People can name any Hollywood classic off the top of their heads. Some may even know Asian cinema through the works of Kurosawa, Wong Kar-Wai, or the Bollywood scene. But mention African cinema and the results will likely get more obscure; maybe a mention of Nollywood here, or Uganda-set Western productions like 2006’s The Last King of Scotland or 2016’s Queen of Katwe.

That is not to say there are not cinematic classics made top-to-toe by Africans. Dedicated cinephiles will be familiar with 1987’s Yeelen from Mali and 1995’s Keïta! L’Heritage du Griot from Burkina Faso. The films simply did not have Fox Searchlight or Disney handling their distribution, so they are more likely to be found in the World Cinema section of movie stores – or in sneaky YouTube uploads.

South Africa is more visible by comparison via directors like Neil Blomkamp (District 9 2009, Chappie 2015) or cult films like 1980’s The Gods Must Be Crazy. Though for most, getting into the film scene is not any easier in Johannesburg than in Bamako, Ouagadoudou or Kampala – which is where Film School Africa comes in.

Directed by Nathan Pfaff (The Advocate 2014), the documentary covers how casting director Katie Taylor (Spider-Man 3 2007, 10,000 BC 2008) left her high-end job in Hollywood to start a project in South Africa. Her goal? To help the country’s township communities empower and express themselves through the art of filmmaking.

The film originally came out on December 3, 2017, getting accolades on the festival circuit. It cropped up at the Calgary International Film Festival, the Heartland International Film Festival, and the Barcelona Film Festival, where it won the Documentary Special Jury Prize in 2018. Now everyone else will be able to see the full film on digital platforms as of January 17, 2020, thanks to Global Digital Releasing. But how well does it live up to the hype?

Well, it certainly helps that this documentary is not about one white American saving the South African townships. Instead, the film gives plenty of time to the school’s students and staff, like Gasthon Lewis and Thando Dyantyi, for their own thoughts and feelings on the school and filmmaking. If anything, Taylor simply serves to introduce the school’s different branches- Strand, Somerset West, etc.- before it shifts perspective to the branches’ students.

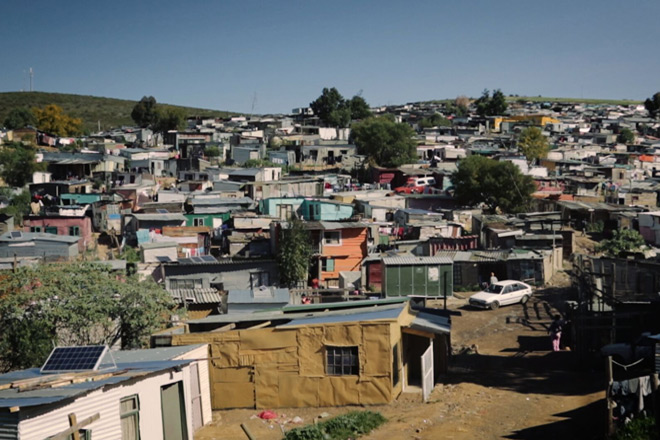

Which is likely for the best, as the film is at its strongest when they talk about themselves and their work. The Film School Africa students often bring up how they rarely get to express themselves in their communities because subjects like art and film were ‘for rich people’- people who did not have to worry about earning a living. There was a cultural barrier to creating art, along with a socio-economic and racial one. Apartheid may have ended, but the memories remain and certain communities rarely intermingle.

Film School Africa’s head of post-production Marie Midcalf (Super Cute 2018) poignantly discusses the topic, saying that as a white South African she has to accept responsibility for apartheid, township poverty, etc., because her ancestors benefited from it. The film also shows this angle through Afrikaner student Juan van der Walt. He gets on perfectly well with his classmates and enjoys his work. Yet his suburban background has conditioned him to be wary of working in the townships, so he is shown gradually overcoming this and warming up to places like Kayamundi.

The students show little to no hesitation in expressing themselves when the opportunity arises, and they end up making films that, while rough around the edges, come from personal experience. The results of street violence, suicide, and even just the drudgery of chores, make for some stark, sincere and even touching film clips that showcase some strong talent in Film School Africa’s wings. In this, the documentary demonstrates how talent is not split by social status, but chances to nurture and expand it are, and Film School Africa seems to do a good job at leveling that ground.

There are a few downsides to film, however, they are not particularly major ones. It takes time to build up steam and feel like a documentary, as it starts off feeling more like an induction video for the school’s new students. The film gets into the swing of things soon enough, though the beginning does make one wonder if they dropped their prospectus somewhere.

Also, one’s mileage may vary, but some of the subtitles are redundant. The film is nearly entirely in English, though a few of the interviewees have strong accents. However, perhaps to play it safe, anyone with a notable accent gets subtitles. It is nice to cover one’s bases. However, most of the people interviewed sound much more coherent than, say, much of the cast in 1996’s Scottish drama Trainspotting, so it does not feel like a big worry.

Overall, Film School Africa is a sweet documentary that feels honest about its intentions, communities, classes and colleagues. The film keeps a hopeful, optimistic view while not shying away from the hard facts behind social inequality in South Africa, or from what life in the townships is like. It offers a promising look into student filmmaking, and despite some early pacing issues, makes for a fascinating watch. Thus, for these reasons, Cryptic Rock gives this film 4 out of 5 stars.