Even those with the steeliest of demeanours can end up falling for the right amount of charm. It just takes knowing the right things to say and do as well as doing a convincing job of meaning it. The most successful charmers can even beat out over reason, where their marks will choose them over the hard truths. They do not even have to be knowing, Machiavellian schemers. Just someone who believes their own blather.

One of the more notorious examples of this was when Leslie Van Houten, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Susan Atkins amongst others became part of Charles Manson’s ‘family.’ They remained enraptured by him even after their arrest and imprisonment for committing murder at his behest. It was not until later, after they started speaking to a grad student called Karlene Faith, that they began to see the reality of their situation.

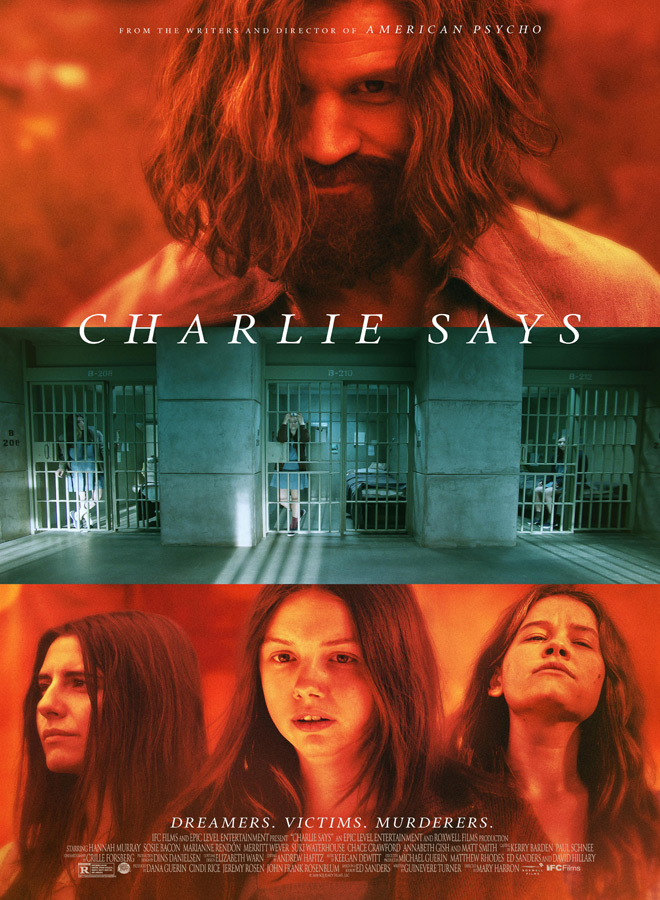

Faith even detailed her story in a book – The Long Prison Journey of Leslie Van Houten. Both this book, and The Family by Ed Sanders, were combined into a screenplay by Guinevere Turner (Preaching to the Perverted 1997, The Notorious Bettie Page 2005) for the new film Charlie Says. Making its debut at the 75th Venice Film Festival last year, it will be released in select theaters on May 10th through IFC Films.

Directed by Mary Harron (I Shot Andy Warhol 1996, American Psycho 2000), it tells the story of how Van Houten (Hannah Murray: Skins series, Game of Thrones series), Krenwinkel (Sosie Bacon: Off Season 2015), and Atkins (Marianne Rendón: Mapplethorpe 2018) ended up with Manson (Matt Smith: Doctor Who series), and how Faith (Merritt Wever: Birdman 2014) reached out to them.

It certainly promises something unique – a Charles Manson flick about his flock. Most pieces of media talk about the man himself rather than the minions. Does that make it good though? Is the film worth sticking out for its 1 hour and 50-minute run-time?

That is not to say Manson is not there. He just is not the central figure. The film is not about getting into his head but getting him out of the heads of others. His appearances come in the form of flashbacks, taken from Murray, Bacon and Rendón’s characters relating their stories to Wever’s Faith. It makes it a straightforward way of intersecting the elements from Sanders’ book into Faith’s own story. Still, it gets the message across; the women think Manson is the bee’s knees, and explain why, not able to see how screwed up it was until later.

Faith is introduced to them similarly to Clarice meeting Hannibal Lector in 1991’s Silence of the Lambs; sitting on a chair in front of them as they stand behind bars over her. Their behavior is always slightly off, giving off a worrying vibe. Yet, once they start telling their story, one gets the sense that, as Faith says, “Maybe they’re victims too.” Then maybe Faith’s course of women’s studies could start them on the path to healing.

It sounds engaging enough when it is put that way. The jail scenes between Wever, Murray, Bacon, and Rendón come off the strongest. Wever’s Faith gradually confronts them with the truth about Manson’s rhetoric. Murray, Bacon, and Rendón do well as the starry-eyed flock, though the best performance would have to go to Wever, putting in an earnest job as a woman driven to deliver an unenviable task.

The flaws come mostly in the flashbacks. When the women start talking or reminiscing, the film shifts back to those sun-kissed, ’60s summers at the Ranch. One would think it would show the women’s gradual fall to Manson’s spell, just as Faith’s scenes show their rise out of it. Except they are either already into the family or fall for Manson all too quickly. The film does not show why they joined or why they stayed. There is the suggestion they were looking for love, yet the film does not show Manson as a ‘lovable’ option.

Smith’s Manson certainly gives it his all, going all-in on being a creepy cult leader. He babbles wildly, delving into sexism and racism while trying to pass himself off as a visionary. All in all, the film shows Manson for what he was; a monstrous, little creep. So why would it take multiple classes in women’s studies for Van Houten et al to see that? One could say these classes are causing them to reflect on their memories without the scales on their eyes. It is just that the audience does not see the scales form on them to begin with.

In turn, this reflects badly on the women. The film shows them as being strung along on Manson’s path, while also showing Manson as a failed musician with twisted ideas. The film does not want to 100% blame the women for the murders, while also not risking glorifying Manson by making him a powerful figure. So, it ends up taking an awkward stance; Van Houten and company either had little to no will of their own to begin with or agreed with his talk from the start.

Still, it is at least putting the women at the forefront, considering their story than making them the middlemen between Manson and the knife. It is technically sound too. The cinematography is particularly impressive, contrasting the greyish-blue jail scenes with the sunny days at the ranch, which contrast in turn with the drama.

If the structure was tighter, taking a stronger stance with Manson for the women’s benefit, Charlie Says could have been a more powerful Drama. Instead, it is just a fair go at an angle that is rarely covered. As such, Cryptic Rock gives this film 3 out of 5 stars.

No comment