorithms available at the time. The Motion Picture Group (MPG) was working on the problem. I think by that time they were already working on the Motion Picture Group Audio Layer 3 format, which became the MP, for motion picture, 3 for layer 3. The MP3 compression format was already in the works, and published in 1994.

The other guy, while Ostin mostly just listened, just kept wanting to deny everything I was saying. I didn’t really know what to do about it. I didn’t understand what would be his motivation to talk that way. The thing I very specifically remember him saying was in a really sarcastic and dismissive voice, “do you know how long it would take to send a whole song over the phone?” This is where my brain did not serve me well; I have a pretty weird way of thinking and intellectualizing about things. Most people would have responded to the point he was making. The right answer would have been: “it might take a long time now, but it might not take very long a few years from now.” But I took his question literally; in my head I went over all these calculations. I started trying to figure out how long it would actually take, to answer his literal question instead of responding to his point, which is it won’t happen cause it will take too long. The answer is yes, it will, cause it won’t take that long forever.

CrypticRock.com – Great point to make. Look where we are today with transfer of music via the internet.

Kurt Harland Larson – Do you know how long it takes to send a whole song over the internet now? Less than one second. I didn’t know about MP3, but I did say that something will probably have to be done with data compression. I didn’t know that the internet was going to become the dominant method that which people connected with each other, but I knew the internet existed. I didn’t know how fast digital connections would become, but I knew that they were getting faster and faster.

My first model was a 300 baud modem, the next one was 1200, and the third one could, under a weird mode if you had it with another person with the same brand on their end get up to 38,400 per second. I could see where the curve was going, they just ignored the whole thing; “Oh yeah well, thanks for bringing this to our attention.”

CrypticRock.com – Wow, how nearsighted and naive of them.

Kurt Harland Larson – That was part of the general response by the record industry at the time, to swat the whole thing down, to rather maintain the status quo, instead of seeing an opportunity to meet consumer demands. Interesting thing too few people understand ever, then or now: people care mostly about convenience. They only care about quality when there are no easily attainable convenience gains to be had, and as soon as there are new convenience gains to be had, they will stop caring about quality again. For example, if you listen to a song in smallish headphones on a portable player as you go out jogging, you are hearing this music with traffic noise, wind, people yelling, the sound of your own feet, and blah, blah; this ridiculous experience of trying to listen to the song with all this noise blended in, right? That’s a lower quality musical experience. But think how much more people care about the fact that they can take the music with them while they are jogging. You listen to music in the car. You got the engine noise, noise of the tires on the road, the speakers in the car aren’t that big, they don’t necessarily sound that good, and all the traffic noise, but, you can listen to your music in your car. People want convenience, they want capability, they want options. Quality is a distant fourth, and no one wanted to look at that.

CrypticRock.com – You are absolutely right. Quality is a distant fourth in consumer’s priority when it comes to convenience.

Kurt Harland Larson – The record companies were flush off their victory over the digital audio tape machine that had come out of Japan. Now, this they recognized as a huge threat because you could simply plug the digital output of a CD player into the digital input of a DAT machine. You could make a perfect, exact digital copy of a CD onto a digital audio tape. They thought, “Oh my God, this is going to destroy the record industry. We’ve got to mobilize against this.” So they made it illegal. They managed to make it impossible to sell DAT machines in this country. They set up this ridiculous copy protection scheme that just made it not worth even doing. They all refused to print commercial albums on digital audio tape and they successfully relegated the DAT machine to be a professional tool only. It had a good run, we depended on DAT tapes for 10 years as a primary professional tool of audio exchange. We even toured with DAT tapes to play certain audio clips and stuff during the show. As far a consumer item, they killed it, and they were proud of that.

Here’s where they really steered the Titanic into the iceberg. They thought that the personal computer was just another version of the digital audio tape machine. They thought that they could kill the personal computer, and I know they thought that. I was in the room with people who worked at major labels saying that they were going to kill the personal computer. They somehow could not fathom that the personal computer was a whole different phenomenon and they were not going to be able to suppress it. When they realized that they couldn’t then they thought that they could suppress audio on the personal computer. Well, no way, no you can’t, absolutely not. Then they thought that they could suppress the sharing of digital audio files. No, they couldn’t. The way they tried to go about that, their brilliant idea was to sue their customers. I am not personally aware of any other time in history when any industry sued their own customers, it boggles the mind, doesn’t it? They tried to instill fear into the hearts of the American music buying public by making a few high profile cases of suing people who had acquired music over the internet or BBS (Bulletin Board System) music sharing sites.

CrypticRock.com – It is not very endearing to do something like that to your customers.

Kurt Harland Larson – It’s like if you are a pizza restaurant, people come in and they don’t want the pizza anymore they just want some olives and some pepperoni so they somehow find a way to pull olives and pepperoni out of your food bins and they want to pay you for it. They want you to sell them olives and pepperoni, but you say, “No we make pizzas, my grandfather made pizzas in 1901 and I’ll be damned if I’m going to sell olives and pepperoni separately.” We all know what happened next right? Right next door, a big place opens up that sells olives and pepperoni, and that was Napster, which they were able to shut down cause it was basically illegal. Napster worked the bugs out of the system for people to do it legitimately, and now music is sold through iTunes, Amazon, and a handful of those other things like that. Record stores are largely gone, but not completely. How many record stores can you physically picture in your mind that are open today? I can think of 2, they are both Indies, not chains. I don’t know of any record chains other than Virgin that are really in existence, do you?

CrypticRock.com – No, is Virgin still in business? They have closed all their physical stores. The only record stores out there now are a few independent smaller ones. Then there is Amoeba which is a phenomenal California based record store.

Kurt Harland Larson – Yeah, it only takes 2 stores to make a chain. There’s an Amoeba less than a quarter mile from where I’m sitting right now in my neighborhood. There’s another local one called Rasputin Music that is just down at the end of the block here. Those are the only 2 I can think of. All that change is inevitable because people wanted the convenience of being able to browse, pick, and instantly download. They would have been willing to pay for it, they really would have. People were already shoplifting records, kids were already shoplifting records from record stores because they couldn’t afford the records. The public went to the record store and they bought the record because most adults at the time would rather have paid $7 than find some way to bug their neighbor to record that latest album for them onto a tape. The same was true, let’s say eight years ago, most people would rather pay a $1 to instantly download the song from an easy to access source that already has your credit card information with whom you feel fairly safe from viruses or other kinds of malicious activities. They would rather do that than figure out how to go to the Pirate Bay or whatever and bug their coworkers about songs that they share, they would have paid for it.

Now, in 2016, I think we have entered into a whole other, even newer realm in which, as we discussed earlier, we are seeing the beginnings of what I call post ownership era of music consumption. Almost back to the old days in which you pretty much depended on the radio for your music instead of owning your own records. People, unless they are very specific about listening to the same exact song they want to hear, and many people aren’t, it’s easier for them to just have a Spotify account, or Pandora. There will always be people like me who are control freaks about their music library, but I suspected the majority of people will be perfectly happy with services like Spotify and Pandora. Again, that’s another blow to selling recordings of your music. It’s almost impossible to make money off doing that.

The final thing I’ll point out, cause I think this is really interesting , the physical factor these days which generally gets phrased as followed, “You know CD’s are still 50% of all record sales.” People, when they say that, are usually making a point that CD’s are still popular, people like CD’s and want to own the physical object, but I have a different interpretation. CD’s are still 50% of all music sales where money actually changed hands, I don’t think it’s 50% of all music acquisitions. I think that most people are getting their music for free in one way or another by downloading it without having to pay for it, because we have something called YouTube. Downloading off YouTube is as easy as typing the words Download and YouTube into a Google Search and hitting the enter key. You will immediately be presented with more options of how to download songs off YouTube than you would ever even need. It’s like three clicks away from the YouTube page itself. I have a little thing installed right into my Chrome browser, if I’m at YouTube I just go click, click, click and I have it. Any music put on YouTube is almost instantly downloadable.

CrypticRock.com – That is completely accurate. It is really that easy.

Kurt Harland Larson – There are no barriers of any significance to downloading anything that’s on YouTube, and while other sites that have music aren’t quite that easy. Really, if you can stream it, you can download it, and once one person figures out how to download the streaming site, all that person has to do is publish a script that is publicly available, anyone can access. Everyone who cares enough to download the file themselves is getting it for free, the only reason CD’s are half of all record sales is because you can’t download a CD, you have to physically get it. I think the percentage of music acquisition that are still CDs is probably less than 5%. If you add Spotify, Pandora, and some of those services, the number would shrink to 1%. Whether or not one should add those is a bit of a debate.

CrypticRock.com – Those are all interesting points. You may have changed many readers perspective on a few things from what you presented. You elaborated pretty well on the progress of digital music. I have one last question and it is pertaining to film. CrypticRock covers music as well as film. With that said, what are some of your favorite Science Fiction or Horror movies?

Kurt Harland Larson – That’s very interesting. I have two very different answers to those two genres. I am very much not a fan of Horror movies at all. Not because I think there’s anything wrong with the genre, not because I think there aren’t enough good, well-made films in the genre, cause obviously there are. They are too effective on me, they horrify me. Other people watch a Horror film and somehow they are able to sort of hold it at arm’s length and look at it, like examine this plate or something in your hand and go, “Oh look at the craftsmanship, this is such a beautiful plate.” Well, for me, it’s right up in my face and making me feel bad, it just enters my body. I go, “No, she’s been torn apart by a wild beast.” It’s a horrible experience for me and I don’t do it, you know? It’s not the fault of the films, it’s just me, I can’t take them. I think probably the best Horror film I’ve ever seen, and obviously I haven’t seen very many, was Alien, the first one. While a lot of people would classify that as a Sci-Fi film because it’s in space, any student of the genre and the format can see that it’s made as a Horror film, wouldn’t you agree?

CrypticRock.com – Absolutely, it is a Horror film. There are other films which other people do not consider Horror films that I consider Horror films. The Shining is a Horror film. A lot of people say that is not a Horror film. Some people would call it a Thriller or Suspense, but it definitely is a Horror film.

Kurt Harland Larson – I don’t know how anyone could call a swimming pool full of blood falling out of an elevator onto a five year old not a Horror film. That’s my take on Horror films. If you are into them, more power to you. I probably can’t go there with you cause I’m too squeamish. Sci-Fi films, I am way into, I love them. As you probably know, I am a huge Star Trek fan. I am not as big a Star Wars fan as many people I know are, but nonetheless, it played a pretty big role in my life. It’s a broad genre of course. It’s a little difficult to say that Sci-Fi is a film genre because I think Adventure is a film genre and Horror is a film genre. So, for example, if you take the first Star Wars film and Alien, trying to lump them together as both Sci-Fi, is pretty awkward, isn’t it?

CrypticRock.com – It is a very broad range for sure.

Kurt Harland Larson – Right, so I don’t have as developed an opinion for the concept of a genre of film that you could call Sci-Fi, but there are plenty of films that are considered Sci-Fi that I love. Among my favorites are almost all of the Star Trek movies. I’m pretty open to all of the Star Wars movies. Some people even call Mad Max Sci-Fi, and I love those, the one from last year was flawless almost. Of course Blade Runner (1982) is one of my top 12 films. The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) was a hugely influential favorite of mine, I saw it when it was new in the theater in the 70’s and it defined my aspirations of my own personal aesthetic for many years. You notice how Thomas Jerome Newton really sort of, years before the fact came, already looked like the archetypical New Wave, well-dressed young man in a suit. The Terminator films, I really liked when they first came out. Later, I looked back at them and they are not as awesome as I thought they were when I was 21, but so what. They were awesome when I was 21 and that matters.

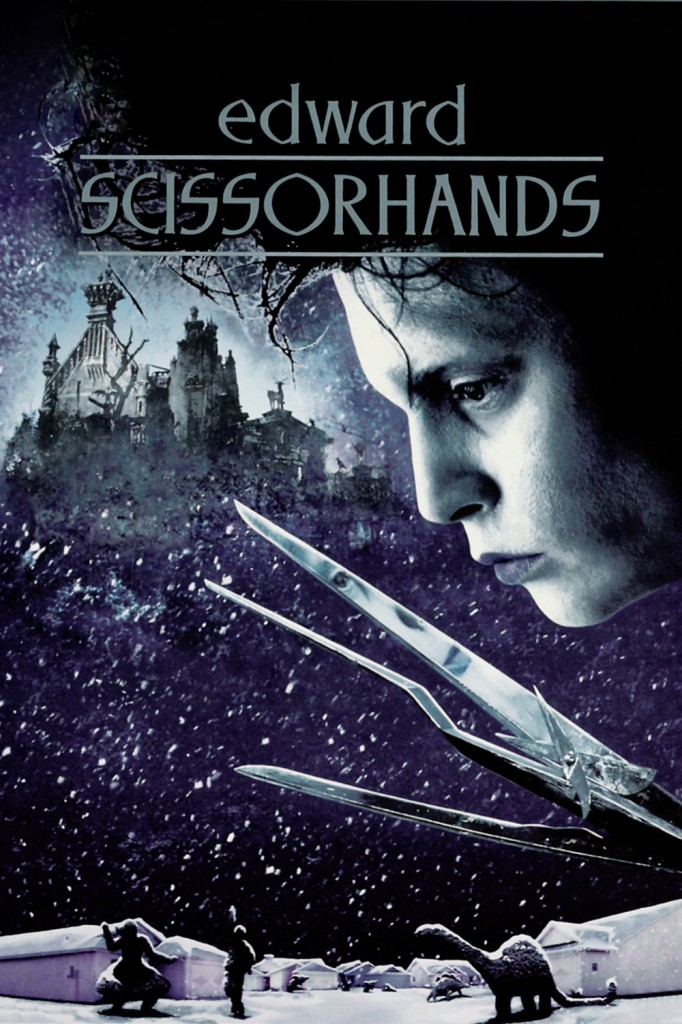

Sci-Fi films are usually… not many of them are in my top 12 list. In order, because people ask me so I have it written down, they are The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), Wings of Desire (1987), Director’s Cut of Blade Runner, The Man Who Fell to Earth, Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), The Elephant Man (1980), Dead Man (1995), Edward Scissorhands (1990), Being There (1979), The Terminator (1984), and Eraserhead (1977). Only a few of those could remotely be called Sci-Fi, although I am tempted to add Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) into that list.

CrypticRock.com – That is a very diverse list of movies. Do you have some favorite directors?

Kurt Harland Larson – Some of my favorite directors are Wes Anderson, Werner Herzog, Tim Burton, Sofia Coppola. Most of what I like in films is not very popular, I have to see very small and independent films to get this. I like films that aren’t rushed, that aren’t hysterically over-dramatic. I like films like the most recent Cohen Brothers film, 2016’s Hail, Ceasar!, which is excellent. I like films that are willing to show you something just to entertain you even if it doesn’t advance the plot; things that more evoke states of being rather than do nothing but tell a narrative.

I think that’s why Blade Runner was so successful in a cult way and difficult to market. Much of what it accomplished was independent of its actual narrative. It depicted a dystopian future in a stunningly, compellingly, and resonantly visual manner that simply hadn’t been done before. I think that film had impacted people visually more than it did narratively. As you know, the story was just sort of a 1949 gumshoe story. The world evoked was groundbreaking. I tend to like movies more for their mood and for their atmosphere than for their story. In fact, I think our whole culture is terribly over-narratized at this point; narrative is just hugely overdone and overblown in our culture right now and I find it tiring.

- Warner Bros

- 20th Century Fox

CrypticRock.com – Everyone likes different things. Some people enjoy dialog, some people enjoy an atmosphere, as you have said. I think atmosphere is very important for a film.

Kurt Harland Larson – An example of what I mean by over-narratized is, for example, in video games where I’ve worked for the last 20 years, it’s gone up and down over the years, but on average, there’s always been way too much effort into the telling stories when making video games. I think the people making the video games, many of them would really rather be making movies.

CrypticRock.com – Right, and a lot of times you see a lot of these video games, they do eventually make into movies at some point.

Kurt Harland Larson – And vice versa. Usually it’s the other way around, of course that’s how it started. It was done often and duly noted in the games industry when they started making movies out of games. The feeling was “ha ha, now the film industry can bow to us”. Well the film industry was already bowing to the game industry when they realized that we were making 10 times as much money as them. Most of the LA film industry people approached the games industry with an extremely arrogant “we will show you how it’s done kid” attitude which worked cause the games industry was mostly young people who idolized film.

Tour Dates:

2-11-2017 The 80s Cruise Ocho Rios, Jamaica

For more on Information Society: informationsociety.us | Facebook | Twitter

Purchase Orders of Magnitude: Amazon | iTunes