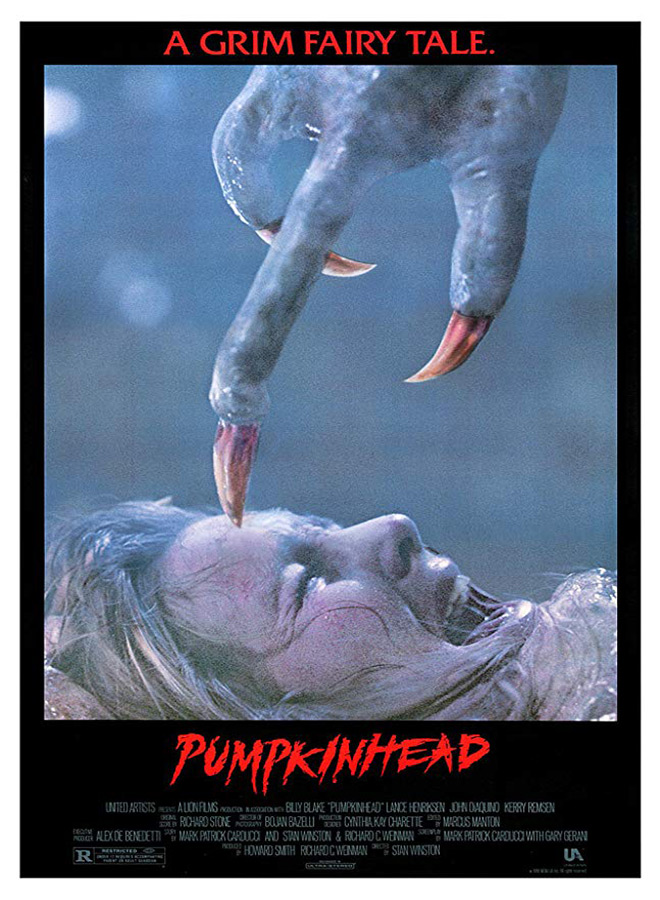

There is a dormant hatred that exists within a parent. It is like a half-screwed lightbulb in a boarded-up attic within their consciousness. The lightbulb is not meant to ever be twisted in soundly because there’s nothing of import to shine light on. In most cases, it remains unilluminated forever. The parent’s child grows over the years into self-sufficiency, eventually moves on to have a child of their own, and thus, the dust in the attic is left undisturbed. When, however, that beloved child is hurt or killed at the hands of another, the dust quivers and that old lightbulb that remained cold for so long, suddenly shines with an unfathomable wattage of malice that bring its bearer to the very rim of hell and its receiver. Such is the story of 1988’s sleeper, cult classic Horror film, Pumpkinhead.

Near universally panned by critics in its time, Pumpkinhead‘s popularity upon its limited USA release on October 14, 1988 was retarded by its lack of novelty; critics rightfully had blinders on. They had seen almost two decades of creatures and creeps hacking teens up. No matter how creative the kills were by themselves, the conceit of it was stale. As time chugged forward and VCRs found their way into even lower-income homes, people grew tired of watching and re-watching Freddy Krueger traipse through dreamscapes and Jason Voorhees traipse through…everywhere. Horror fans raided their video stores and sought out the particles that slipped past them in theaters and Pumpkinhead earned its due but hesitantly-given respect. Its old-world, simple appeal and whimsical execution by Effectsmaker and Director Stan Winston reminded audiences that there could still be magic and poetry in a genre that had become primarily known for splatter and gratuity.

Based on an actual poem by enigmatic Writer Ed Justin, Pumpkinhead is the sleepy, old story of Ed Harley, played by the venerable Lance Henriksen (Near Dark 1987, Hard Target 1993), a shopkeeper in a rural backwater somewhere within the Dust Bowl; jagged and crooked-toothed dentures were made for Henriksen to give him a more backwoods tarnish. Harley has very little to call his own, but he has a son and in those idyllic opening minutes of the film, it is made clear that as long as he has his son, the rest of the world could be on fire and he wouldn’t bat an eye.

Since the advent of film, young children have been a sort of sacred cow. Killing them on screen is a line that only the boldest of filmmakers cross. People walk out of films for less, but the ever-intrepid Winston sprinted across that line when he shows Harley’s cherished son get run down by a posse of teenage suburbanites on motocross bikes. Harley, in his insurmountable grief, coerces local witch, Haggis (Florence Schauffler: Bachelor Party 1984, Problem Child 1990), into conjuring the eponymous Pumpkinhead, a Xenoid revenge demon who lay interred in a deepwoods pumpkin patch. Haggis does the ceremony under protest and is not alone in voicing her concern about him diving into this diabolical molasses.

Now these city slickers each land somewhere on the spectrum of good and evil and, traditionally, the most benevolent characters of a Horror movie are among the last killed; more often than not, they become the sole survivors. Winston shatters this convention as well when Pumpkinhead kills off the only characters with a modicum of compassion first. Pumpkinhead is relentless and indiscriminate, and the more it kills, the stronger Harley’s buyer’s remorse grows. Dictated in the arcane caveats of this dark hick-magic, he and the creature begin to reflect each other physically and mentally. By virtue of necessity, he becomes an ally to his son’s dispatchers and joins the fight against Pumpkinhead. In the end, Harley turns the gun on himself to stop the carnage. With the source of the curse gone, Pumpkinhead bursts into flames and the witch Haggis buries Harley’s body in the pumpkin patch so that someday, the cycle can continue.

For the majority of the film, Harley is embittered and remorseful so the audience reluctantly roots for him, but also acknowledges that, in a sense, he dug this hole for himself; even Haggis the witch calls him a fool. There is no one in the film to truly attach to and cheer on, but in a tale like this, the characters take a backseat to a sort of storytelling that transcends borders and times.

The film, though not wildly popular, was considered a success by studio standards in that it not only recouped its studio costs, but turned a profit as well. On its release weekend, it was handily overshadowed by the Jodie Foster vehicle, The Accused (1988), but at the end of its run, it managed to gross roughly $4.4 million domestically for its studio, De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, which put it just shy of a $1 million more than its budget of $3.5 million. Also released that weekend was a little film called Night Of The Demons, which fared much worse than Pumpkinhead in the box office, but went on to enjoy a similar level of cult classichood. The creature itself—sometimes a man in a suit and sometimes a puppet—was created by its Director Stan Winston, who was an enormously prolific luminary of the special effects world. When a practically-created creature can withstand lingering close-up shots, it is a testament to the skill of the effects artist and Winston was the best in the business.

If Pumpkinhead were remade with the sensibilities of today’s top and rising film writers, the development of the disposable characters would be more thorough and would likely drive the film. The literal demon would be boiled down to a figurehead that forced an aloof twenty-something to confront a personal demon in the midst of bloody pandemonium. It would focus too much on the characters and not enough on the subtle, folksy Americana of “telling the tale.” Perhaps it would give Pumpkinhead’s origin story and tear away the illusory potential for Pumpkinhead to be under your bed. Pumpkinhead, for all of its faults, remained in the realm of the campfire story. Sure, it kowtowed to the studio demands for teenage victims, but when those layers of dead skin are peeled away, the muscles and skeleton of the film concern a man who summoned a demon for revenge and got more than he bargained for. That’s a tale that could just as easily have come out of the mouth of Aesop or Uncle Remus.

Pumpkinhead is neo-folklore. Ed Justin’s poem is slumber party fare meant to scare excitable children. It harkens back to a time before video when silhouettes on a wall and words whispered in the dark were the main forces that drove the youth under the covers—when the bogeymen were formed not on the screen, but on the limitless format of young imagination. Pumpkinhead warns us that fires set by hatred are wild and uncontrollable. When stoking the embers of revenge, everyone gets burned.

wonderful film, one of the best horror movies from its decade. It stands up remarkably well and continues to charm with its ec comic flavored rich atmoshere. Lance is also a powerful engine driving this wheel. One of his most memorable roles

I absolutely love this film