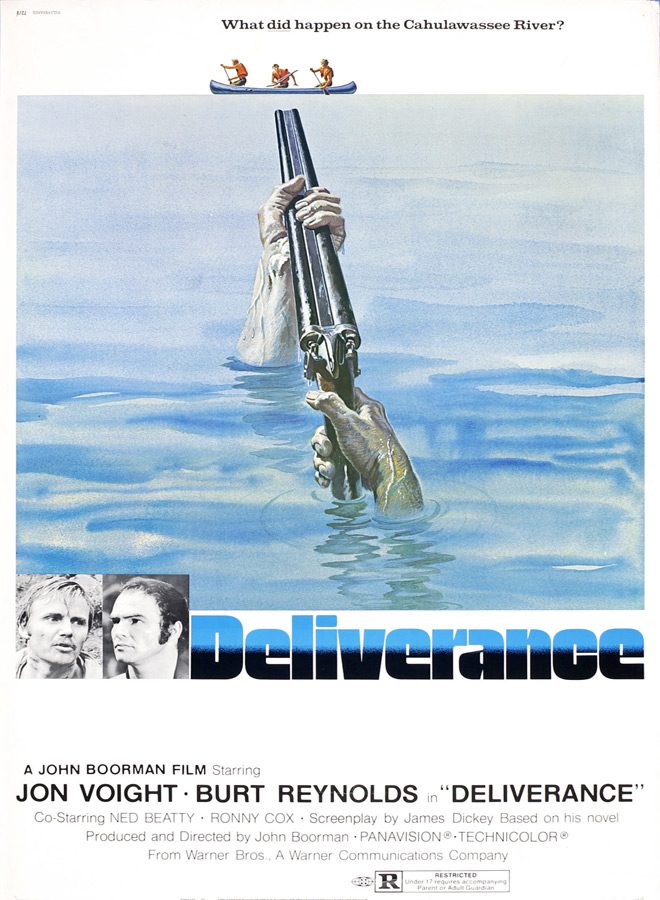

“I bet you can squeal like a pig. Weeeeeee!” These unsettling words will forever allude to one of the most momentous and notoriously disturbing scenes in cinematic history. Despite its disconcerting content, Deliverance is still considered among the top 100 films that every person should see and was nominated for 13 awards, which consisted of three Academy Awards (including Best Picture) and five Golden Globes. It also won the National Board of Review Award for Top Ten Films in 1972, was the fifth highest-grossing film that year, and even earned a spot on the National Film Registry in 2008 by the National Film Preservation Board. So, what exactly was it that made this film so pioneering 45 years ago and yet still so impactful to this very day?

Before exploring the cultural and cinematic significance of Deliverance, it must first be noted that this critically acclaimed American Adventure/Drama/Thriller was directed by English Director/Writer/Producer John Boorman (Excalibur 1981, Hope and Glory 1987) and written by James Dickey (The Call of the Wild TV movie 1976); who was also responsible for writing the book that he fallaciously claimed to be a factual account, and for which the film shares its title with and was based on. The movie premiered in New York City theaters on July 30th of 1972, via Warner Bros., in association with Elmer Enterprises; and was later released on VHS 20 years later by Warner Home Video.

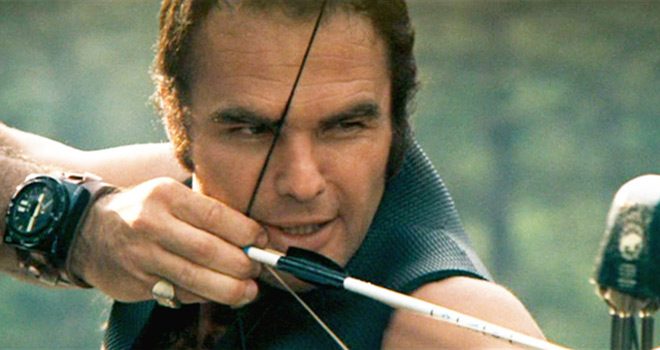

The movie included a rather masterful cast that will always be known for the quintessentially dissimilar roles they proficiently portrayed in this film. It also reignited the career of Jon Voight (Heat 1995, Mission: Impossible 1996) – who exceptionally played the role of Ed Gentry; was the first film appearance of 25-year veteran Stage Actor Ned Beatty (Toy Story 3 2010, Rango 2011) – who perfectly embodied insurance salesman Bobby Trippe; was the debut feature film performance by famed Actor/Singer-Songwriter/Musician, Ronny Cox (RoboCop 1987, Total Recall 1990) – who incredibly depicted banjo-dueling buddy Drew Ballinger; and jump-started the then baby-faced Burt Reynolds’s (The Longest Yard 1975, Boogie Nights 1997) acting career in what would be considered his breakthrough role as the macho, thrill-seeking, wilderness-adoring Lewis Medlock.

It also included performances by Billy Redden (Big Fish 2003, Outrage: Born in Terror 2009) as the young and unsettling local boy, Lonnie; Bill McKinney (First Blood 1982, The Green Mile 1999) as the rough-edged and sadistic Mountain Man; and Herbert “Cowboy” Coward (Ghost Town: The Movie 2007) as the “pretty mouth” loving hillbilly Toothless Man. Before deciding on this cast though, the roles of Ed and Lewis were initially offered to a plethora of prominent actors at that time, namely Donald Sutherland, Henry Fonda, Steve McQueen, James Stewart, Gene Hackman, Charlton Heston, and Lee Marvin; all of whom turned them down. Interestingly, Jack Nicholson was also propositioned to play Ed, but would only do so under the conditions that Marlon Brando play Lewis and he get paid $1 million; which would’ve been half of the film’s entire budget.

Aside from employing an impressive cast and crew, the film also told an auspiciously frightening story that was not only meant to elicit shock and awe but also set out to expose the taboo subculture of fanatical small-town folk that is comprised of uncivilized, lawless, ignorant, savage, brutal, inbred, backwoods hillbillies that are both suspicious of and prejudiced against any and all outsiders. With that said, Deliverance tells the formidable tale of four city boys who decide to embark on a canoe trip to uncharted territory down the Cahulawassee River in Georgia, before a dam project completely ruins the region and leaves it lost forever.

Even after receiving repeated warnings from the grimy, impoverished locals, and Drew’s (Cox) ominous and infamous “Dueling Banjos” showdown with impassive, inbred mute, Lonnie (Redden), Ed (Voight), Bobby (Beatty), and Drew hesitantly continue on with their trip that was first suggested by their outdoorsy, outspoken, and adventurous friend, Lewis (Reynolds). During their journey downriver though, they have an unexpected and unforgettably atrocious run-in with the nameless monstrous moonshiners – known only as the Mountain Man (McKinney) and the Toothless Man (Coward) – which then sets off a series of events that leave the city slickers beaten, broken, and battling Mother Nature, madmen, and themselves just to stay alive.

With so many complementary elements that effortlessly came together to produce this influential cinematic success, there was no quality more redeeming than its brilliant, breathtaking cinematography. Boorman knew just how strenuous and demanding filming would be for this movie, which is why he made the ingenious decision to bring on Vilmos Zsigmond (The Long Goodbye 1973, Close Encounters of the Third Kind 1977), the Hungarian-American Cinematographer who famously captured the 1956 Soviet Invasion of Hungary on film, amidst the threat of Russian tanks and guns.

Zsigmond’s signature use of vivid colors and natural light made the river and surrounding scenery appear far too picturesque for the film’s grim subject matter; so in an effort to diminish its overwhelming beauty, the color had to be greatly desaturated. Also, while some of the filming locations included North Carolina and South Carolina, much of the film’s visually captivating cinematography was captured along the Chattooga River in Georgia; for which 30 drownings actually occurred, in the year following the film’s release, because individuals were attempting to replicate the men’s daring adventures.

Deliverance was essentially void of any real film score, which some may take issue with, but it was not without affecting purpose. Outside of “Dueling Banjos” and brief variations of the song that sporadically played on a solo banjo which changed pace and pitch to better match the mood and intensity of the scene, music was omitted to provide viewers with a more authentic experience. To do this, Boorman ultimately relied more on the natural sounds to enhance the story’s immersive capabilities; overpoweringly rushing waters, uncontrollably chirping crickets, unbearably deafening cicadas, slightly weakened croaking frogs, and the obnoxious bird songs brought on the second the sun peeks out over the horizon.

The most valuable component of this film is the multitude of themes that are explored and exploited throughout, including survival – awakened by the conflict of Man vs. Nature; civilization – provoked by the conflict of Man vs. Man; and most importantly, ethical dilemmas – stimulated from the conflict of Man vs. Himself. The cinematic significance of Deliverance not only revolved around its powerful themes and the acknowledgement of the unpredictability and viciousness of man over nature and its creatures but also its focus on forcing men, who were otherwise unfeeling about the subject of rape at the time, to face it and suffer through it via its graphic portrayal and the bold decision to make the victim a man.

Deliverance is without a doubt a film that should be viewed by everyone at least once in their life, but it is certainly not without its faults. The dialogue, which was taken verbatim from the book, lacked depth. The pacing was inconsistent and certain moments seemed to drag on far longer than necessary. There is also very little violence outside of the film’s infamous rape scene, so gore hounds will have to find their fix somewhere else. Even some of the moments of internal struggle were exaggerated and a little unfounded, as it was difficult to believe that one would struggle so deeply with doing what was necessary to stay alive.

With all that being said, Deliverance’s minor flaws are in no way comparable to its groundbreaking substance, meaning, illustration, and influence even after 45 years.

No comment