The hellish vampire had a miniature revival with the 2024 Robert Eggers film Nosferatu. This is one of many retellings of a gothic tale over two centuries old.

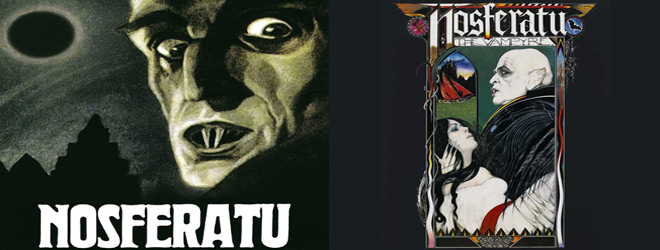

Looking back, the original Nosferatu is a German Expressionist film released in 1922 in Germany and 1929 in the United States. It was a black-and-white silent film with orchestration to accompany Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. This film was an unauthorized retelling of the Bram Stoker classic Dracula, which actually has its own history. No claim was made with the Stoker estate to create the film, and upon its release, Stoker’s Wife, Florence Balcombe, filed a legal dispute, resulting in the film losing its screening access worldwide and many copies being burned.

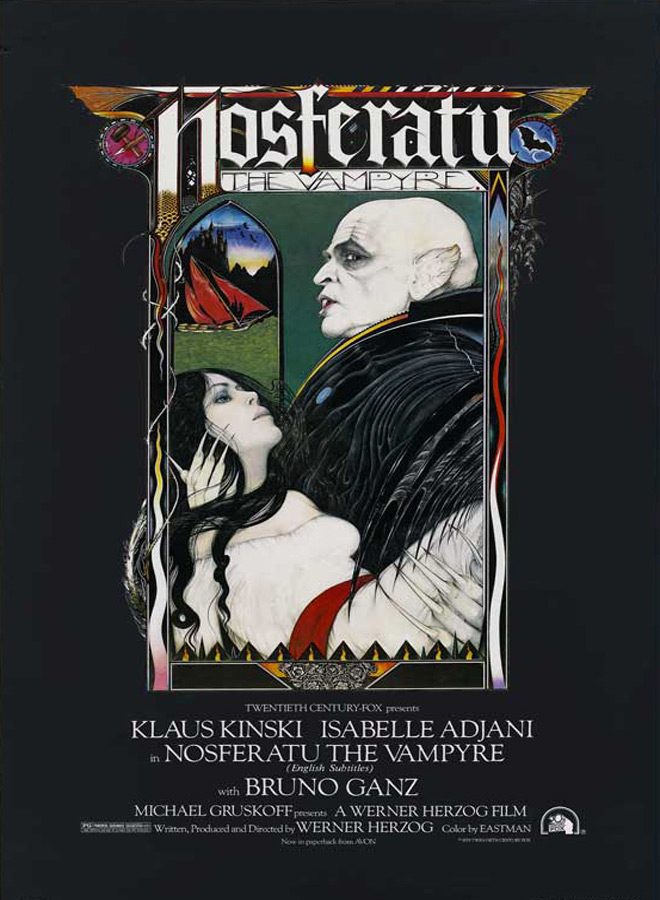

It is an act of cult film perseverance that the original film can still be watched today. For years, it was hidden away until Dracula entered the public domain in the ’60s. Two decades later, Werner Herzog took a shot at recreating the occult film. This time, the film was titled Nosferatu, Phantom der Nocht in German and Nosferatu, The Vampyre in English. This is not the only remake of this Nosferatu myth, but it is the most well-known. Other than the obvious advances in filmmaking technology, there are many quirks between the definitive 1922 version and the well-known 1979 remake.

To avoid needing authorization for their film, the original moved the setting to Wisborg, Germany, a semi-rural village. The remake followed suit and stayed in Germany but relocated to Wismar, a much more urban environment. The creators of the original also changed all the characters’ names. This is where Count Orlok rises from. The rest of the characters have much more forgettable aliases: Hutter for Harker, Ellen for Mina, Ruth for Lucy, Knock for Renfield, Seivers as Seward, and Bulwer as Van Helsing. Now, let us go on to define the winged flights and failures of each film.

1922’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror is a product of its time, a specific era in German filmmaking history. The grainy black-and-white film and novice transitions take a few minutes to get used to, but once the brain has accepted this as part of the film, the true fun can begin. This film has achieved critical acclaim for good reason; the storytelling is extremely clear despite the lack of dialogue.

The strategic use of varied title cards helps to progress the plot and the characters in a linear manner. There is no room for complex characters in the hour-and-a-half run time. This also results in a relatively quick exposition as Hutter travels abroad to meet Orlok. In contemporary viewing, some title cards feel unnecessary and obtrusive at times, but as the story progresses, they become much more helpful to the plot.

Thematically, science and magic play a large role in the 1922 film. Bulwer is stated to be a Paracelsian, a believer in the occult, and there are scenes that posit the possibilities of the advancement of many new sciences to alleviate the stress of the cultish world these characters live in. These scenes are counterparts to the actions Orlok performs when no one is watching. Particularly because this telling of the Dracula myth has much more deliberate usage of magic. Orlok is seen phasing through walls and levitating coffin doors; his power is never questioned, and he seems to be a given to the character.

The movie is most well-known for its ending sequence. After Knock has exhausted himself as the comedic relief, Orlok begins his creeping shadowy descent on Ellen, stalking her in her bed until finally, the glory of all vampire films arrives. The bite scene. This bite scene is weak compared to many other kitschy vamp flicks or even in the contest with more Horror-based films. The shot is stationary; Ellen has no autonomy as Orlok descends. It is as if he has punctured the neck of a mannequin. To jump ahead, the 1979 version’s bite scene is quite literally to die for.

The acting is decent, the pacing is done well in the original, and there is some dry humor that works very well with the actors’ overexaggerated movements. The musical score does a lot of heavy lifting to move the narrative along and create suspense. This heavy lifting is purposeful, though; the musical score of the film is beautifully composed and becomes a living part of the story as the viewer is sucked in.

In comparison to the 1922 version, it is apparent that the 1979 film takes many scenes exactly from the original. The film is both an artistic recreation and a simple remaster. This version has an extra twenty minutes of runtime, but only about half of that time is used correctly. Herzog chooses to focus on the wrong aspects of the story and ends up with a movie that is dryer than the original in some places and feels much longer than it actually is. The pacing is slow, there is a strange bat that seems to fly to nowhere for a cumulative six minutes within the film, and the river between the Carpathian village and Dracula’s castle gets more screen time than Van Helsing’s character.

There are also a few added scenes that turn the movie into an extravaganza. These are things that just could not be possible in the ’20s when the first film was made. The plague, Dracula’s scourge from the dirt of his motherland, takes a larger role in this film than in the first. The sheer volume of rats in the film is disturbing. There is some earned discomfort for any viewer who watches as a horde of over one hundred rats piles over each other, squealing and gnawing at themselves on the streets of Wismar. There is also the plague party, which is… perfect.

This is the exact level of imagination needed to separate the remake from the first film. Using stunning color, Christian imagery, a disturbing number of rats, sparse dialogue, and a grand musical score, Herzog encapsulated the entire experience of the film into a single scene that is completely novel to the film. If one were to choose which film to watch, the meat and potatoes would overflow in the remake. But so is the blandness and drawn-out scenes that seem to bring little to the viewer.

The remake of the film follows the same plotline as the first but executes the ending in two starkly innovative ways. First is the transformation of Harker into a walking corpse; the first film does not utilize the possibility of a human becoming a vampire, which is a shame because the remake turns it into a crucial plot point that specifically allows Lucy to shine as a character. The second important change in the remake is Lucy’s (Ellen in 1922) character arc. Along with the actress who plays Lucy, Isabelle Adjani, being a perfect gothic princess who outshines her counterpart in the original, her character also has much more autonomy in the penultimate scenes of the film.

It is Lucy who finds Dracula’s coffins and consecrates the ground, it is Lucy who safeguards herself against a slowly turning Harker, and it is Lucy who keeps Dracula at her side throughout the entire night until the first crow of the cock. This is a more rewarding narrative than the first film, which gives no explanation as to why Orlok stays the entire night and does not attempt to foil Orlok’s life within Wisborg. Regarding the ending, the remake is much cleaner and tied together than the first, which seems to run past the viewer at all too fast a pace with loose ends and a weak explanation of magic to turn the final pages of the story.

There is much more to say about the color grading of the remake, the attention to detail with some shots as replicas of the original, and the orchestra musical score that pipes in grand suspense and flows from scene to scene to create a beautifully put-together movie. One interesting fact about the film is that it was made twice during its production. Most of the actors were bilingual in German and English, and each scene was shot in both languages. These long gothic scenes being shot twice likely added to the haziness that seems to swarm the film as it progresses.

However, in an attempt to avoid spoiling the whole film, we will leave you with this strange superlative rating system. Watch 1922’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror with a small group of friends who love cinema and can make a healthy critique of the movie while watching it. Watch 1979’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror either if you love gothic romanticism, harrowing imagery, and late ’70s color grading or if you are at a Halloween costume party and it is not late enough for full snuff or gore yet.

Overall, both films are a knockout, but they serve different purposes. Because of the context of their creation as well as the budget and technology of their filming. That is why this is a rare instance that an original film and remake are both worth the time put into experiencing them.

No comment