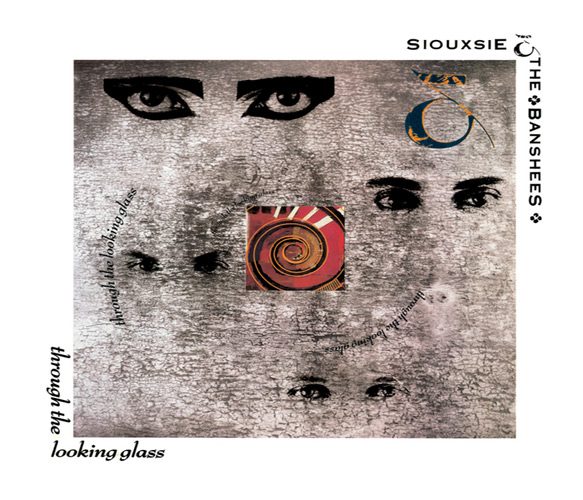

By the time they released Through the Looking Glass, Siouxsie & the Banshees had already a well-developed and unmistakably distinct sound and image. After all, at the time, they were on their eleventh year of activity; and the album was their eighth – which showed how prolific Siouxsie & the Banshees were, especially during the first half of their primary existence, from 1976 to 1996 – a full two decades. This is the primary reason Siouxsie & the Banshees’ eighth album sounded very cohesive and stylistically original, even 30 years later.

By the time they released Through the Looking Glass, Siouxsie & the Banshees had already a well-developed and unmistakably distinct sound and image. After all, at the time, they were on their eleventh year of activity; and the album was their eighth – which showed how prolific Siouxsie & the Banshees were, especially during the first half of their primary existence, from 1976 to 1996 – a full two decades. This is the primary reason Siouxsie & the Banshees’ eighth album sounded very cohesive and stylistically original, even 30 years later.

While Through the Looking Glass consisted entirely of other artists’ songs, the quartet of Siouxsie Sioux (vocals), Steve Severin (bass/keyboards), John Valentine Carruthers (guitars/keyboards), and Budgie (drums/percussion) restructured them to fit their sonic trademark of Tribal and percussive drum beats; ominous-sounding, tubular basslines; Middle Eastern–influenced, flanger-and-reverb-heavy guitar strums and plucks; Bach-inspired keyboard melodies full of toccatas and fugues; and, of course, Sioux’s quirky, chirpy, partly operatic and partly carnivalesque singing voice and ghostly wails that were both soothing and unsettling at the same time.

Released on March 2, 1987, Through the Looking Glass was practically the full blossoming of a seed of concept that Siouxsie & the Banshees had sown as early as 1983, when they released their first-ever cover song – a Gothic New Wave treatment of “Dear Prudence,” which emerged off the studio totally unrecognizable, yet aurally beautiful. The band members’ ability to deconstruct a song and then transform it into something distinctive with their own style worked well in that Psychedelic Folk Rock classic by no less than The Beatles, enough to catapult Siouxsie & the Banshees’ version onto the Top 3 spot of that year’s U.K. Singles Chart, inspiring the creatively driven group to pursue developing a full album of the same treatment, resulting in the aforementioned and hereby-described masterwork.

Through the Looking Glass opens with the similarly slashing and spiraling, yet heavily textured rendition of Sparks’ “This Town Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us,” with which the theatrical and operatic becomes Gothic and Tribal. What follows next shows how Siouxsie & the Banshees have breathed human life into the otherwise robotic, monotonal, and metronomic “Hall of Mirrors,” yet retaining the mystical and hypnotic elements of the Kraftwerk original. The dizzying melodies flow into the ensuing “Trust in Me,” whose cascading piano flourishes make it leap effectively from the animated eeriness of the Jungle Book ditty to the more calculated and cunning allure of the new one.

One of the highlights of the album, the Folk Rock simplicity of “The Wheel’s on Fire” gets transformed into the charging and engaging Post-Punk sensibilities of Siouxsie & the Banshees’ version; more so, Dylan’s draggy and deadpan drawls get adrenalized to become Siouxsie’s mellifluous wails and chants. “Strange Fruit” is an altogether different affair, in which Siouxsie & the Banshees had seemingly ritualized the sensually morbid Billie Holiday classic to make it a proper orchestral downtempo dirge.

The mood changes as the following track, “You’re Lost Little Girl,” plays next – a Psychedelic Rock classic by The Doors that becomes a theatrical Gothic piece, infused with a Cirque-inspired interlude that will remind the initiated of similar circus-gypsy excursions in The Beatles’ “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite,” David Bowie’s “Little Bombardier,” and Paul & Linda McCartney’s “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey.”

A sense of respect for Iggy Pop’s already engaging “The Passenger” was apparent, as Sioux and the rest had obviously maintained its tempo, beats, and grooves and simply upped the ante by incorporating bells and brass accompaniment, which worked well to the song’s advantage, making it another standout track off Through the Looking Glass and whose instrumentation served as a foundation to the ensuing year’s follow-up, 1988’s Peepshow, as epitomized by the chart-topping “Peek-a-Boo” and “The Killing Jar.”

Then there is “Gun,” with the double-time rhythm and proto-Grunge guitar aesthetics of the John Cale song’s having been slightly restructured and subsequently coming across as an angular, caricaturesque, and dancey Punkabilly-dashed stomper akin to the likes of The Cure’s “The Love Cats,” The Polecats’ “Make a Circuit with Me,” and The Screaming Blue Messiahs’ “55 the Law.”

The penultimate track was Siouxsie & the Banshees’ successful attempt to shorten and Gothify the seven-minute Glam Pop indulgence of Bryan Ferry and the rest of Roxy Music in their song “Sea Breezes.” Finally, the ever-daring group wrapped up their eighth opus with a Psychedelic-tinged rendition of Television’s “Little Johnny Jewel,” which completed the stylistic circle and took the sonic seeds back to their roots, for the treatment was not dissimilar with what Sioux, Severin, Budgie, and Robert Smith had done with The Beatles’ classic five years before Through the Looking Glass.

In retrospect, Through the Looking Glass is an obvious standout in Siouxsie & the Banshees’ discography for its being the only full-length covers album that the legendary English band had ever released. However, because the band was able to convert the songs in a style that was distinctively its own, the album fit flawlessly in the band’s sonic ethos, preventing it from turning into an anomaly. In the current era of million music genres, Through the Looking Glass still remains a delicacy of the same degree of uniqueness and palatability as when it was first released, thirty years ago.

No comment